0027 Test three.

What does phenomenology3b do?

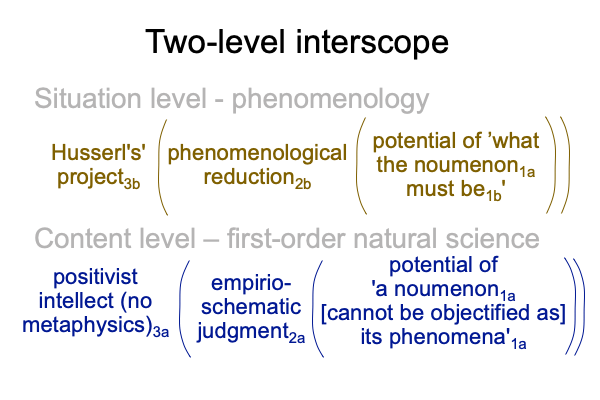

0028 In section three, the authors propose that Husserl’s phenomenology3b approaches reality1a by transcending the explanatory intentionality2a of the exact sciences3a. Reality1a is a noumenon1a and its phenomena1a. The explanatory intentionality2a of the exact sciences is the empirio-schematic judgment2a. Phenomenology3b approaches reality1athrough phenomenological reduction2b.

In sum, phenomenology virtually situates hands-on first-order science.

0029 The authors continue, saying (more or less), “Consciousness (trained in the methods of phenomenological reduction2b) unveils the face of subjectivity (the noumenon1a) that has been eclipsed by positive objectivism (the positivist intellect3a).”

This quote fits the picture of Husserl’s project3b virtually situating hands-on natural science3a.

This quote fits the idea that phenomenological reduction2b elucidates what the noumenon1a must be1b.

0030 Notably, a return to the noumenon1b renders a subjectivity that can be shared by others in the same situation. Phenomenological reduction2b elucidates an intersubjective being1b in the category of firstness, the realm of possibility.

According to the authors, Husserl’s project3b has been criticized for reducing intersubjectivity to the field of consciousness. However, consciousness has already been narrowed by hands-on science to a cogito (the essence of the positivist intellect3a, including the rule of no metaphysics).

So, the terminus of phenomenological reduction2b, what the noumenon1a must be1b (that is, a noumenon1b), is a mind-dependent being, capable of being treated as a mind independent being. I would go as far as to conjecture that this capacity directly correlates to the intersubjectivity of the noumenon1b.