Looking at Alex Jones’s Book (2022) “The Great Reset” (Part 9 of 12)

0102 Here is where I left off in the last blog.

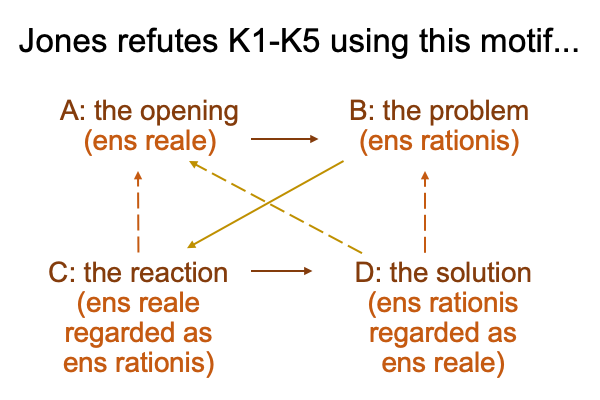

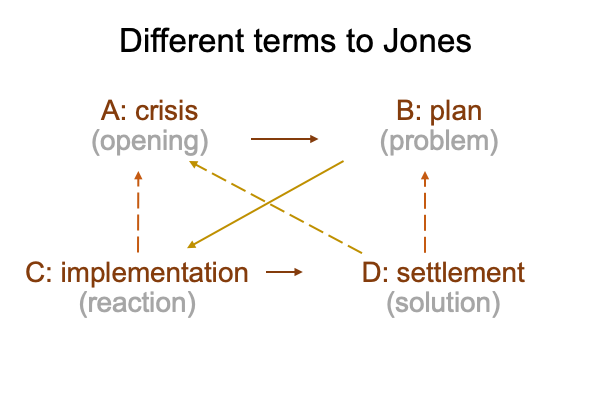

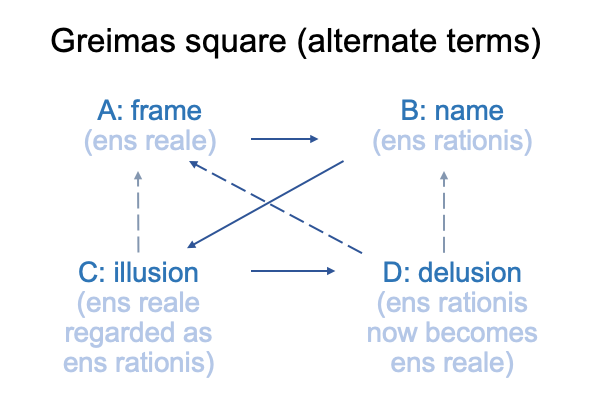

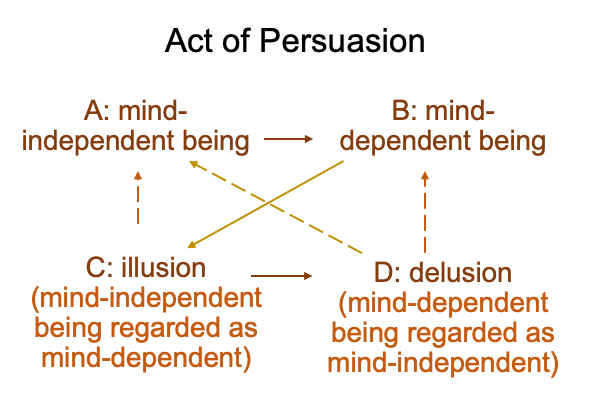

0103 Another author with the name of Jones, describes the act of persuasion as applying a category of the mind.

To start, there is the mind-independent reality of a situation (A).

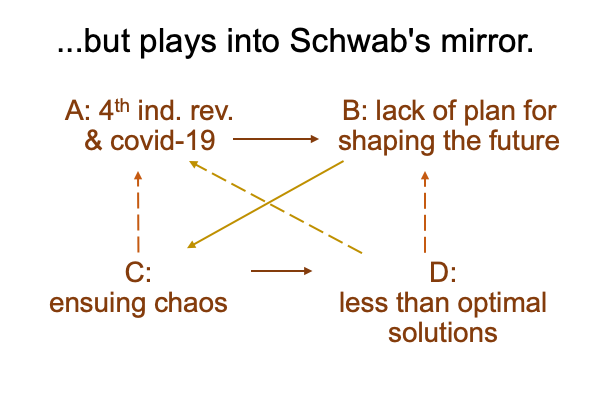

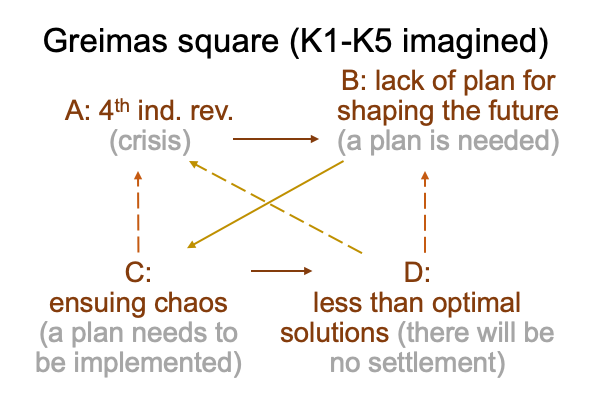

For Schwab, this mind-independent reality includes thousands of people working independently, as well as collaboratively, in cutting edge technologies, including artificial intelligence, robotics, material science, genetic research, biochemistry, biology and so on. All these technologies will contribute to shaping the future in ways that those who seek control cannot control. Those who seek control envision chaos.

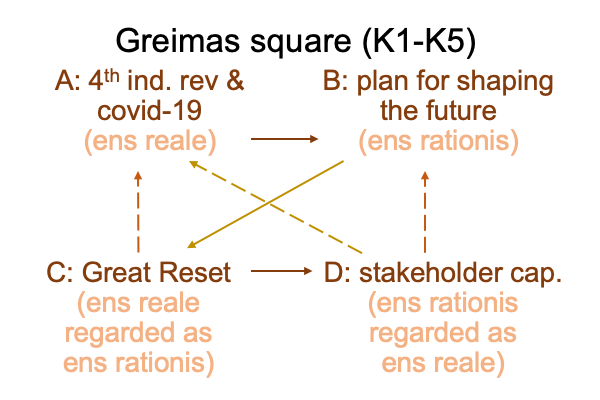

0104 So, B, a mind-dependent being, is formulated. As per the rules of the Greimas square, B contrasts with A and sets the stage for a creative leap to an apparently mind-dependent being, C.

For Schwab, this mind-dependent being (B) is a plan for shaping the future, courtesy of the World Economic Forum, composed (according to Jones) by those who seek control (or their representatives and lackeys, who are compromised and therefore easily… um… directed.)

0105 The mind-dependent being (B) represents the mind, in the term, category of the mind.

How so?

Well, the mind (B) engages what itB thinks belongs to the outside world (A), that is, mind-independent being, as if itA (A) is a mind-dependent being (C).

For example, if I find a slab of marble (A), and I figure that I can carve a statue of ‘something’ (B), I begin chiseling (C) this mind-independent being (A) according to my vision (B). This artisanal example is not only a creative act, but it exhibits the purely relational character of an act of persuasion.

0106 As the slab of marble is fashioned (C) it speaks against the ‘something’ that I figure I can carve (B). Plus, itCcomplements the integrity of the originating thing (A).

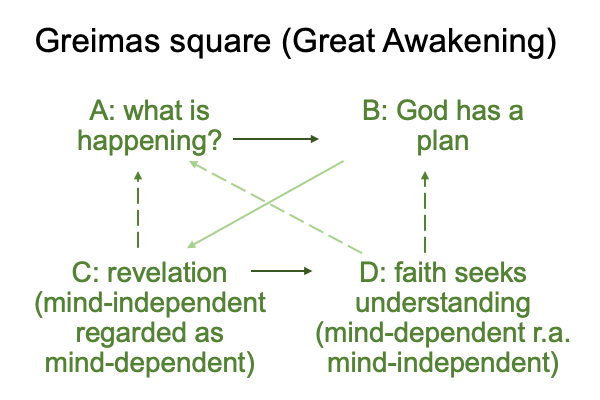

For Schwab, the fashioning of the fourth industrial revolution (including the covid-19 business) (B) is precisely an artistic effort (C), similar to a sculptor working on stone. However, as Jones rightly notes, the metaphorical slab of stone is composed of humans, who can be as dumb as bricks, but nevertheless bear the image of their Creator.

Who is the creator here, God or the sculptor of the Great Reset?

Illusions (C) can be confounding. To the mind, a mind-independent being takes on the character of mind-dependence.

0107 Next comes a delusion (D), a mind-dependent being that is categorized as mind-independent.

Ah, is D the category-aspect of the term, “category of the mind”?

Yes, the other Jones is onto ‘something’.

If D goes with “category” and B associates to “of the mind”, then the other Jones’s term, “category of the mind”, labels how D complements B, contrasts with C, and speaks against A.

0108 A delusion (D), appearing to be mind-independent, applies a category of the mind onto the originally mind-independent topic (A).

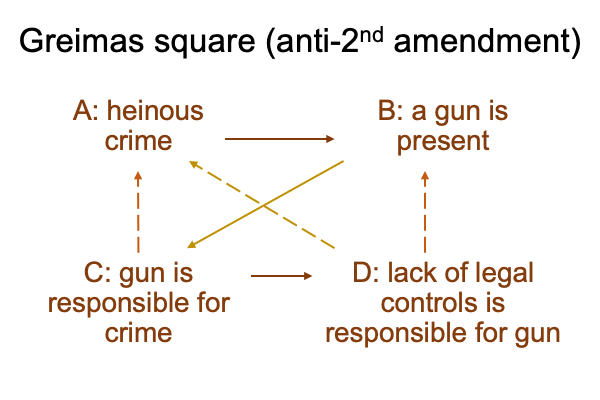

For the first example of an act of persuasion discussed in these blogs, the apparently mind-independent being is the second amendment of the Constitution (D). This category of the mind is superimposed, by corporate media, upon heinous crimes (A).

0109 The delusion (D) expresses a mind-independent being that speaks against the originating mind-independent being(A).

Thus, the delusion (D) imposes a category of the mind onto the originating focus (A). It is as if the second amendment(an apparently mind-independent being) opens the door to heinous crimes (as mind-independent beings) and is therefore complicit. If this statement makes sense, then pause and savor the delusion (D) as an act of persuasion, leading to the imposition of a category of the mind upon mind-independent being.

0110 Both D and B precipitate, or “co-create”, the category of the mind.

The delusion (D) complements the mind-dependent being (B) and, often enough, serves as a mental impression of the originating mind-independent being (A). B is the mind in a category of the mind. D is the category.

Who is the other Jones?

Think E. Michael.

0111 For Schwab, the delusion (D) comes with the label, “stakeholder capitalism”. Stakeholder capitalism is like a statue, a mind-independent being, chiseled out of social upheaval during the fourth industrial revolution. There are three stakeholders: progress, people and planet. All three are reified into mind-independent beings that somehow put capital, the undead blood flowing through the living arteries and veins of the global economy, into perspective.

Once the work of the Great Reset (C) is complete, stakeholder capitalism (D) will have replaced the second amendment (D) as the mind-independent being (D) imposed on all sorts of encounters with reality (A).

Schwab’s act of persuasion will become fiat accompli.

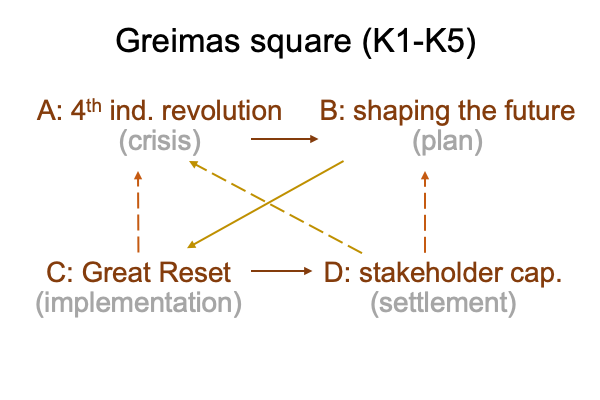

0112 Here is a diagram of the Greimas square derived from the titles of Klaus Schwab’s five books.