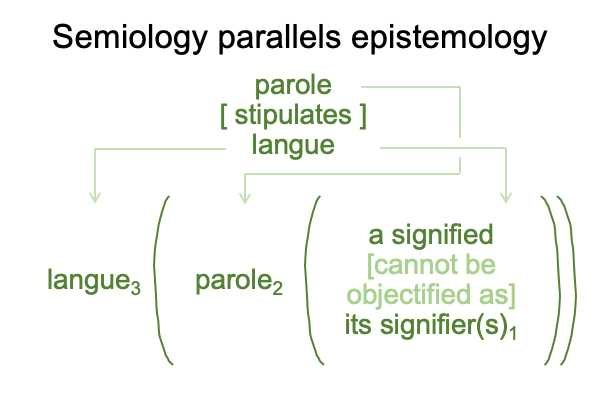

0024 What is odd about Saussure’s semiological and Decartes’ thinking-thing formulations is that the apparent dyadic actuality unwinds into something actual2 (parole2) as well as something that empowers an understanding of something actual3((1)), the normal context of langue3 and the potential that a signified [cannot be objectified as] its signifier1.

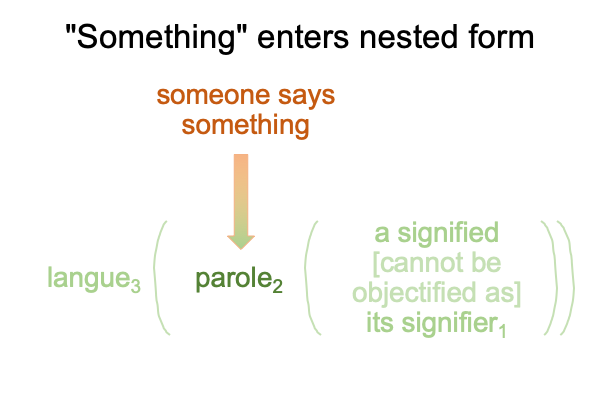

0025 This unwinding produces a nested form where someone saying something becomes Saussure’s parole2, in the normal context of langue3 (what is going on in one’s mind) with its potential that the signified [cannot be objectified as] the signifier1.

0026 What does the normal context of langue3 mean?

Langue is French for “language”. It roughly corresponds to what is going on in one’s head during conversation in speech-alone talk. For Saussure, langue consists of a system of differences. As a normal context3, langue3 can be regarded as a highly evolved sorting machine, where a spoken word2 is paired to a potential signified1, all the while knowing that the spoken-word2 signifier1 does not really objectify the thing itself1. Neither does the mental-process signified1, even though the mental-process1 stands in the place of the thing itself1.

Does this make sense?

0027 What does the potential of a signified [cannot be objectified by] its signifier(s)1 imply?

Well, it seems that a signifier1 potentiates parole2, as each signifier1 fills a place in vocal system of differences2. The corresponding signified1 underlies langue3, in so far as it1 occupies a place in a mental system of differences.

Plus, parole2 belongs to secondness, the realm of actuality, langue3 belongs to thirdness, the realm of normal contexts3, and the signified-signifier distinction1 belongs to firstness, the realm of possibility1.

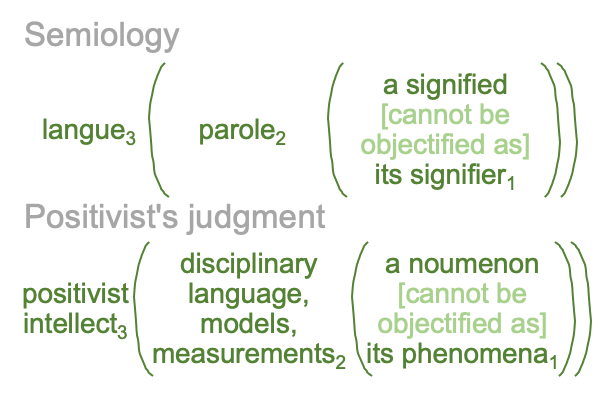

Furthermore, Saussure’s semiology can be compared to the Positivist’s judgment, insofar as both may be portrayed as category-based nested forms.

Semiology applies to spoken language. The Positivist’s judgment applies to scientific inquiry into nature.

0028 Note that the actuality2 of the Positivist’s judgment is the empirio-schematic judgment2, which consists of three elements: relation (disciplinary language), what is (measurements) and what ought to be (mathematical and mechanical models). A judgment brings what is and what ought to be into relation.

The comparison bears fruit with the realization that semiology’s parole2 corresponds to an empirio-schematic actuality2that includes parole2, in the style of a disciplinary language (relation)2. Both models (what ought to be)2 and observations (what is)2 are couched in terms of a disciplinary language (relation)2.

Plus, signifiers1 are comparable to phenomena1. A signified1 is comparable to a thing itself1.

Finally, the positivist intellect3 appears to be a style of langue3.

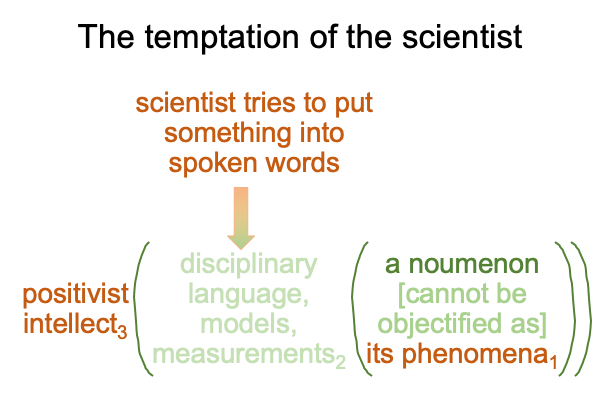

0029 What is interesting is the sequence of events in semiology and in the Positivist’s judgment. For semiology, a speech act2 enters into the slot for actuality2 and activates the langue3 signified-signifier1 machine. For the Positivist’s judgment, the positivist intellect3 is always promoting awareness of phenomena1 in such a manner that a scientist tries to put something (perhaps, corresponding to a noumenon) into words2. So, the normal context3 and the potential1 are hoping for and are prepared for a particular style of actuality2.

0030 What does this imply?

Both Descartes’ and Saussure’s dyads have the structure of secondness. Descartes and Saussure, each in his own way, promote the idea of the human as a res cogitans, a thing that thinks. When these two speak of “relation”, they mean the dyadic structure of cause and effect.

Typically, a hylomorphic structure enters the slot for actuality2 in a category-based nested form. This fosters understanding.

However, we do not try to understand these dyads. Instead, we unfold these dyads into category-based nested forms, in a systematic fashion. One element of the dyad associates to actuality2. The other element of the dyad associates to both normal context3 and potential1. One element of the dyad becomes like a fly. The other element of the dyad becomes like the spider’s web.

0031 These lines of thought, using only category-based nested forms, supports Deely’s contention that humans are semiotic animals, rather than rational animals (a modern and a premodern view) or thinking things (a modern view).

Peirce publishes his New List of Categories on May 14, 1867. Deely suggests this moment as the inaugural date for The Age of Triadic Relations.