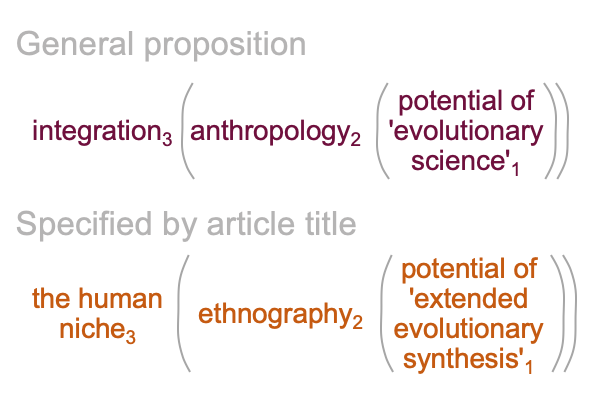

Looking at Augustin Fuentes’s Article (2016) “The Extended Evolutionary Synthesis…” (Part 8 of 16)

0084 Descent with modification is the name of the evolutionary game, according to Darwin.

Darwin assumes some process of inheritance that yields variety in each generation. This is accomplished by mixing chromosomes from the male and the female in sexual reproduction. So, variation is assured with descent. Every member of a species has a different phenotype (and sometimes, those differences cannot be easily observed).

Modification comes by way of natural selection. Adaptations are modifications that increase reproductive success (what used to be called “fitness”). Reproductive success is the likelihood of one’s descendants surviving to… um… reproduce.

0085 The confusion?

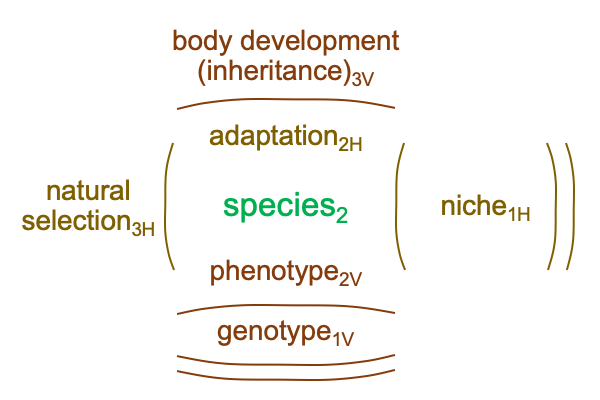

A phenotype2b is not the same as an adaptation2b. However, they both refer to same entity: a species. A “species” is a Latin term that can mean an individual, a kind, or a type. So, “species” can denote an individual, a species or a genus.

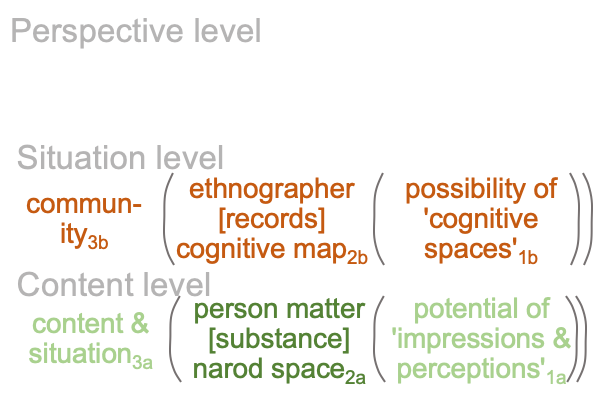

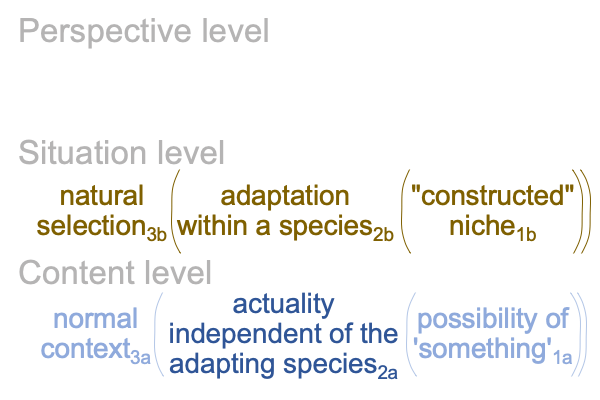

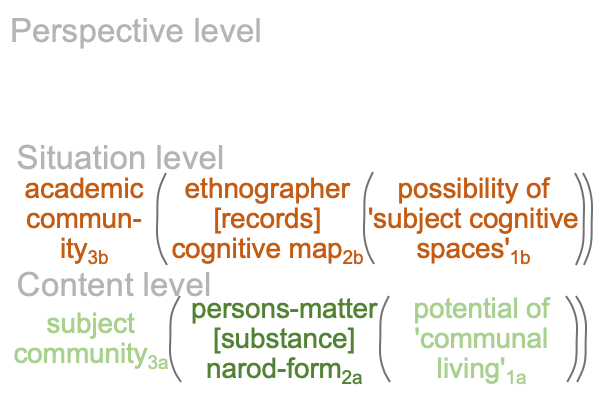

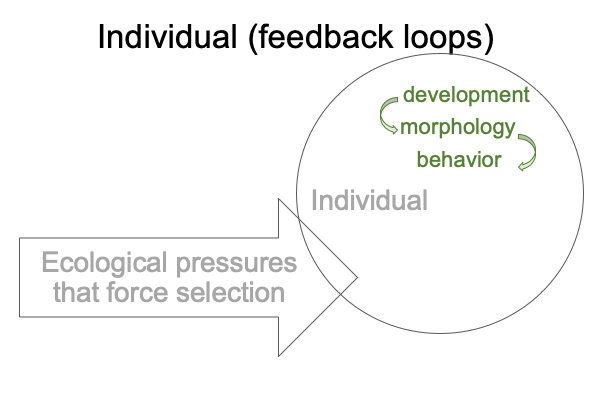

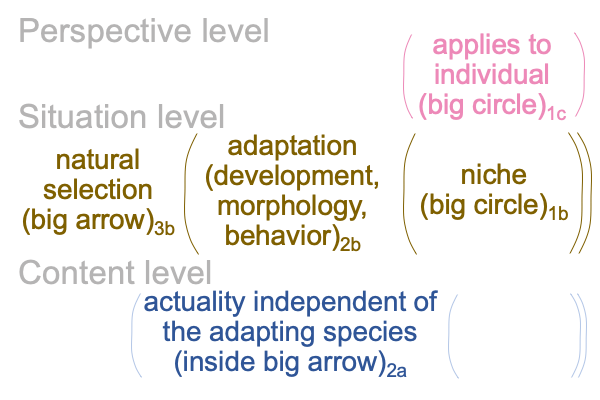

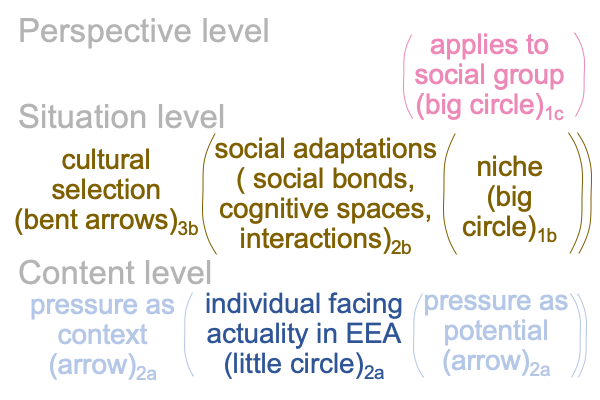

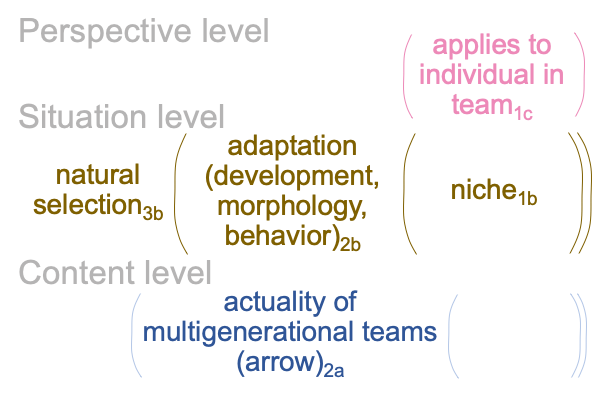

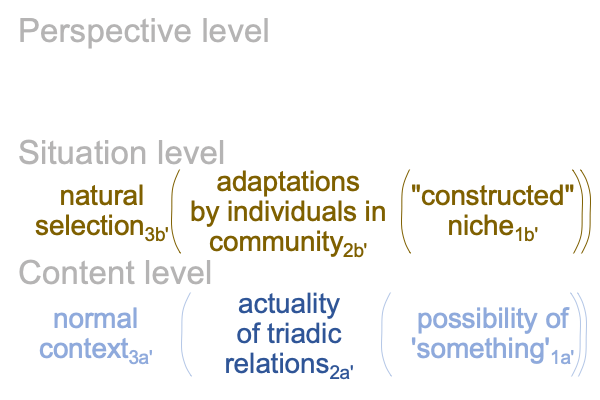

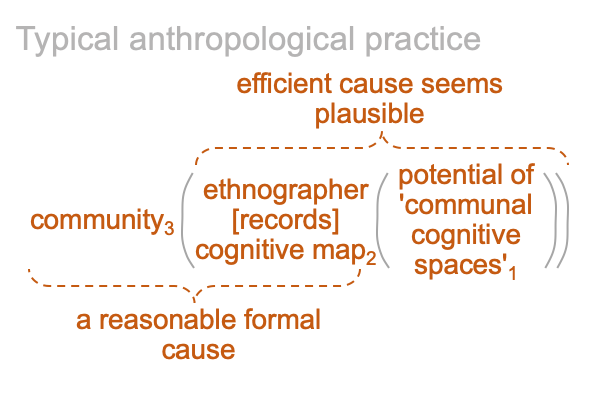

0086 Here is a picture of this double referral. The structure is called an “intersection”.

Two category-based nested forms intersect.

0087 An adaptation2H refers to a species2 within the normal context of natural selection3H operating on a niche2H. Note how the actuality independent of the adapting species gets shoved under the rug.

A phenotype2V refers to a species2 within the normal context of body development3V operating on a genotype1V. Here, DNA gets pulled offstage.

0088 Here is the confusion.

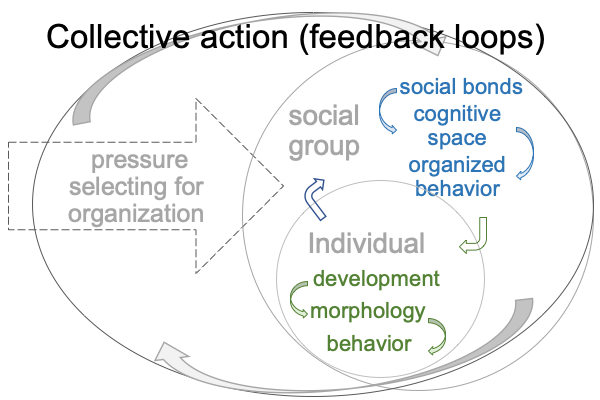

If one proceeds with an explanation in natural history, such as the theory of niche construction, the horizontal axis is active. Nevertheless, the horizontal axis intersects the vertical axis. So, research into a genetic explanation is called for in each instance of adaptation into a constructed niche.

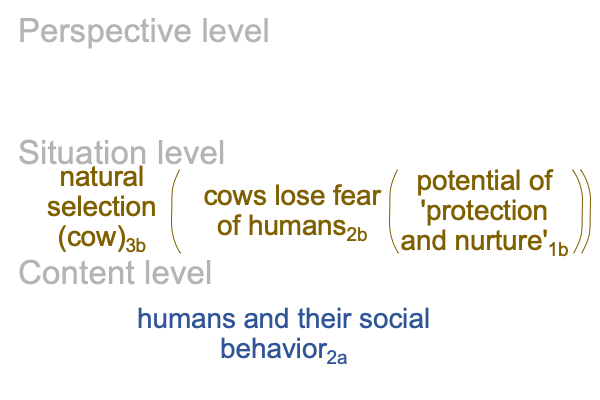

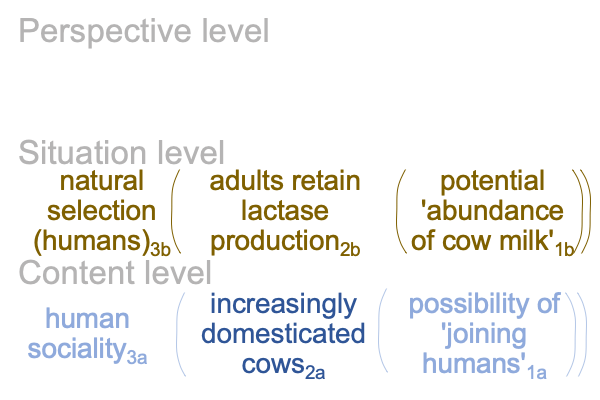

0089 For example, for the co-evolution of cows and humans. Cows adapt to human sociality (by becoming domesticated). Humans adapt to cow milk as food, even in adulthood (by becoming lactose-tolerant). Adaptation2Hintersects with phenotype2V. So an inquiry into body development3V and genotype1V is demanded for a full explanation of both cow and human adaptations. However, body development3V is not a cause for adaptations2H, natural selection3H is.

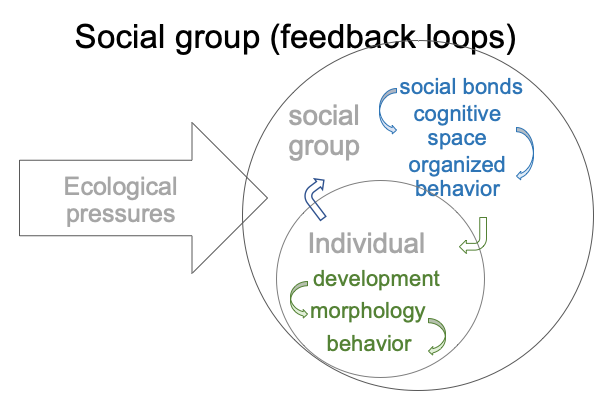

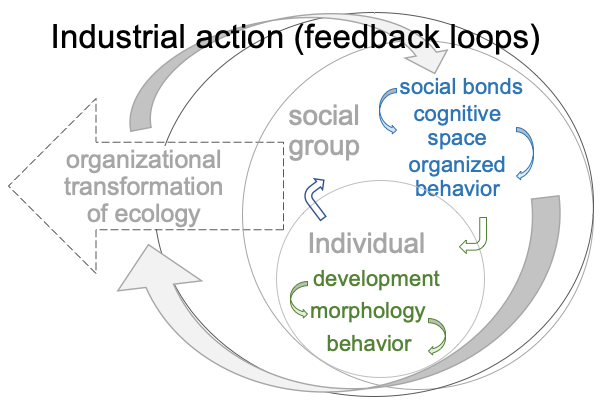

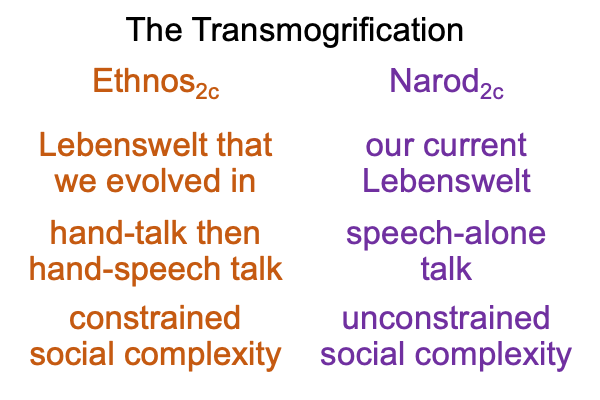

0090 To me, natural history and genetic explanations are often confused, so much so that the author claims that human activity affects genetic and other biological patterns. Plus, natural selection can influence developmental outcomes, which in turn feed back into human activities.

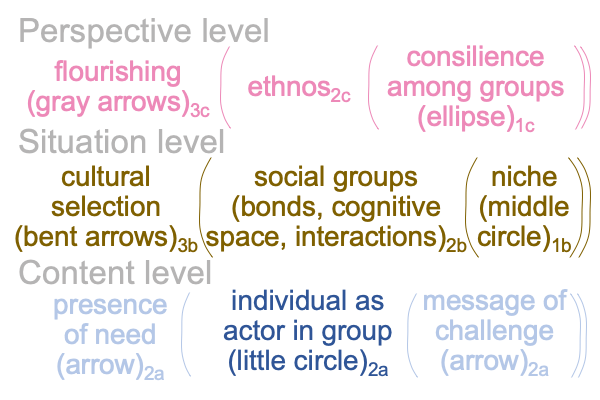

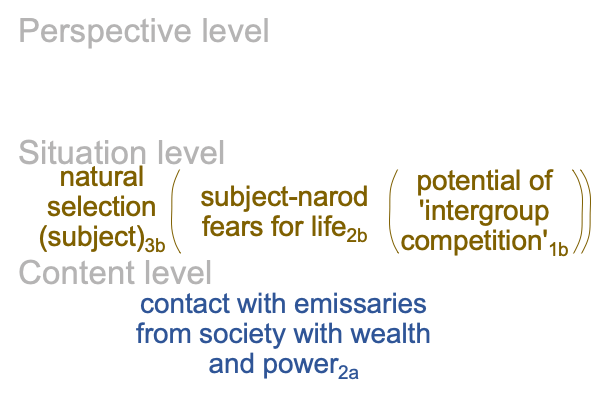

0091 To me, the process of ‘niche construction’ is intelligible, not because the extended evolutionary synthesis permits natural history to intersect with genetics, but because niche construction extends the actuality independent of the adapting species2a by introducing an adaptation-induced normal context3a and potential1a.

Yes, an induced normal context3a and potential1a can change the character of the actuality2a that is theoretically independent of the adapting species.

0092 In the case of the cow2a, the animal2a becomes domesticated.

In the case of the human2a, the human2a becomes entangled.

In 2012, Ian Hodder writes a book titled Entangled: An Archaeology of the Relationships between Humans and Things(Wiley and Blackwell, Oxford).

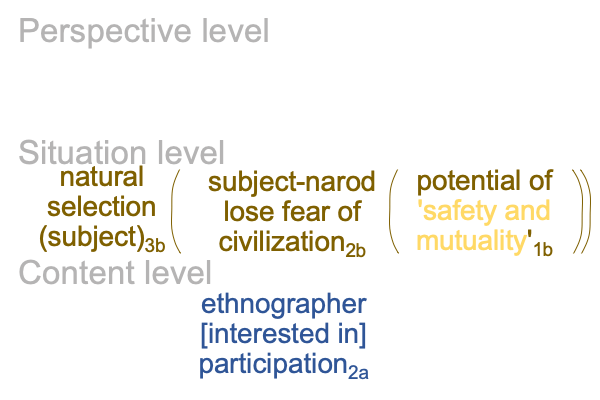

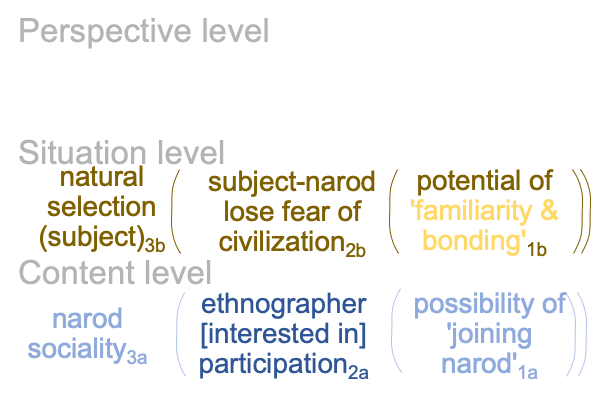

0093 To me, the author avoids the entanglement aspect, even though it awaits the unsuspecting anthropologist.

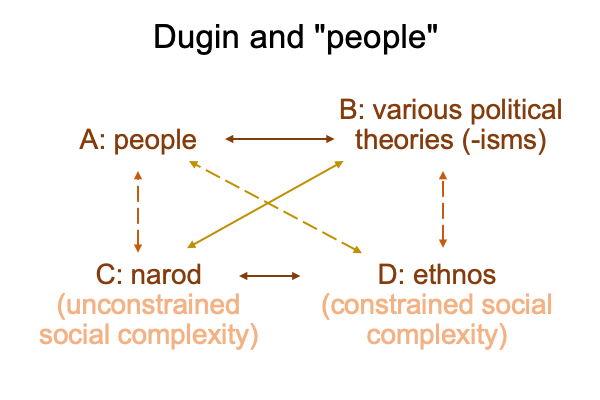

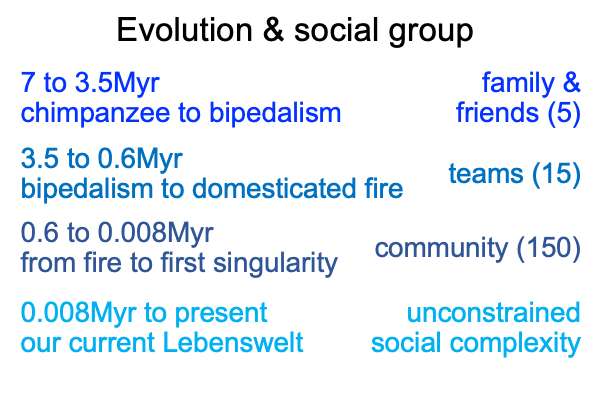

Furthermore, the author of the article under examination suggests that the niche-construction approach, for humans, may illuminate cultural complexity.