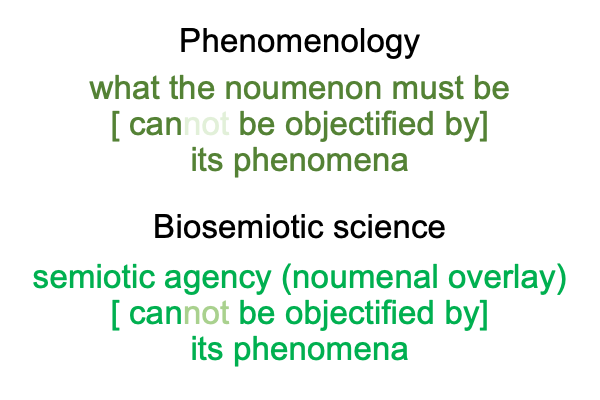

Looking at Alexei Sharov and Morten Tonnessen’s Book (2021) “Semiotic Agency” (Part 21 of 24)

0178 Let me review points 0152 to 0177, examining section 6.1 of Sharov and Tonnessen book.

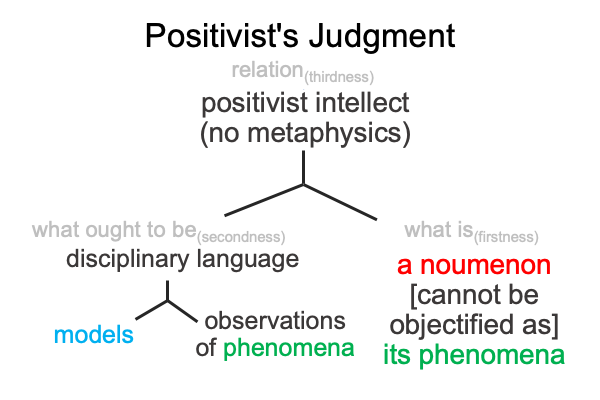

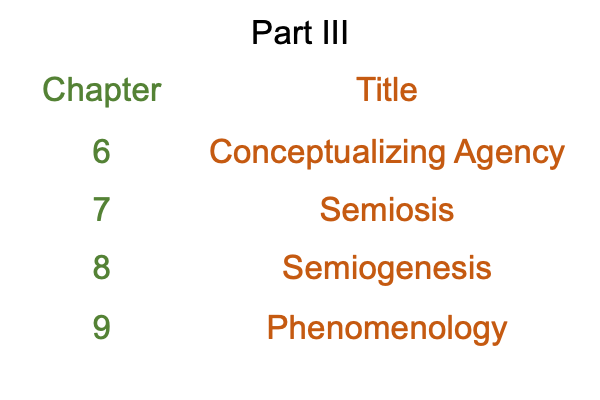

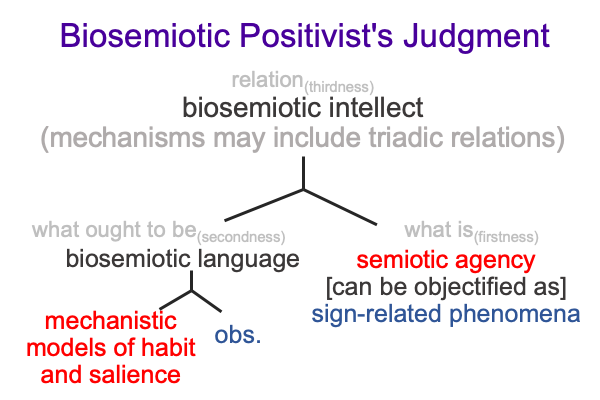

Here is a picture of the biosemiotic Positivist’s judgment.

A biosemiotic intellect (relation, thirdness) brings an empirio-schematic judgment that models sign-interpretants (what ought to be, secondness) into relation with the dyad, semiotic agency [can be objectified as] phenomena related to sign-vehicles and sign-objects (what is, firstness).

0179 Section 6.2 discusses autonomy.

Autonomy associates with self-governance. If an agent has self-governance, then it must have autonomy. Autonomy needs to be accounted for by a mechanistic model for each biosemiotic topic of inquiry.

0180 Autonomy entails several implications.

The first is maintenance (section 6.2.1). The technical term for self-repair is “auto-poesis”.

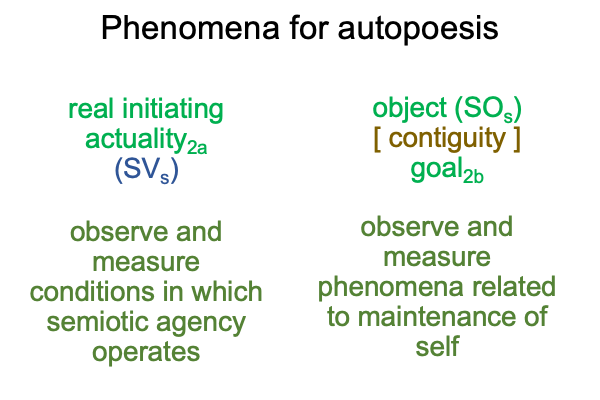

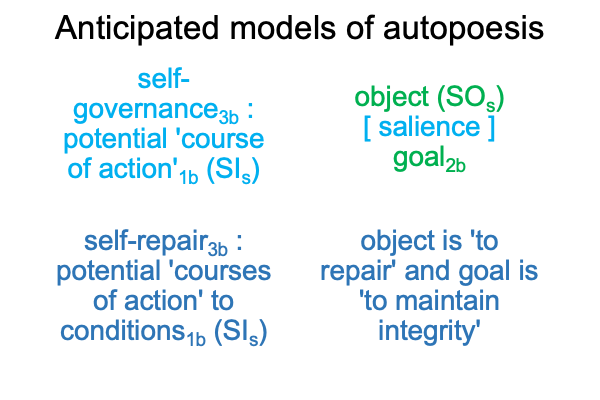

Here is a picture of phenomena related to auto-poesis.

0181 Auto-poesis is obvious in all living organisms. Auto-poesis is not obvious in dead ones.

So, phenomena related to auto-poesis touch back to the idea of wholeness as an attribute for semiotic agency.

With auto-poesis, wholeness requires the functioning of lower-level autonomous systems. These lower-level systems are not whole. They are autonomous systems within a whole system. They are not fully autonomous. But, they can be close to autonomous. For example, I heard of a surgeon who transplanted a heart of a pig into a human and the human lived a couple of weeks.

0182 Well, what about transplanting organs from one human to another?

Yes, that works better, especially if one has a large number of political prisoners who are willing to “donate” their organs.

0183 What am I saying?

I meant to say, “criminals”.

0184 So, what needs to be modeled in regards to auto-poesis?

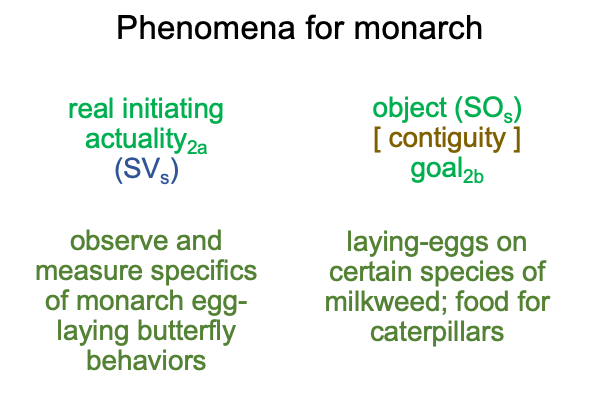

Here is a picture.

0185 Note how the term, “self-governing” (the topic of section 6.2.2) becomes explicit in models for auto-poesis.

Now, if one is talking about organs as “self-governing”, then the term becomes a tad more difficult to explicitly model, outside of a conditional phenomenal qualifier, such as “staying alive”. For example, after removing the cornea from a criminal, and implanting it in a patient in need of a new cornea, the cornea typically does just fine. If one does that with one of the lobes of the liver, the recipient’s immune system must be suppressed, because the patient’s body may recognize the criminal’s liver as a foreign agent. Otherwise, the liver does just fine.

0186 All the organs in an animal body evolve to be interdependent, in so far as they all belong to a single body. And, for humans, they are remarkably resilient when it comes to transplantation. As for removal, I suppose that as long as one organ for every system remains intact, then the entire organism retains its autonomy.

0187 But, what about its “freedom”?

That term associates to potential courses of action.

For example, some criminals may gain their “freedom” after the removal of one cornea, one lung, one lobe of liver, one gonad and one kidney. This liberated criminal remains autonomous without the luxury of organ redundancy.

Other criminals gain their “freedom” after removal of their hearts, along with all those organs that are redundant, because redundancy is no longer necessary once the heart is removed for transplant.

0188 So I wonder, “Is an autonomous agent exhibiting ‘semiotic freedom’ really ‘free’?”

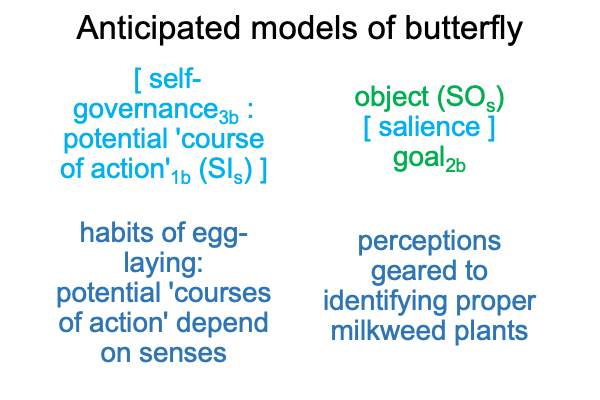

The authors provide the example of egg-laying by monarch butterflies. These butterflies prefer to lay eggs on certain species of milkweed. The milkweed serves as food for caterpillars. Plus, one suspects that the bold-coloration of the butterfly advertises that it once fed on a poisonous plant. If you don’t want to taste milkweed, don’t eat me.

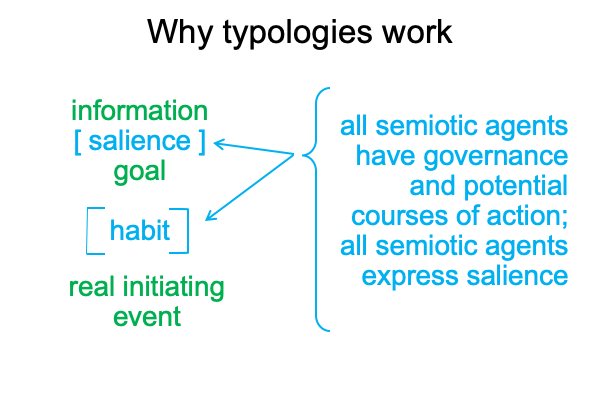

0189 “Semiotic freedom” implies a capacity to sense and perceive. Sensation acts like a sign-vehicle for perception. Medieval scholastics recognize this. Sensation belongs to the content-level for how humans think. Perception belongs to the situation level.

Indeed, models for semiotic agency should account for sensation and perception.

0190 Yes, the term, “semiotic freedom”, captures an irony in biosemiotics as science beyond mechanism. The most robust “models” for semiotic agency are pre-scientific and are couched in (what big government (il)liberals would call) “religious” terminology.

0191 What does this imply?

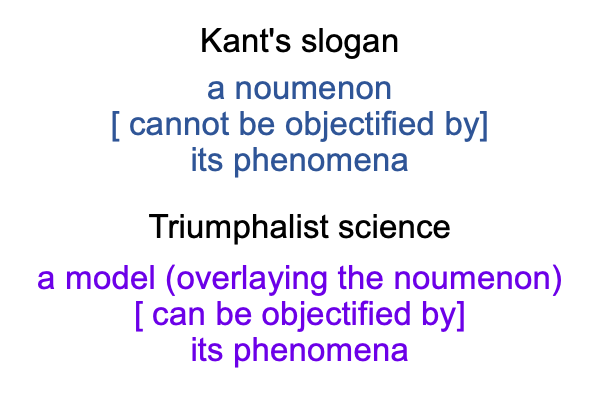

Sharov and Tonnessen’s noumenal overlay works well because it is (as a phenomenologist might say) what the noumenon must be.

Plus, humans are adapted to recognizing noumenon.

That much is obvious.

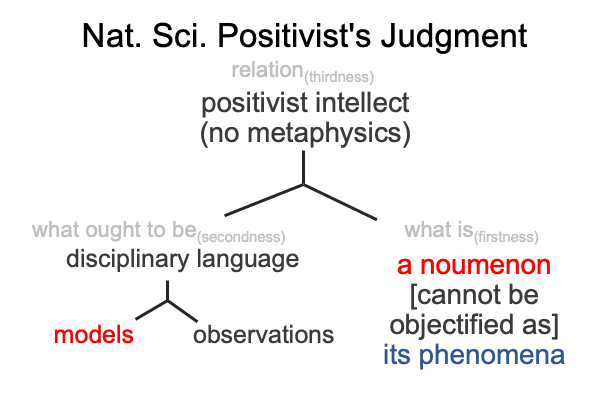

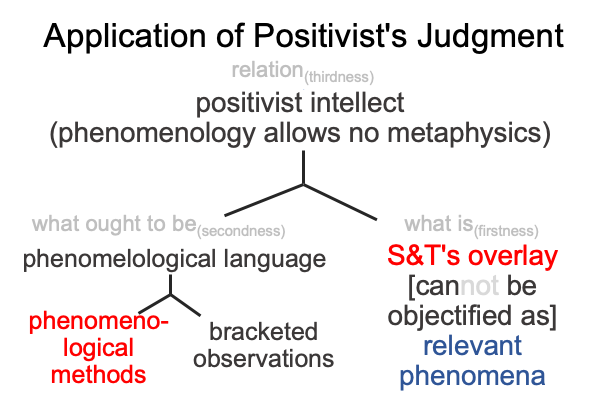

0192 However, as this examiner has already pointed out, the noumenon is precisely the element in the Positivist’s judgment for the natural sciences that the positivist intellect must ignore. In the 1920s, the so-called “Vienna Circle” advocated for the dismissal of the noumenon. Scientific inquiry does not require the thing itself.

Why?

Models constitute the illumination that the Positivist’s judgment actualizes as what ought to be.