Looking at Daniel Dennett’s Book (2017) “From Bacteria To Bach and Back” (Part 18 of 20)

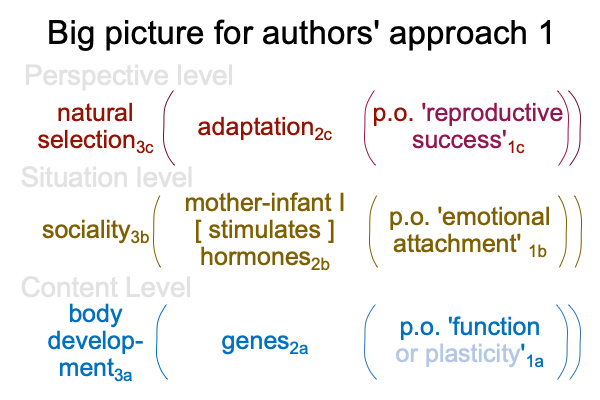

0183 If human culture is to be modeled as the replicative success of memes, then what would empirio-schematic researchentail?

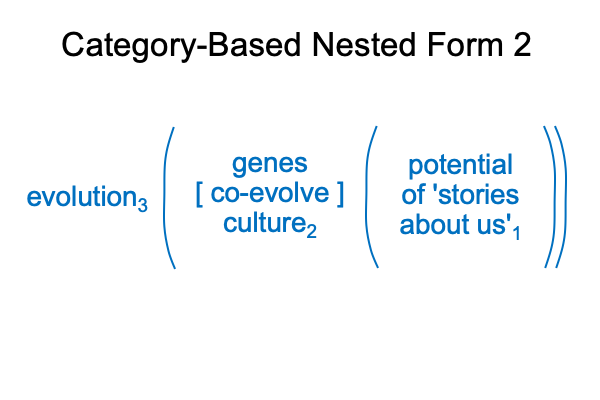

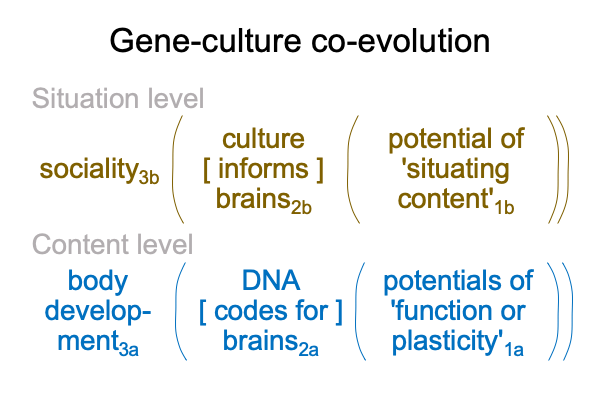

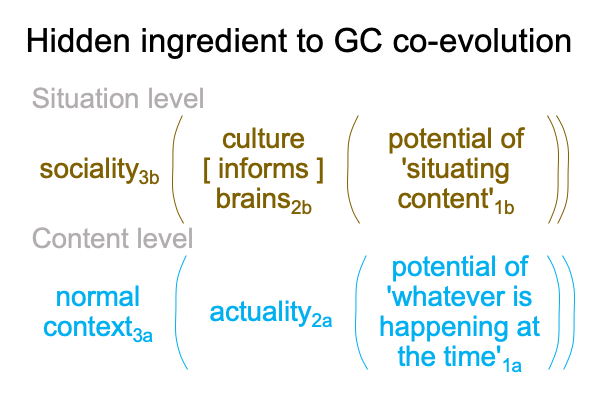

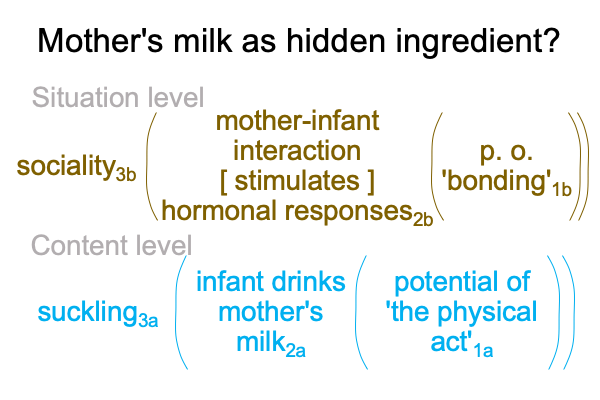

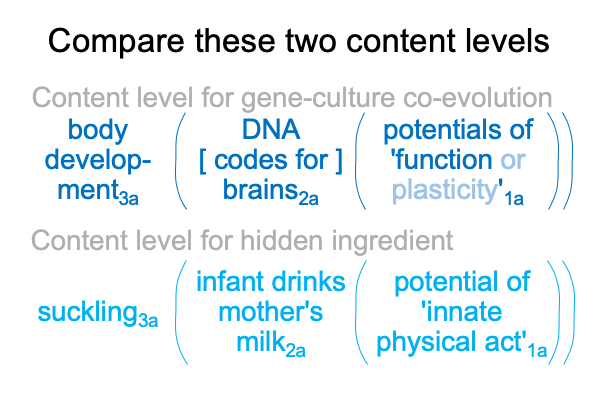

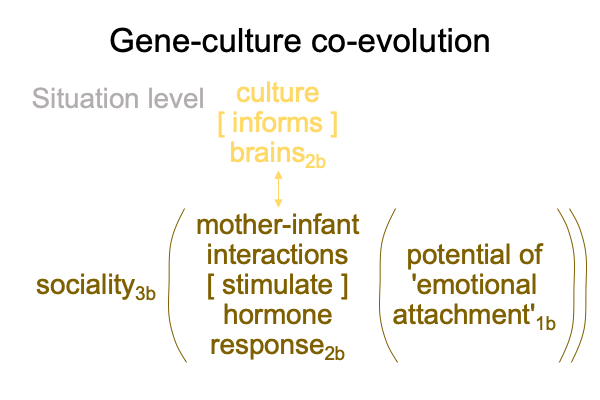

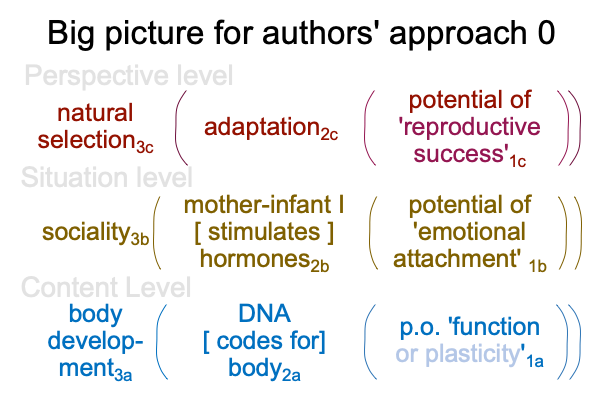

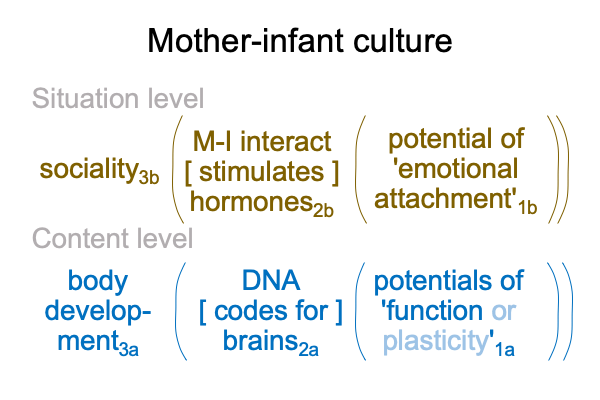

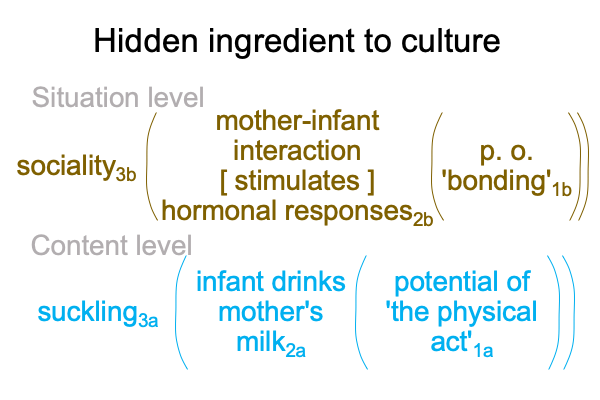

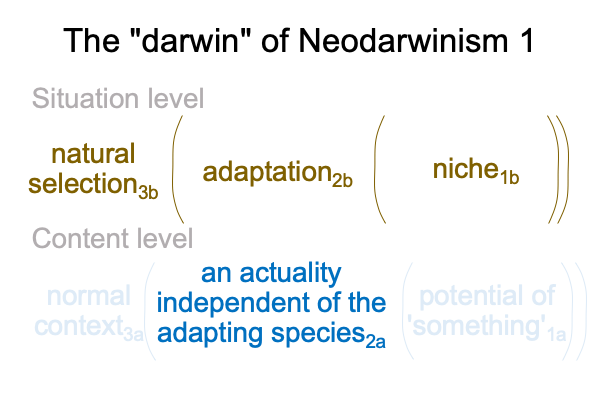

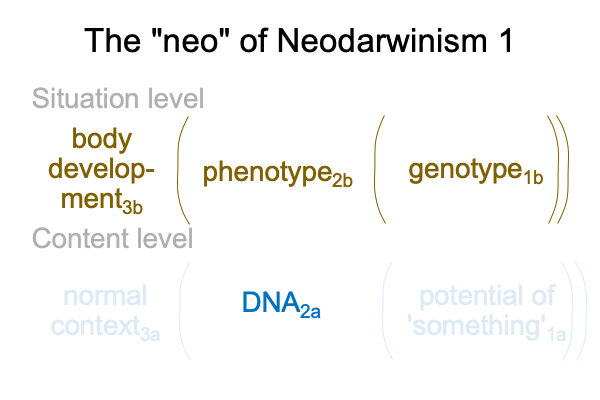

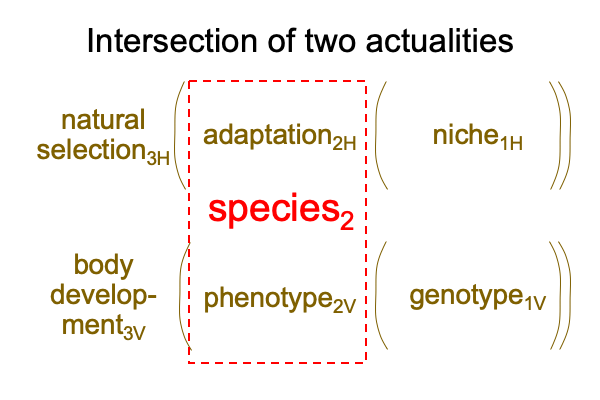

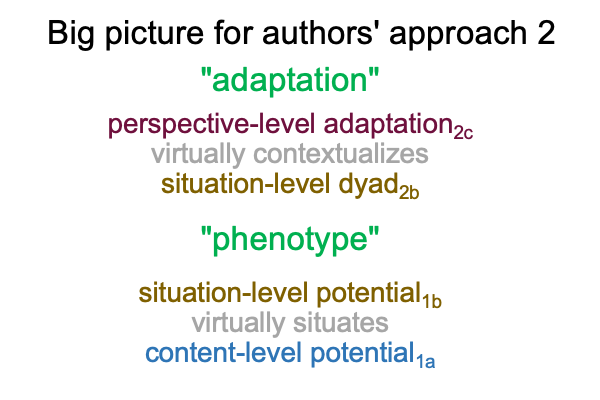

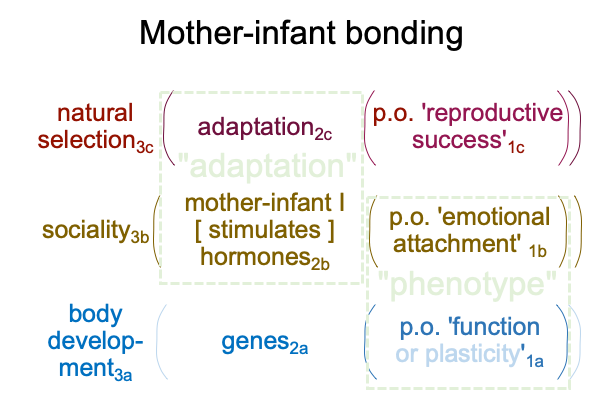

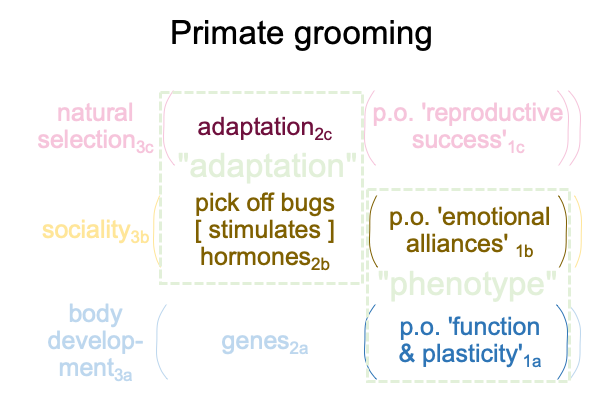

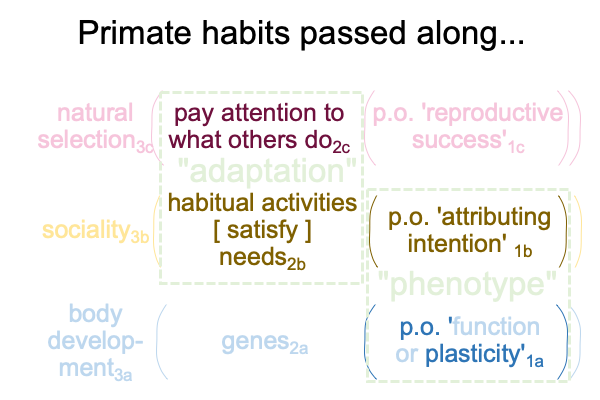

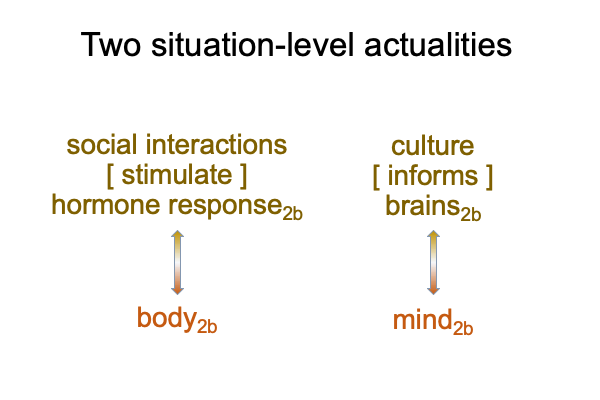

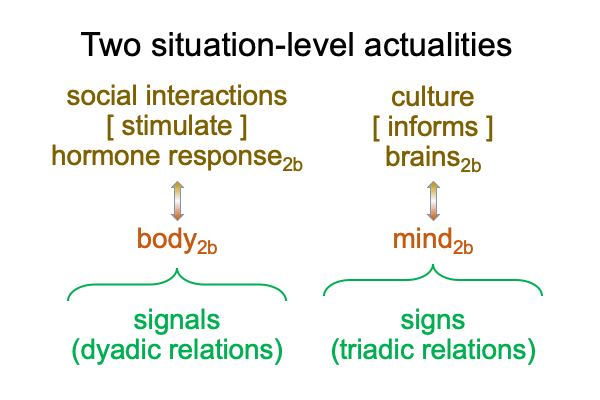

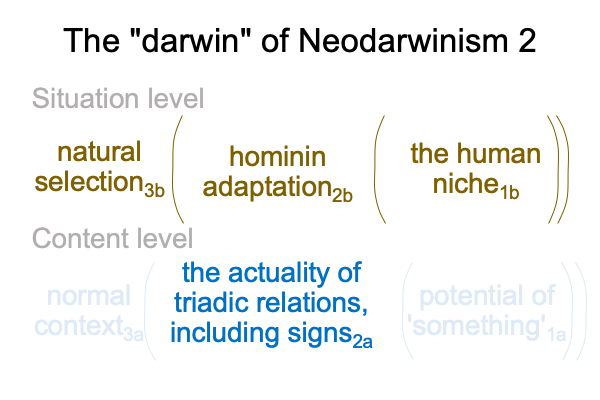

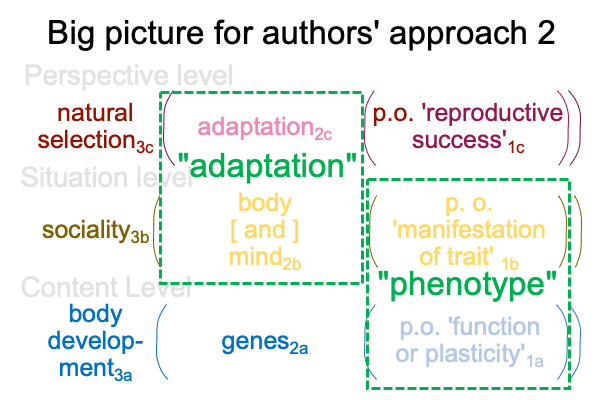

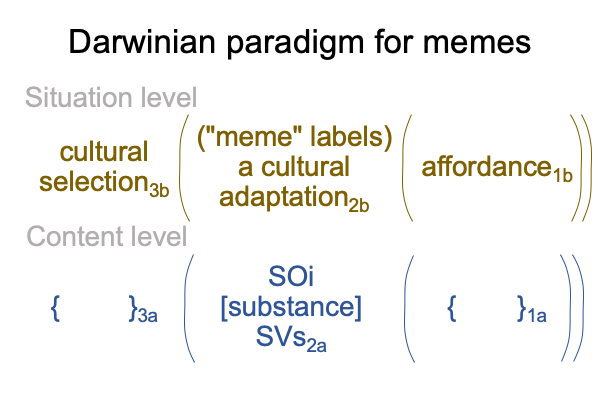

Well, if the term, “meme”, labels a cultural adaptation2b, in the normal context of cultural selection3b operating on various affordances1b, then the actuality independent of the adapting species2a must relate to the scholastic interscope of how humans think2a.

Indeed, I may highlight one particular element in the scholastic interscope2a, the species impressa2a, as the premier feature of the actuality independent of the adapting species2a.

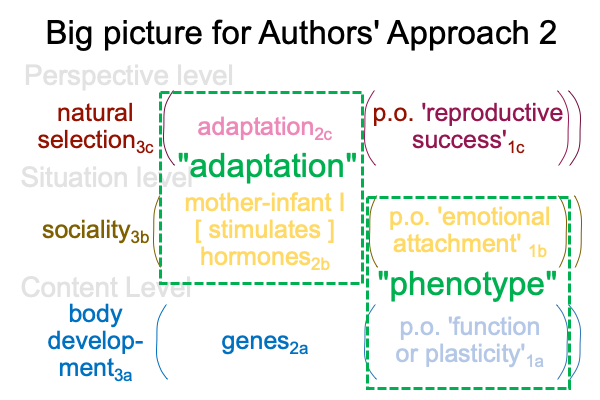

0184 But, didn’t I offer the above content-level actuality2a as a technical definition for the term, “meme”?

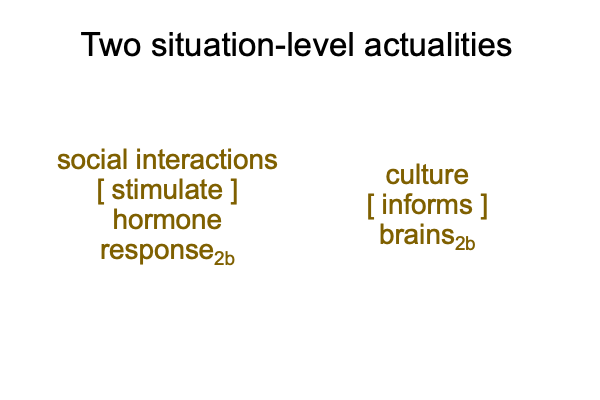

So, how can the term, “meme”, also stand for a situationb-level actuality2 in the normal context of cultural selection3b?

If that is not confusing enough, consider that the content-level actuality2a also belongs to the manifest image (which is described by all three actualities of the scholastic interscope).

Plus, we are conscious of a manifest image, not its scientific image.

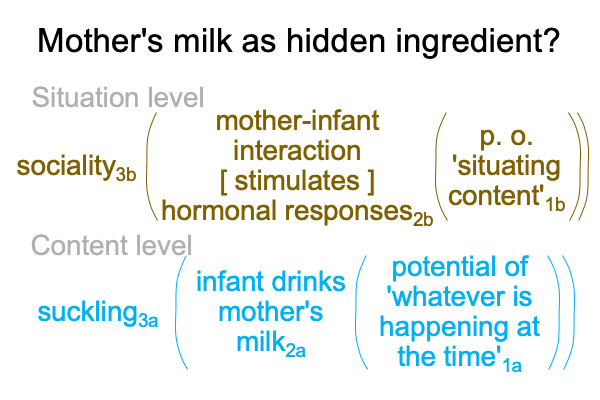

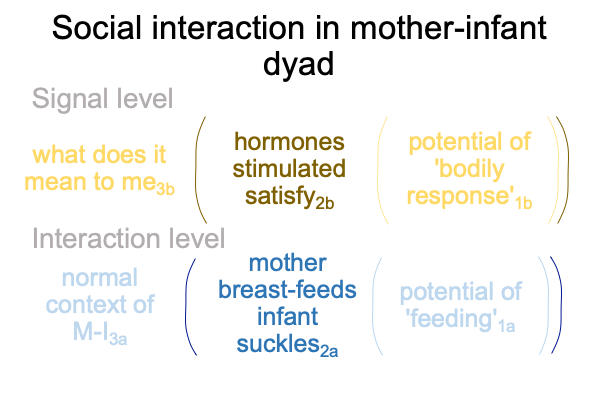

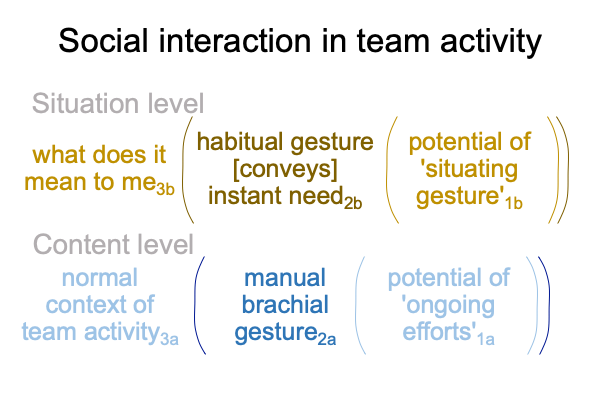

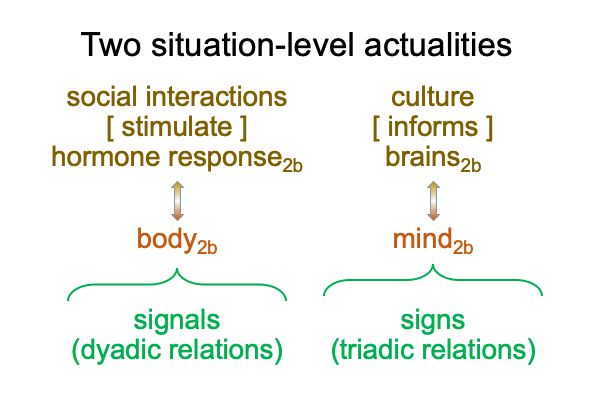

0185 Consciousness is the user-illusion of competition among neurons for active synapses3b. Synaptic networks form and are maintained in response to memes. The qualia that we feel are most likely memes, sign-objects of interventional signs substantiating sign-vehicles of specifying signs.

Consequently, another term for [substance] is [implicit abstraction]. The sign-objects of interventional signs (SOi) are like matter. The sign-vehicles of specifying signs (SVs) are like form.

So, a meme may be denoted as SOi [implicit abstraction] SVs.

0186 Another word for [substance] might be, “projection”.

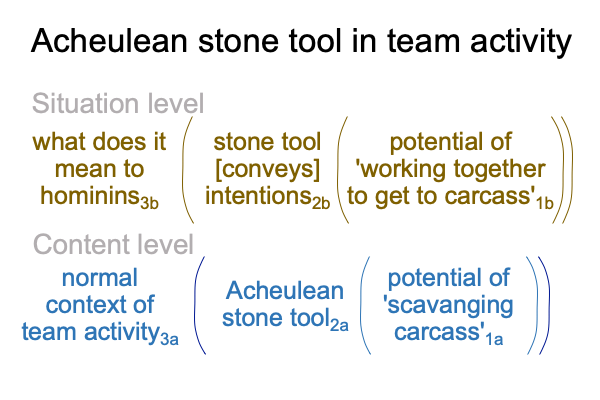

In projection, the situation-level potential1b projects continuity into the content-level contiguity.

For example, there is no motion in cinema. There is only a rapid sequence of images cast upon a screen. The user illusion projects (or implicitly abstracts) smooth motion in time. This is only possible if the situation allows it.

Similarly, there is no sweetness to the fact that the neighbor’s cat is dead. There is only a corpse in the refrigerator and Daisy’s querying gaze, asking, “When are you going to give the dead cat back to me?”

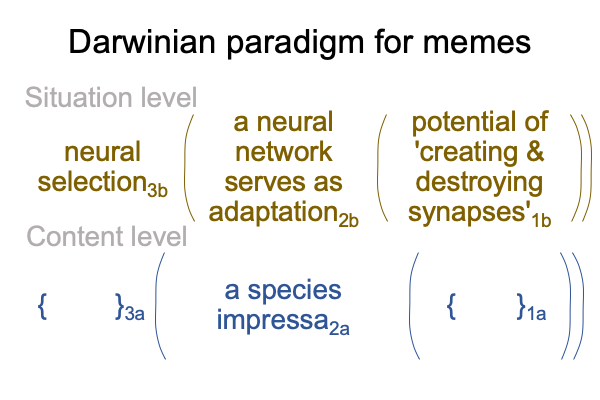

So, the term, “meme”, also labels a neural network2b, in the normal context of neural selection3b operating on the potential of creating and destroying synapses1b, in the process of situating a species impressa2a.

But, once again, didn’t I offer the above content-level actuality2a as a technical definition for the term, “meme”?

Yes, but neural networks are clearly implicated, since they constitute the adaptation2b, and the adaptation is um… what?… a meme?

0187 If that is not enough, the designs of the most intelligent human designer cannot be compared to the adaptivity that arises from a variation of Darwinian natural selection operating on units of culture, in all their varieties. Why? There is always a cultural… er… cognitive space that even the most neurotic and attentive-to-detail engineer cannot plan for.

Consequently, cultural selection3b yields memes that survive and flourish on their own and some of these memes are so strange and resilient that they appear miraculous, even to the positivist intellect. Therefore, they must be ruled out as “not scientific”.

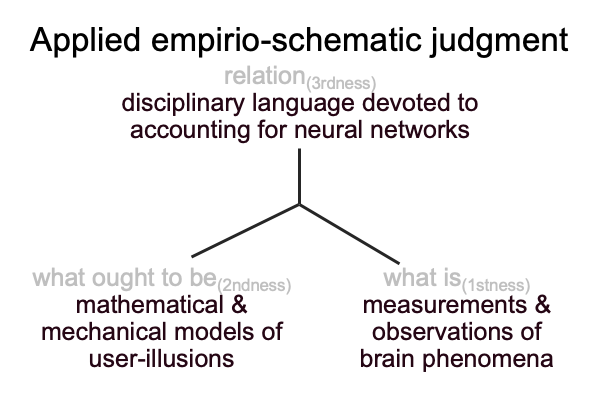

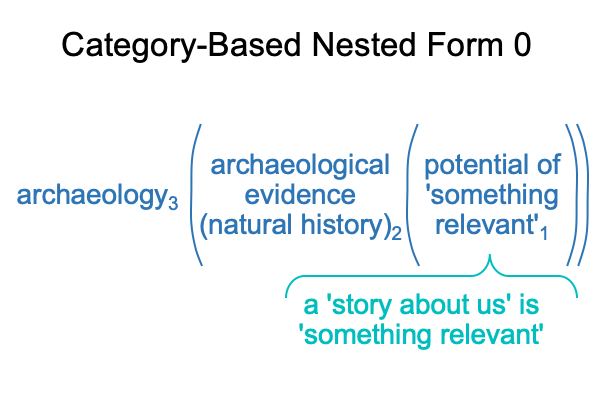

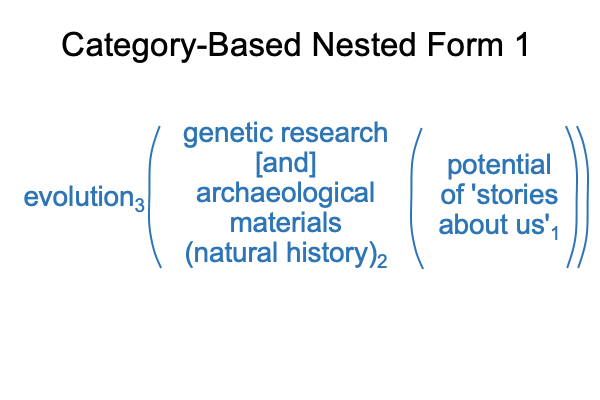

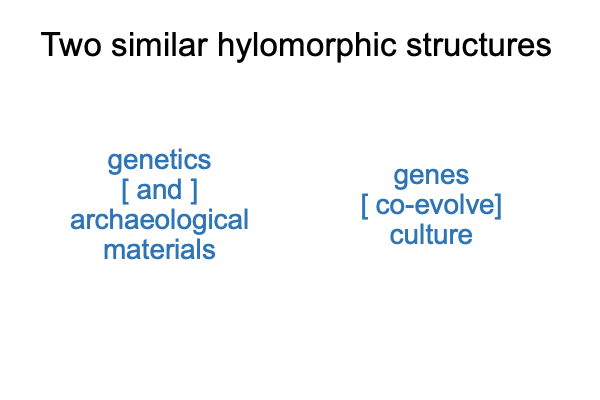

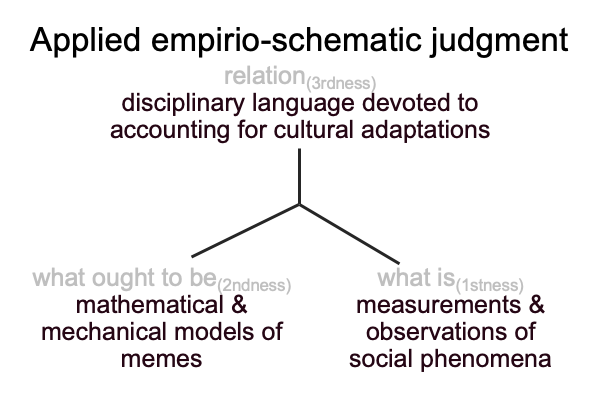

0188 Here is one confounded empirio-schematic judgment characterizing this discussion.

Here is another.