Looking at Alexei Sharov and Morten Tonnessen’s Book (2021) “Semiotic Agency” (Part 1 of 24)

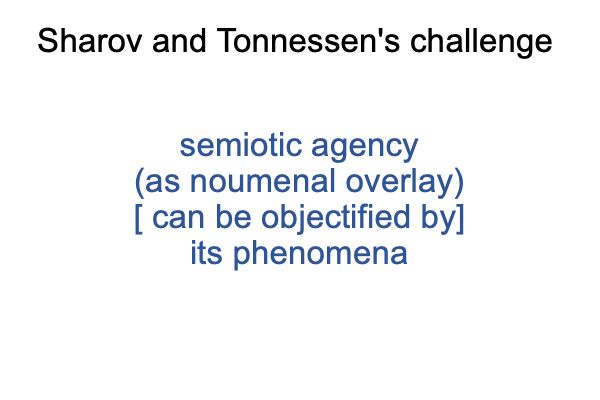

0001 The book before me is Semiotic Agency: Science Beyond Mechanism, by biosemioticians Alexei Sharov and Morten Tonnessen. The book is published in 2021 by Springer and logs in at volume 25 of Springer’s Series in Biosemiotics. Series editors are Kalevi Kull, Alexei Sharov, Claude Emmeche and Donald Favareau. These editors have Razie Mah’s permission for use of the following disquisition, with attribution of said blogger.

Points 0001 to 0226 cover Parts I and III of this book. These Parts are titled, (I) Overview and Historiography and (III) Theoretical Considerations. These two sections set forth the rationale for scientific inquiry into semiotic agency.

0002 Chapter one begins with a question.

Can agency be a scientific subject?

To me, the question, “What is science?”, must be addressed.

0003 Scientific inquiry involves a judgment within a judgment.

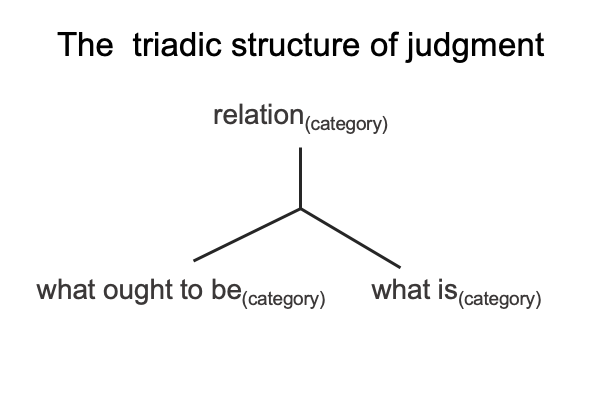

0004 Okay, then what is a judgment?

A judgment is a triadic relation containing three elements: relation, what is and what ought to be. When each of these three elements uniquely associates to one of Peirce’s categories, then the judgment becomes actionable. Actionable judgments unfold into category-based nested forms.

What am I talking about?

Consult A Primer on The Category-Based Nested Form and A Primer on Sensible and Social Construction, available at smashwords and other e-book venues.

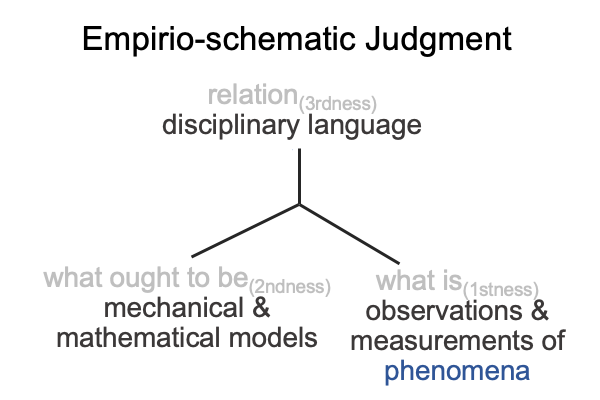

0005 Here is a diagram of judgment as a triadic relation.

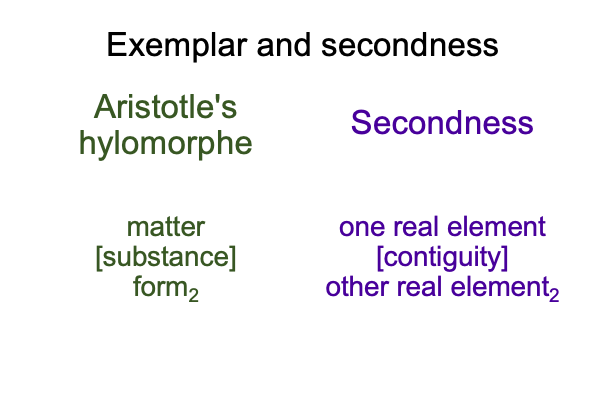

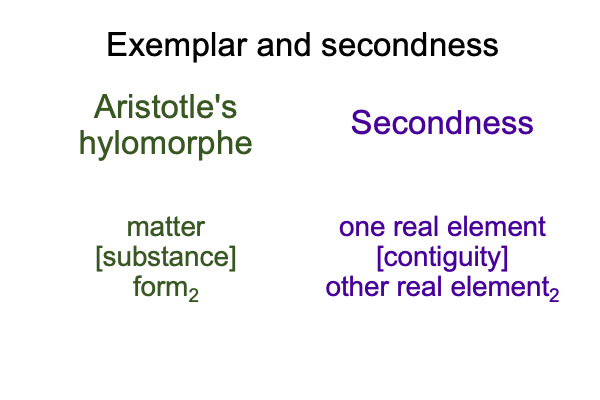

A relation (belonging to one category) brings what ought to be (belonging to another category) into relation with what is (belonging to the one remaining category). Peirce’s three categories are firstness, secondness and thirdness. Firstness is the monadic realm of possibility. Secondness is the dyadic realm of actuality. Thirdness is the triadic realm of normal contexts, mediations, judgments, sign-relations, and so forth.

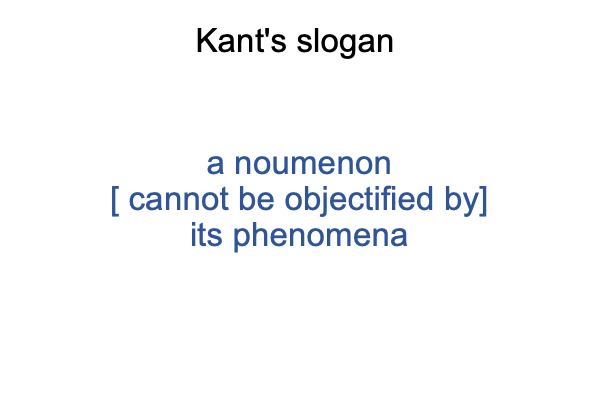

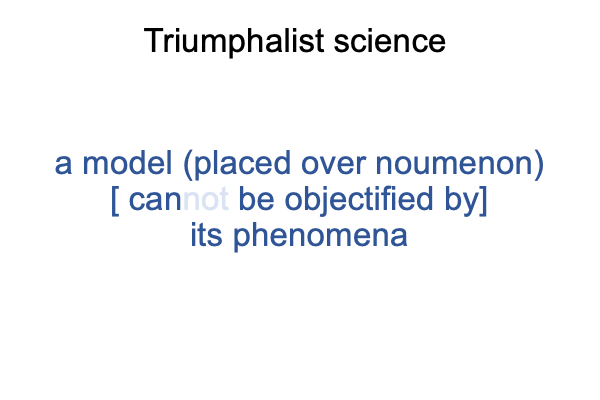

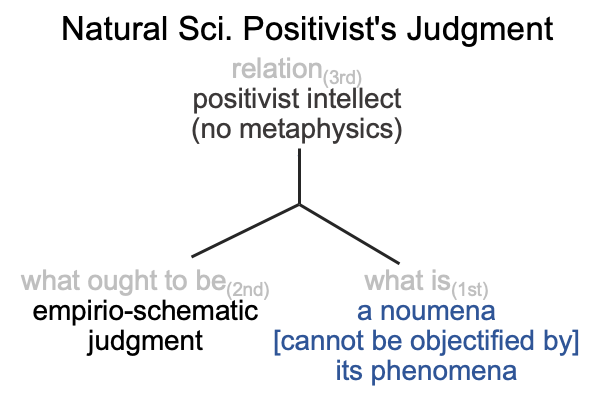

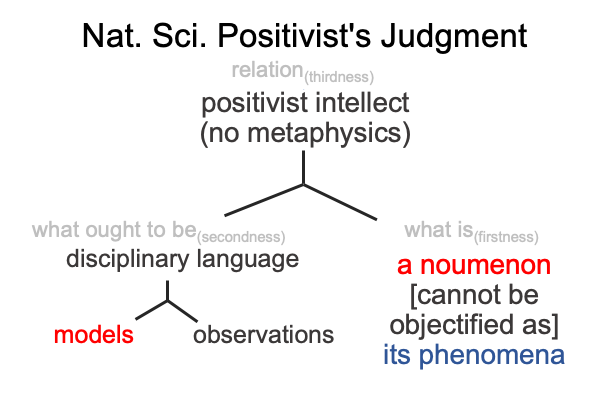

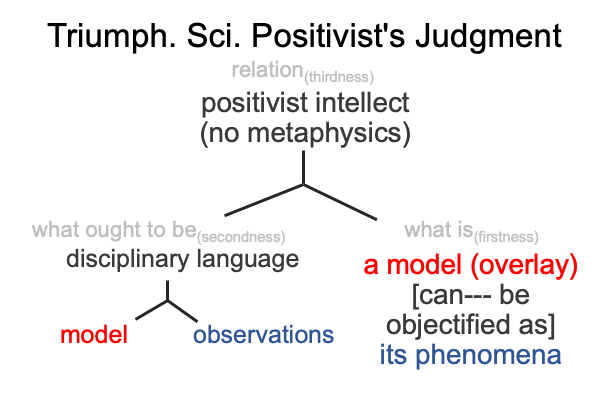

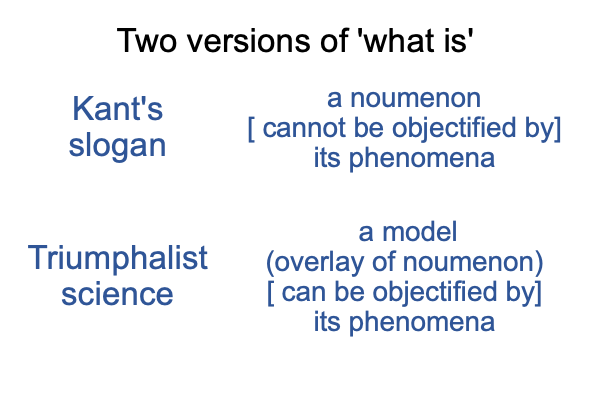

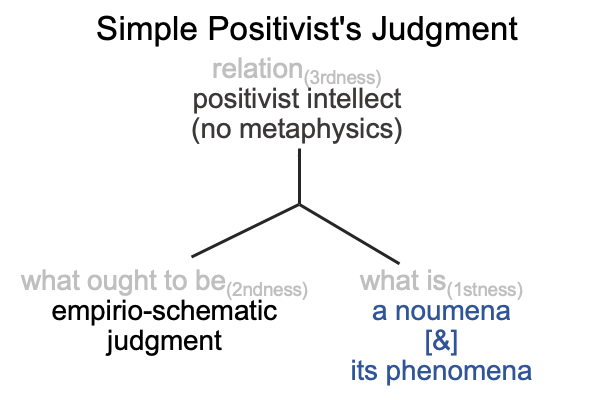

0006 If scientific inquiry involves a judgment within a judgment, then the larger judgment is called the Positivist’s judgment. A positivist intellect (relation, thirdness) brings an empirio-schematic judgment (what ought to be,secondness) into relation with the dyad, a noumenon [and] its phenomena (what is, firstness).

Here is a diagram.

0007 In regards to the relation, the positivist intellect has a rule. Metaphysics is not allowed.

0008 What is “metaphysics”?

Aristotle proposes four causes: material, efficient, formal and final. The first two are (more or less) physical. The second two are (more or less) metaphysical. So, the second two causes are ruled out in the seventeenth century by the mechanical philosophers of northern Europe.

0009 Of course, ruling out formal and final causes truncates material and efficient causalities. Imagine a material cause (such as the flow of ink onto a piece of paper) without its formal cause (the piece of paper will then be folded and put into an envelope). Imagine an efficient cause (the role of glue in sealing an envelope) without its final cause (the envelope will be put in the mail).

So, the rule of the positivist intellect has the effect of truncating physical material and efficient causalities from their metaphysical companion causalities. The positivist intellect is assigned to the category of thirdness, the realm of normal contexts.

0010 In regards to what ought to be, the empirio-schematic judgment belongs to the category of secondness (the realm of actuality), even though it obviously belongs to the category of thirdness, because judgments are triadic relations. In other words, to think in terms of the Positivist’s judgment, one must disregard the obvious and regard the empirio-schematic judgment as an exercise in the realm of actuality, if that makes any sense.

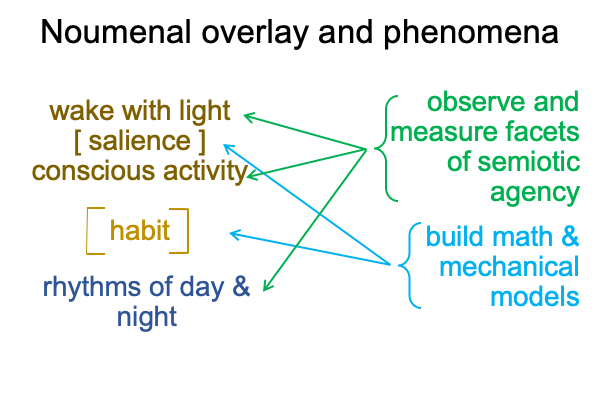

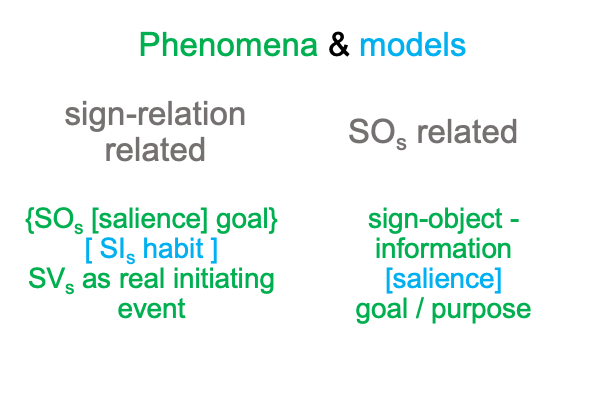

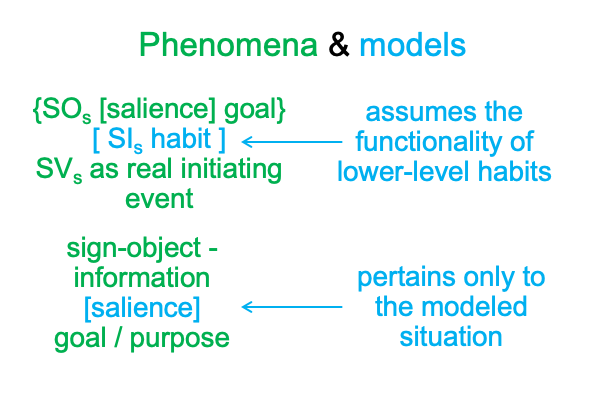

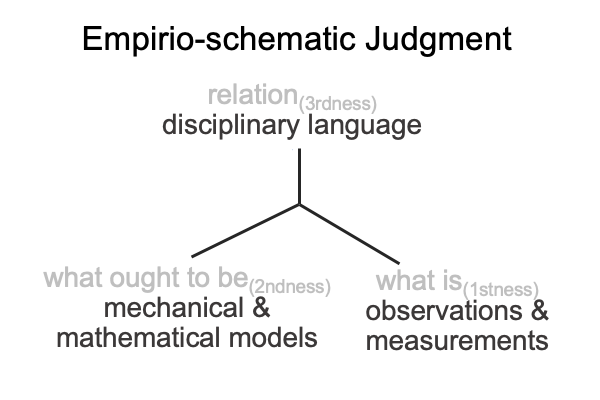

0011 It may help to consider the empirio-schematic judgment as a tool for producing scientific models. Disciplinary language (relation, thirdness) brings mathematical and mechanical models (what ought to be, secondness) into relation with observations and measurements of phenomena (what is, firstness).

Here is a picture.

These figures are initially constructed in Comments on Jacques Maritain’s Book (1935) Natural Philosophy, by Razie Mah, available at smashwords and other e-book venues.