0086 Chapter five starts with a snapshot of 100kyr (one hundred thousand years ago). Anatomically modern humans have been around say, since 200kyr.

0087 The authors face a difficulty.

Surely, the fossilized skeletal remains of anatomically modern humans suggest that they are identical to us. At the same time, the cultural continuity between say, 300 to 80kyr is remarkable. So, anatomically modern humans enter into the world and survive for thousands and thousands of years with no rapid cultural innovations.

0088 What are they doing with their enormous brains?

Apparently out of options, the authors suggest that our energy-consuming brains are an advantage when the climate dramatically changes. The climate of the Pleistocene is like a roller coaster. So, the suggestion is plausible.

Or, perhaps, since most adaptations at this time are cultural, cultural adaptations demand enormous brains. Other adaptations to proximate niches are in play as well. For example, small differences in the ability to protect oneself from the sun (with melanin) or from the lack of sun (with no melanin to encourage vitamin D synthesis, which requires sunlight) turn into significant selectors in terms of reproductive success.

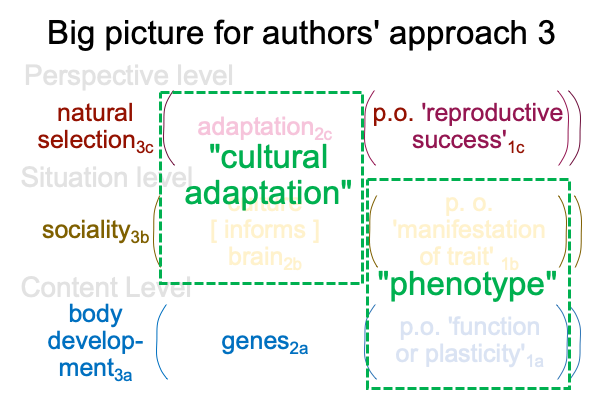

0089 Thus I arrive at the third version of the author’s big picture.

0090 A “cultural adaptation” is a perspective-level behavior or trait2c that influences reproductive success1c virtually contextualizing the situation-level actuality of culture [informs] brains2b. Our large brains are being put to use.

A “phenotype” is a situation-level potential1b, underlying both a cultural trait and its neural substrate2b, virtually emerging from (and situating) neural (or brain) plasticity1a.

Brain plasticity1a favors certain potentials1b over others1b. For example, humans tend to recall stories containing one notable unusual event. If there are no unusual events, the story is readily forgotten (as one expects from sensible thinking). If there are too many unusual events, the story is hard to remember (as one expects from overtaxation of sign-processing).

0091 In one of the interludes, the authors depict a person, using speech-alone talk, rather than hand-speech talk, labeling a situation, “evil”. Surely, the same person could have expressed such an impression without using the spoken word, “evil”.

How about a grimace?

Hand-talk the offender’s name then grimace, with exaggeration.

How does one picture or point to a situation using hand-speech talk?

One cannot. One can only image and indicate a sign-vehicle within the situation. Then, the others must make the connection between that gestural-word and the nasty face. The unhappy family member juxtaposes two signs, gestural-word and grimace. What does that imply?

Everyone, to some extent, must guess.

0092 Is that not the nature of sign-processing? Given a sign-vehicle, say a really sharp rock fashioned to the end of a long wooden shaft, one must guess the sign-object. So, having a well routinized sign-interpretant makes good sense. No one wants to end up on the wrong end of that stick.

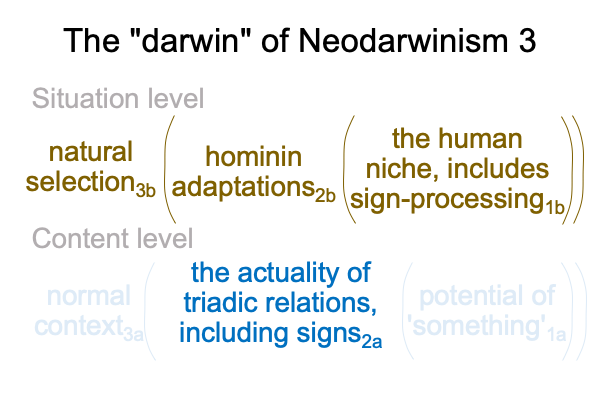

0093 To me, the fact that the authors do not recognize that the human niche entails sign processing sets the stage for a lot of hand-waving as the story about human evolution comes closer and closer to our current Lebenswelt.

0094 The human niche includes the potential of sign-relations.

Signs are triadic relations.

So, what does that say about the human niche?

If the authors had only encountered the hypothesis proclaimed in Razie Mah’s e-book, The Human Niche (available at smashwords and other e-book venues), then they really could have worked their imaginations.

So many stories can be told.