0049 Deely begins chapter seven by noting that Baroque scholasticism concludes (around 1650-1700) and Peirce begins (around 1850-1900) with the same question, “What is the nature of signification?”

0050 Modern science does not help.

No scientist can put a sign-relation directly under a microscope. But, a scientist can observe and measure one or two of the termini. Often, the sign-vehicle and the sign-object (the proximate fundament) presents scientists with phenomena, which are duly measured and used to build models of sign-behavior. Consequently, the sign-relation, the thing itself, can be put into a variety of boxes, each labeled “noumenon”, for each suite of phenomena produced by that sign-relation.

0051 After all, science does not worry about noumena. It only observes and measures their phenomena.

Did I say that correctly?

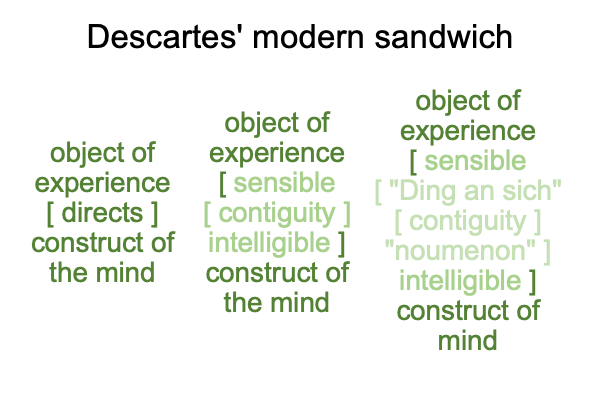

0052 Deely notes that Kant makes a fine distinction between the term, “noumenon”, the intelligible aspect of things, and “Ding an sich” (German for “the thing itself”), the sensible aspect of things.

To me, this aside calls to mind a Cartesian version of Saussure’s sandwich.

So, in my book, “noumenon” and “the thing itself” coincide.

0053 Here is a twist.

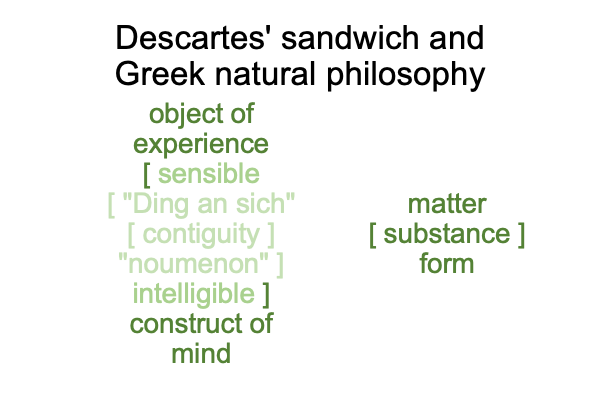

According to ancient Greek philosophy and scholasticism, a thing should be both sensible and intelligible.

Does matter go with sensible? Does intelligible associate to form?

If they do then, oops, the big modern sandwich gets pressed into a panini.

0054 Charles Peirce calls the modern inquirer back to the approaches of the old philosophers, by saying that sign-vehicles cannot serve as phenomena that cause associated behaviors. A stop sign does not cause a moving automobile to slow to a rolling standstill anymore than a fly causes a hygienist to swat it. A stop sign represents the laws of the road. A fly represents potential contamination and disease.

The term “represents” is a substitute for “stands for”.

Consequently, science-mavens propose variations and descriptions of the term, “stands for”, when they describe the nature of humans. Humans are rational animals. Humans are signifying creatures. Humans are a symbolic species. The list is long.

0055 Further confusion follows with the following set of statements.

I experience my world as subjective, since I embody the potential for sign-objects.

My world is subjective, since the world is the subject matter of my experiences.

I experience the world as objective, since my world is perfused with sign-vehicles.

Sign-objects are objective, because they are objects, not things.

We experience our world as intersubjective, because several of us can embody similar sign-objects in response to a single… um… subjective sign-vehicle.

Even though we may encounter the same sign-vehicle, we are not thinking precisely the same sign-object because we have different bodies. However, the sign-objects that we are thinking have relational structures so similar that they may serve as one sign-vehicle.

So, our objective sign-objects become an intersubjective sign-vehicle.

The resulting sign-object is suprasubjective. The suprasubjective sign-object may be judged. Indeed, the suprasubjective sign-object may even constitute a judgment. So, our own judgments may be couched in suprasubjective frameworks, such as the dichotomy of true versus false or honest versus deceptive.

0056 Do I notice that there are two sign-relations in this set of statements?

There is a sign-relation that seems to be properly a sign-vehicle standing for a sign-object in regards to a sign-interpretant.

Then, there is sign-relation according to the human as a semiotic animal. The Latins called this relation, “relatio secundum esse” (a relation according to esse_ce, where esse_ce describes, not the essence of, but the presence of humans). I don’t know whether the sign-relation whose sign-vehicle is intersubjective precisely corresponds to the Latin term. But, the possibility intrigues.

0057 In section 8.1, Deely discusses how triadic relations challenge scholastic philosophers who are trained to draw distinctions.