0097 How does anyone know when what is out there is real?

Wisdom will tell. That is why the word, “philosophy” is Greek for the love of Sophia. Sophia is the personification of wisdom.

0098 Aristotle formulates his list of categories in order to specify ways in which a finite mind can verify independent existence. This list contains features that a being of reason (ens rationis) would need to verify in its encounter with mind-independent being (ens reale).

0099 What does this imply?

Twenty-five centuries after Aristotle, a self-promoting psychoanalyst, Sigmund Freud, tells me. Dreams are the fulfillment of unconscious wishes, desires and beliefs.

Consequently, Aristotle’s categories are dream-elements that allow the inquirer to… um… step out of his or her sleep-walking.

0100 The term, “relation”, appears on Aristotle’s list.

With this observation, Deely begins his discussion and spends the remainder of chapter eight, and all of nine, recounting how philosophers wrestle with this term, “relation”, for thousands of years. Their contest concludes with the Baroque scholastic, John Poinsot.

0101 Here is the crux.

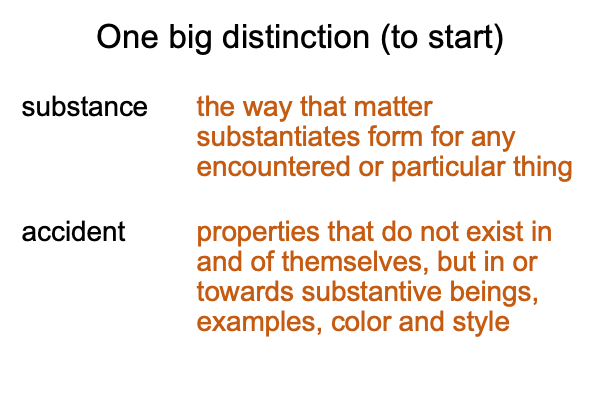

All the other terms in Aristotle’s list allows one to distinguish between substance (the way that matter substantiates form) and accidents (properties that do not exist in and of themselves, but in and of substantive beings). A substantive being has the character of ens reale. An accident is more like… well… something with the character of ens rationis. It’s realness depends on someone noticing it.

0102 Deely attributes a long period of philosophical meandering to the distinction between substance and accident. Flowers are substantive. Bees are substantive. What about the relation of flowers and bees? Well, “relation” is on Aristotle’s list. So, it must be substantive. But, this relation is neither flower nor bee. Perhaps, it is real if someone notices it. Doesn’t that sound vaguely postmodern? A text is real only in the reading.