Looking at N. J. Enfield’s Book (2022) “Language vs. Reality” (Part 1 of 23)

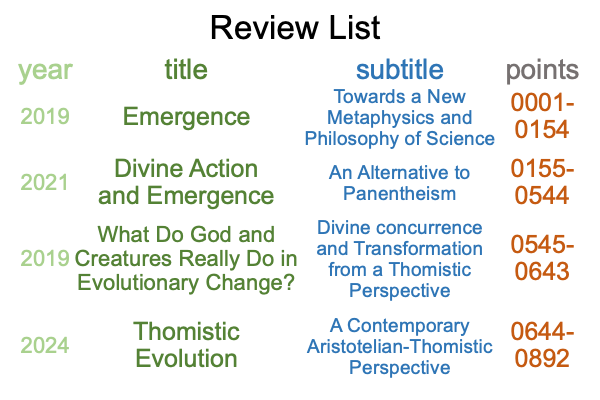

0841 This is an encore performance to the sequence of blogs on the post-truth condition.

As such, this examination wraps up Part Two of Original Sin and the Post-Truth Condition (available at smashwords and other e-book venues).

Take a gander at the full title of Enfield’s text, Language vs. Reality: Why Language Is Good For Lawyers and Bad For Scientists.

Surely, that sounds like a book that belongs to a set of books on the post-truth condition.

So, the numbers continue to build from the last examination.

0842 The book is published by MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

The author is a professor of linguistics at the University of Sydney and the Director of the Sydney Centre for Language Research.

0843 The title of the book is a play on John B. Carroll’s (editor) collection of essays by Benjamin Lee Whorf (1897-1941 AD), published in 1956 under the title, Language, Thought and Reality.

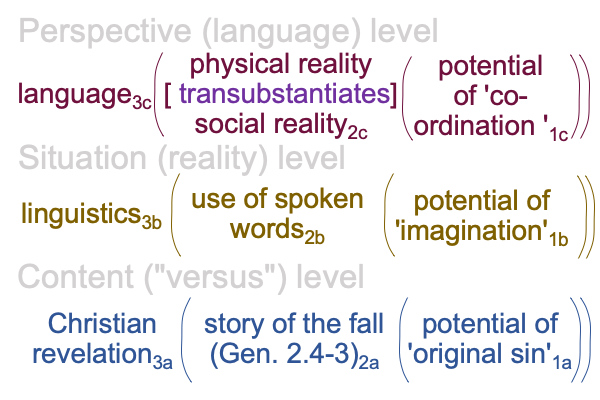

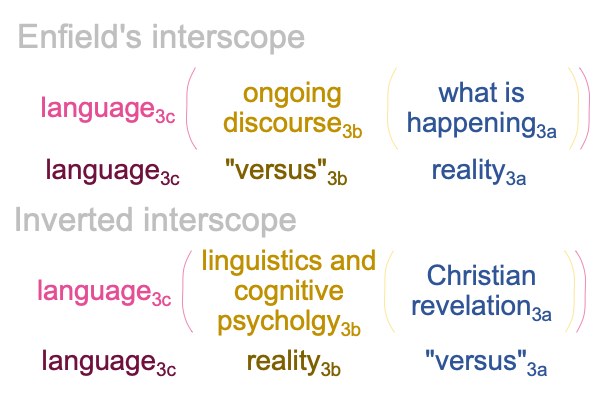

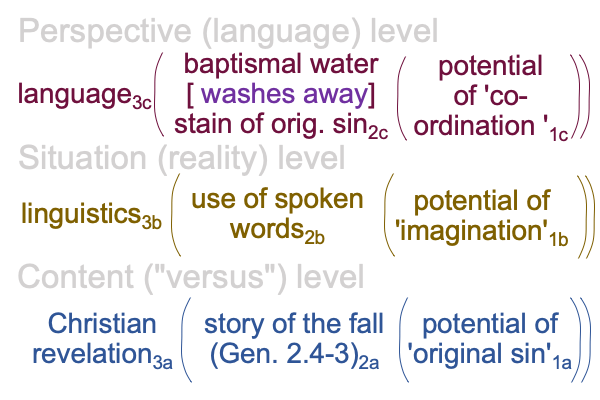

To me, this implies that “thought” has transubstantiated into “versus”. The substance of the word has changed, so to speak. The word, “versus”, derives from the same root as the word, “adversary”. So, if “thought” once used to nominally stand between “language” and “reality”, then today, “thought” is confounded with “adversary”, and that might serve as a hint concerning the nature of our adversity.

Perhaps, this is not the only notable feature of the title.

Then again, a book titled, Language, Adversary and Reality, might not fly off the shelves in feel-good book-outlets. It is not as if, next to the Self-Help section, there is a Come To Grips With Your Doom section.

So, expect me to play with the title throughout this examination.

0844 Another notable feature of this book, at least to me, is that the author is not acquainted with Razie Mah’s re-articulation of human evolution, in three masterworks, The Human Niche, An Archaeology of the Fall and How To Define the Word “Religion” (available at smashwords and other e-book venues). The evolution of talk is not the same as the evolution of language. Language evolves in the milieu of hand talk. Plus, the evolution of talk comes with the twist, humorously called, “the first singularity”.

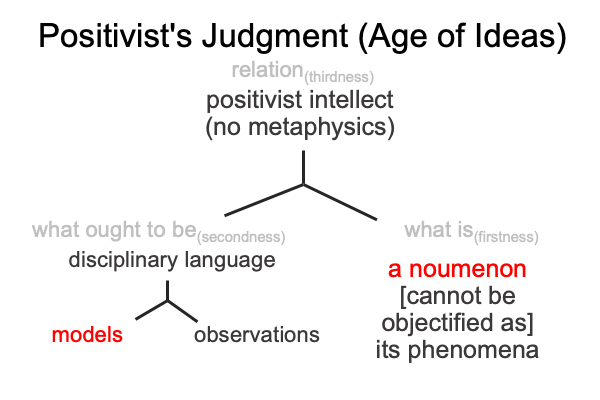

So, Enfield’s work serves as a marker for the twilight of the Age of Ideas and the dawning of the Age of Triadic Relations.

0845 Okay, let me dwell on the idea that the evolution of language is not the same as the evolution of talk.

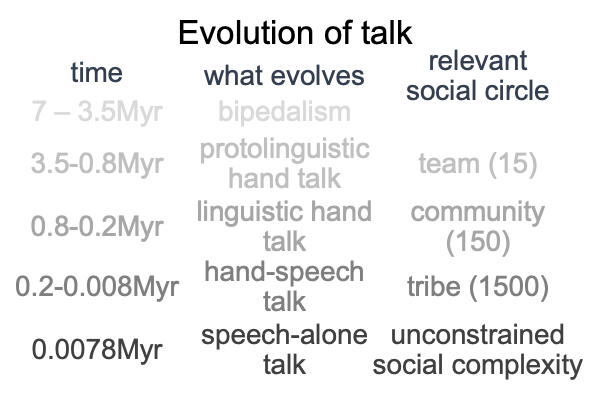

Comments on Michael Tomasello’s Arc of Inquiry (1999-2019) (by Razie Mah, available at smashwords and other e-book venues, and also, for the most part, appearing in Razie Mah’s blog for January, February and March, 2024) divides the evolution of talk in the following manner.

0846 The first period starts with the divergence of the chimpanzee and human lineage (7 million of years ago) and ends with the bipedalism of the so-called “southern apes” (around 3.5 to 4 million years ago).

In the second period, australopithecines adapt to mixed forest and savannah by adopting the strategy of obligate collaborative foraging. Eventually, Homo erectus figures out the controlled use of fire, leading to the domestication of fire, starting (perhaps) around 800 thousand years ago.

The third period, lasts from the domestication of fire to the earliest appearance of anatomically modern humans. During this period, hand talk becomes fully linguistic, religion evolves as an adaptation to large social circles (of 150 individuals and more) and hominins use the voice for synchronization during seasonal mega-band and occasional tribal gatherings. Then, sexual selection does the rest and the voice comes under voluntary neural control.

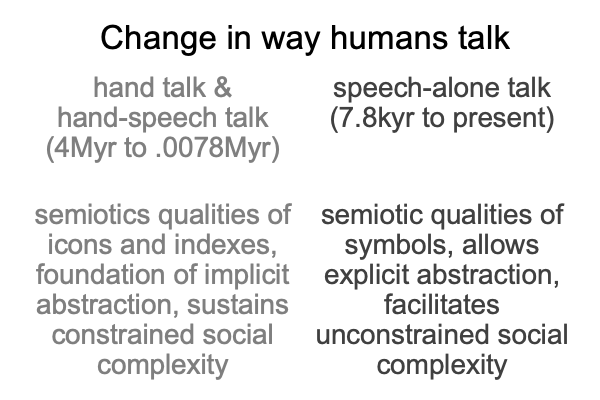

0847 The fourth period starts when the voice, now under voluntary control, joins hand-talk, resulting in a dual-mode way of talking, hand-speech talk. Hand talk retains the iconicity and indexality that grounds reference in things that can be pictured or pointed to. But, speech adds a symbolic adornment, which starts as a sing-along and ends up taking a life of its own. Four centuries ago, the North American Plains Indians and the Australian aborigines still practiced hand-speech talk, with full fledged sign and verbal languages. Now, their hand-speech talk is all but dead.

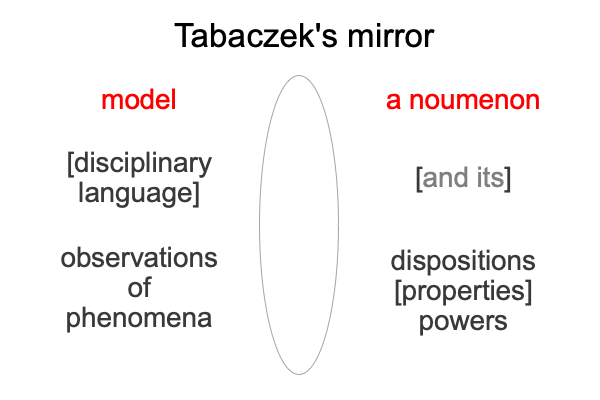

0848 That death, along with the demise of all hand-speech talking languages, comes (and came) due to exposure to speech-alone talk, which has significantly different semiotic qualities than hand-talk and hand-speech talk. Hand-talk is iconic and indexal. The referent precedes the gestural word. Speech-alone talk is purely symbolic. The spoken word labels ‘something’, and sometimes that ‘something’ cannot be imaged or indicated.

Well, it must be real because speech-alone talk provides a label for an explicit abstraction!

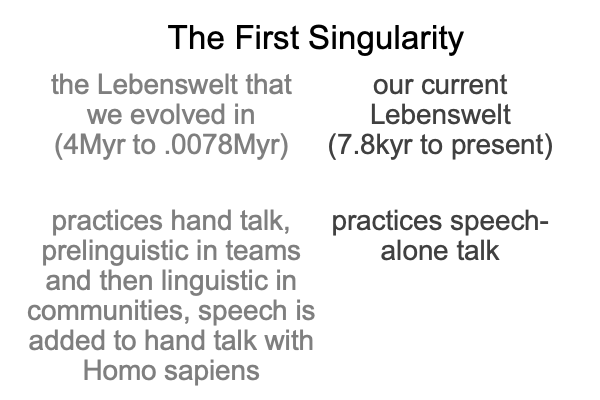

0849 Here is a picture of the transition labeled, “the first singularity”.

0850 Consider the words, “language”, “adversary” and “reality”. Each word is a label for ‘something’ that cannot be pictured or pointed to. These words do not exist in hand-talk or hand-speech talk, because the referent cannot be imaged or indicated using a manual-brachial gesture. What does this imply? Does a referent exist because a label has been attached to it? Or, does an explicit abstraction properly label referents that exist irrespective of the spoken word? This type of question is addressed in Razie Mah’s masterwork, How To Define The Word “Religion”.

Fortunately, the author of the book under examination is unaware of the first singularity and the difficulties that a change in the way that humans talk poses. Human evolution comes with a twist.

0851 So why examine this work?

Well, I expect to see the evolution of talk manifesting in this book, even though the author is not aware of Razie Mah’s academic labors.

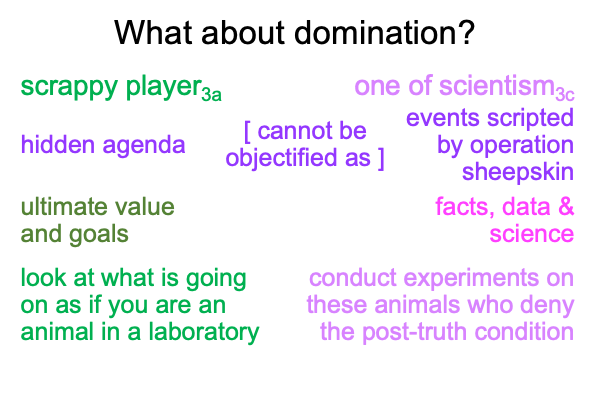

Surely, Enfield’s work details recent scientific research in linguistics and cognitive psychology, in an attempt to provide the reader with a coherent view of how language is good for lying lawyers and bad for honest scientists.

What will this examination reveal?