0061 In chapter four, Farrell introduces the reader to Gottfried W. Leibniz (1646-1716 A.D.), a polymath in a century filled with polymaths. Leibniz writes volumes. Many of his works are not translated into English. So, let the reader beware. At the same time, let that not deter us. Farrell picks up a translation of a short article (circa 1696) titled, “On the Principle of Indiscernibles”.

0062 I suppose that, if one tries, one can discern something.

But, what if that ‘something’ is indiscernible?

0063 Leibniz writes (I follow Farrell’s quotation), “All that we have said here arises from that great principle, that the predicate is in the subject.”

Does this apply to the Tower of Babel story?

Here is my guess.

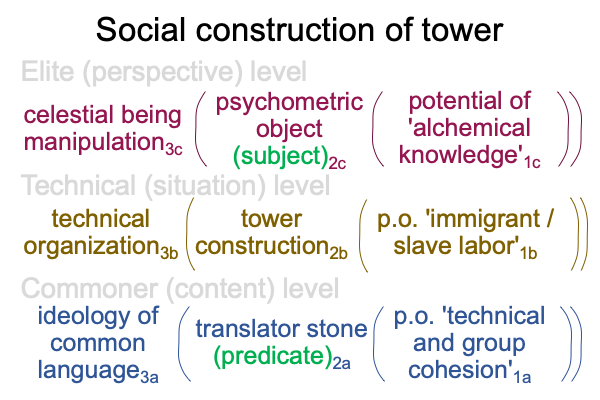

0064 The translator stone2a is a predicate. It2a is a psychometric object that actualizes the potential of ‘group cohesion’1awhile sustaining a normal context, the ideology of a common language3a, that maximizes that potential1a.

The Tower of Bab-ilim2c is a subject. It2c is the psychometric object that actualizes the potential of ‘alchemic knowledge’1c while sustaining the hidden normal context3c, the manipulation of celestial beings3c, which may include “stars” like Nimrod, a mighty hunter and, no doubt, ruthless psychopath. The administrators want Nimrod’s name on a tower that puts the Egyptian pyramids to shame.

0065 Leibniz’s proclamation concerns the principle of indiscernibles.

Farrell passes into the mists of that principle.

Who can discern, in the haze of a story about the confounding of languages, a Tower of Babel moment, which, to me, corresponds to the loss of efficacy of a translation stone?

0066 Does Farrell suggest that Leibniz seeks to recover the translation stone of translation stones, one that brings us to the beginning, that is, to the time when speech is added to hand talk, in the form of anatomically modern humans?

From this moment of divergence, all spoken languages radiate in time and space, except for a handful of isolates. And, never mind about the issue of hand-speech talk.

This is not about isolates or hand-speech talk.

0067 Leibniz seeks to discern a translation stone that puts the one in the land of Shinar to shame. Leibniz invents the calculus. Plus, he envisions a lost form of philosophical analysis that imitates the calculus, in so far as it translates nature’s language into human discourse. All that is needed is a map. A topogram. A translation stone.

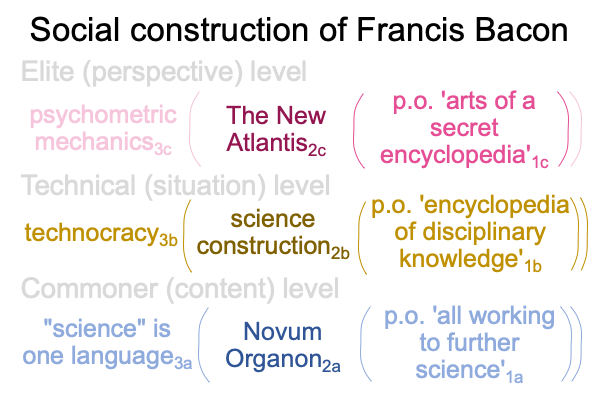

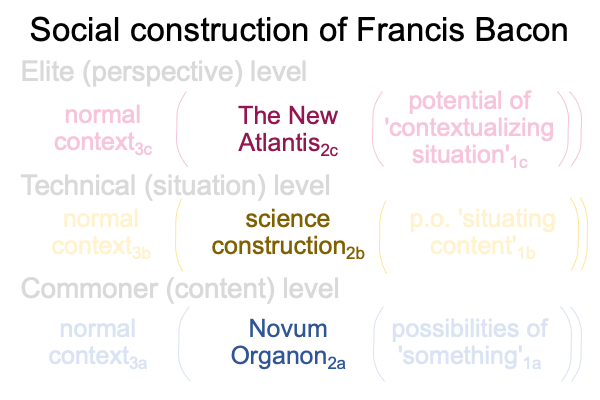

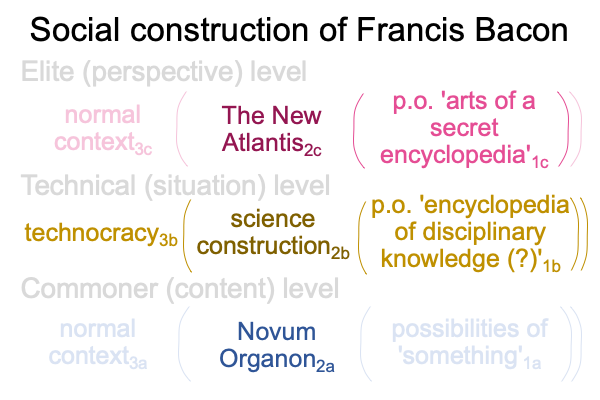

Leibniz is not alone in his search for “characteristica universalis”. Francis Bacon (1561-1626 AD) writes his own fictional manifesto, The New Atlantis, as an epilogue to his mechanical-philosophy oriented Novum Organon.

0068 Does Bacon’s towering manifesto and topographic mechanical philosophy overlay onto the actualities of the Tower of Babel construction?

Here is how that might look.

0069 Okay, back to Leibniz.

In 1679, a work entitled, “An Introduction To A Secret Encyclopedia”, circulates among later-to-be labeled, “enlightenment” thinkers.

An Introduction To A Secret Encyclopedia mentions technocracy.

Now, if I were to put “technocracy” into the above interscope, then what slot would I choose?

How about the situation level normal context3b?

0070 Leibniz presents a long list of the arts involved with a complex administration of the secret encyclopedia.

Where do these arts go?

Perhaps, they go with the perspective-level potential1c.

Here is my prior guess, adjusted.

0071 Farrell highlights one of the arts: the art of subtlety.

This art is on display in Looking at Daniel Dennett’s Book (2017) “From Bacteria, to Bach, and Back”, appearing in Razie Mah’s blog during the month of December 2023.

0072 Indeed, this reader suspects that Farrell’s line of thought is designed to carve a deconstructive path into the art of subtlety, as well as the art of the obvious, in order to allow entrance to those who, like himself, are neither commoner nor aristocrat.

The art of the obvious pertains to what is intersubjectively accepted by commoners as “objective”. Yes, the translator stone is real. It is more real than the plain observation that the people of the Shinar plain speak Sumerian and Akkadian. The translation stone is a psychometric object capable of altering social conditions.

The art of subtlety pertains to what is subjectively accepted by the commoner as “suprasubjective”. Yes, the translator stone verifies the ideology that we all speak a common language and therefore, are one people. If many people believe it, then that turns the translation stone into a psychometric object.

Yes, both arts are at work in the psychometrics of the translator stone2a and the Tower of Bab-ilim2c.

0073 All sorts of philosopher stones have been fashioned.

I suppose that, in the beginning, one of them worked as advertised.

What Farrell points out, in his spiral-staircase ascent through his deconstructive augur, is that all the nascent figures of the western enlightenment, suspect that this is the case. All that we need to do is rediscover the one philosopher’s stone that works. A translator stone connects us to the beginning of human kind, even to before the beginning of our kind. A philosophical instrument translates the language of nature into the language of humans. This alchemical recipe will even convert lead into gold.

0074 And so, I may pencil in a few more elements to Francis Bacon’s own Bab-ilim.