0192 Graeber and Wengrow begin their wide-ranging discussions concerning everything anthropological with a question on the origins of social inequality. In chapter ten, they implicate the state. But, they face a problem. Can the stateaccount for the origins of social inequality if there are no origins to the state?

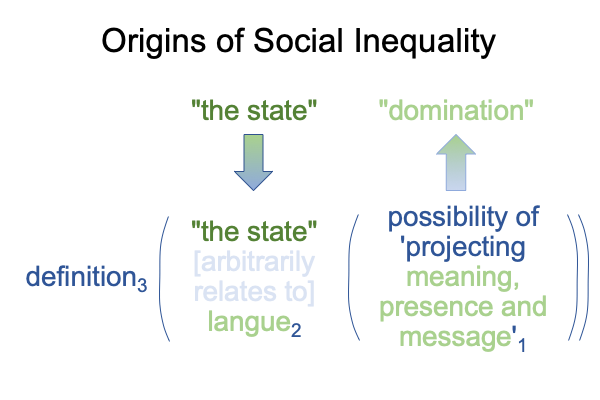

0193 The spoken word, “state”, is the topic of chapter ten of Graeber and Wengrow’s book.

So is the spoken word, “domination”.

Here is a diagram of what these authors may be thinking.

The “state” is a placeholder in a system of differences for speech. Since the spoken word cannot picture or point to anything, as would be expected for hand talk, then we project meaning, presence and message into the langue that is arbitrarily related to this speech act. Graeber and Wengrow explicitly abstract the term, “domination”, as a label for (what I suspect is) the presence or the message underlying the term. The state2 emerges from (and situates) the potential of domination1.

0194 The masterwork, How To Define the Word “Religion”, offers another option.

The option arises while trying to elucidate the presence1 underlying the word, “religion”2. Religion includes institutions. These institutions are different from sovereign power. How so? Righteousness1a is the potential underlying institutions3a. Order1b is the potential underlying sovereign power3b. Order1b belongs to the situation-level of an interscope. Righteousness1a belongs to the content-level.

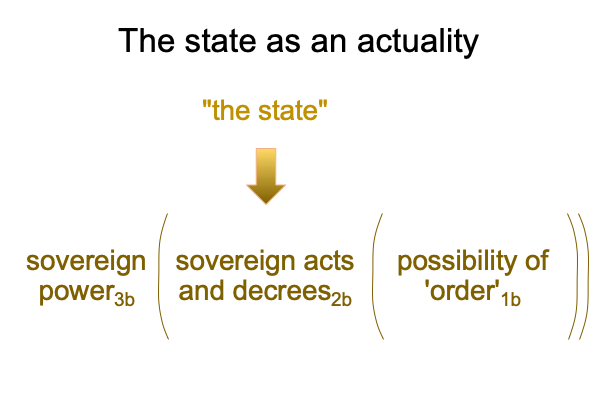

On the situation level, sovereign power3b is the normal context where sovereign acts and decrees2b emerge from (and situate) the possibilities inherent in order1b. Sovereign power3b virtually situates institutions3a.

What we call the “state”2b should correspond to the actuality2b of sovereign power3b contextualizing the potential for order1b.

0195 According to Graeber and Wengrow, the term, “state”, appears in the French lexicon in the late 1500s, about a century after Christopher Columbus’s voyage of 1492 U0′. In the late 1800s, a German philosopher defines the “state” as an institution, within a given territory, claiming a monopoly on the legitimate use of coercive force.

This implies that the term, “state”, labels something more than the actuality of sovereign acts and decrees2b.

0196 Why does the state2b require a monopoly on coercive force?

How else can it enforce order1b?

0197 Does the above figure offer a definition of state2b that is familiar to modern social scientists?

No and yes.

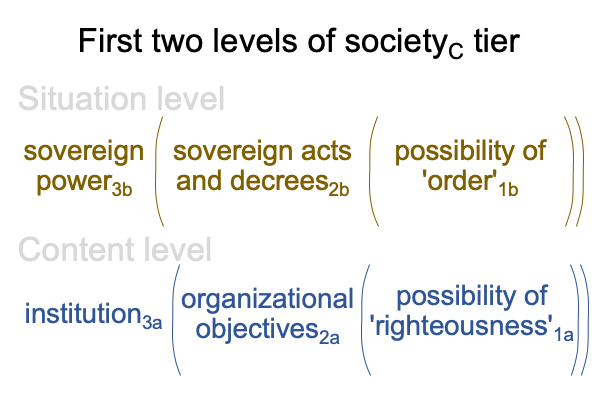

No, this diagram of the “state” as an actuality2 located within a normal context3 and situating a potential1 is innovative. It belongs to the first comprehensive picture in anthropology composed of triadic relations. The diagram relies on the differentiation of nested forms. The first differentiation yields a nested form composed of three terms: society3, organization2 and individual in community1. Second, each of these terms differentiates into a nested form. Third, each element in each nested form differentiates, resulting in a three-level interscope. The result is three tiers of interscopes, corresponding to societyC, organizationB and individual in communityA.

0198 The first two levels of the societyC tier correspond to content-level institutions3a and situation-level sovereign power3b.

Graeber and Wengrow do not know this diagram. Yet, they write as if they do. Social complexityC arises as diverse institutions3aC pursue their organizational objectives2aC, based on a righteousness1aC that interpellates individuals in communityA. In our current Lebenswelt, righteousness1aC calls individuals in communityA into organizationB.

The need for order1bC may arise when institutions compete with one another and come into conflict.

I suppose that may occur when institutions find something to fight over.