0067 The year, 1935 AD, stands in the interim between the “First World War” and the “Second World War”.

Remember, these terms are modern labels for two brief historical periods.

Jacques Maritain publishes his book in the interim. He lives in France, where Christendom faces an apparently mortal enemy: Modernity.

0068 Modernity has modern science in its arsenal. Christendom has… um… a newly revived Thomism, apparently ill-suited for the intellectual fashions coming from allegedly “scientific” movements, such as Darwinism, Marxism, Saussure’s linguistics, Husserl’s phenomenology, quantum physics, and so on. Catholic intellectuals in Paris, a former epicenter of medieval scholasticism, ask, “What is the nature of science?”

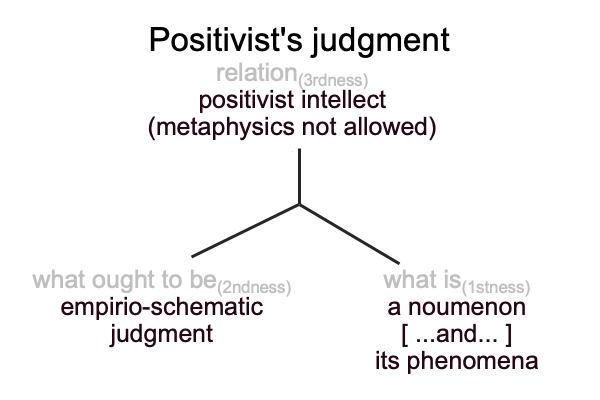

Maritain’s answer may be diagrammed according to the triadic structure of judgment. A judgment contains three interlocking elements: relation, what is and what ought to be. A judgment is a relation between what is and what ought to be. When each element is assigned one of Peirce’s categories, then the judgment becomes actionable. Actionable judgments unfold into category-based nested forms.

0069 Here is a picture of the Positivist’s judgment.

0070 A positivist intellect (relation) brings a noumenon […and…] its phenomena (what is) into relation with an empirio-schematic judgment (what ought to be).

0071 Note that two judgments are entangled. The empirio-schematic judgment is embedded within the Positivist’s judgment. The empirio-schematic judgment is what ought to be. It is also imbued with the category of secondness, the realm of actuality. To the scientist, a model is more real than its supporting observations and measurements. How so? One may make predictions about future observations and measurements based on the model.

0072 Also note that what is has a hylomorphic structure, even though it belongs to the category of firstness, the realm of possibility. Aristotle presents an exemplary hylomorphe: matter [substantiates] form. This hylomorphe fits Peirce’s category of secondness. Secondness consists in two real contiguous elements. For Aristotle’s hylomorphe, the real elements are matter and form. The contiguity is labeled “substance”. For clear nomenclature, I place the contiguity in brackets.

In the above figure, the substance labeled “…and…” is far more complicated than it appears. The full hylomorphe is a noumenon [cannot be objectified as] its phenomena. […And…] is short for […cannot be objectified as…].

Perhaps, it will be no surprise that the noumenon associates to Dennett’s term, “manifest image”.

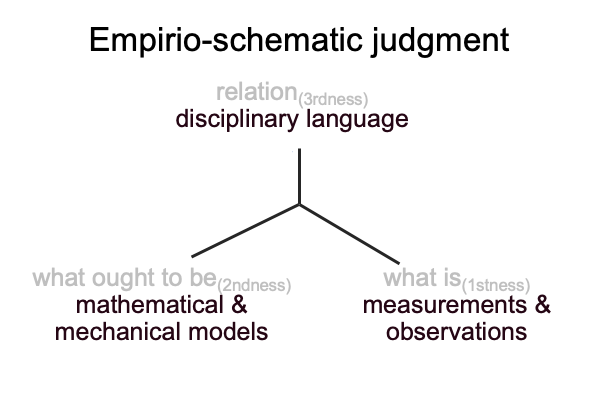

0073 Dennett’s scientific image is located in what ought to be for the Positivist’s judgment. Here is a picture of the empirio-schematic judgment.

0074 How do diagrams of the Positivist’s and empirio-schematic judgment illuminate Dennett’s subliminal… or is it sublime?… defense of the Positivist’s judgment?

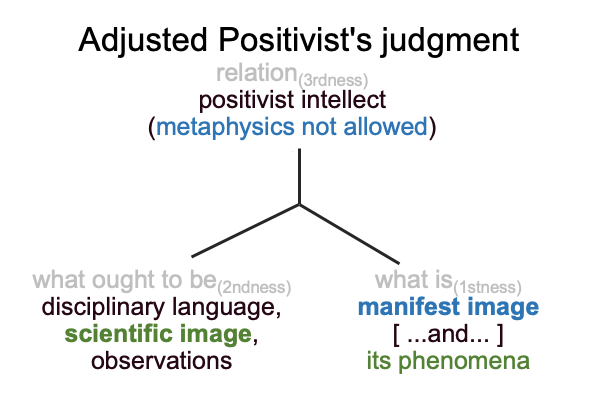

To start, I wonder, “What elements associate to the manifest image and to the scientific image?”

Well, obviously, the manifest image and the noumenon go together.

The scientific image matches mathematical and mechanical models.

0075 Here is a result of the substitutions.

0076 Ah, the manifest image is already proscribed by the rule of the positivist intellect. The manifest image is not the thing itself. It is a sensation2a, a phantasm2b or a judgment2c concerning the thing itself. The manifest image calls to mind the actualities within the scholastic interscope about what is going on in an individual’s mind.

Plus, the scientific image is constructed from observations of phenomena that cannot fully objectify the manifest image… er… our mind’s response to a noumenon, a thing itself.

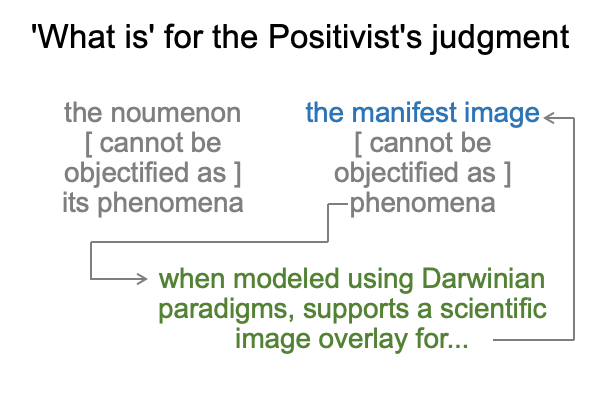

0077 Here is a comparison of what is for the standard version and for the adjusted version of the Positivist’s judgment.

0078 What does this imply?

Dennett’s defense of the Positivist’s judgment is neither subliminal nor sublime. It is subtle, in precisely the way that philosophers employ subtlety. The fact that the phenomena of neural synapses and (I will get to this later) cultural memessupport the manifest image as a multifaceted evolutionary adaptation (that may be modeled using neuronal and cultural Darwinian paradigms) implies that the manifest image may be dispensed with, because it is an user-illusion of the scientific image.

Does this tell me that the noumenon, the thing itself, is what humans are conscious of?

Or is the noumenon what humans adapt to according to neuronal and cultural Darwinian paradigms?

0079 My user-illusion is an adaptation, as substantial as a dog’s fierce jaws and a cat’s sharp claws. It cannot be dispensed with, lest I die.

In the face of subtle distinctions between the noumenon and the manifest image and between the manifest image and the scientific image, the betting man would place his money on the manifest image, as that which will endure… er… survive, rather than the scientific image. Dennett argues against this bet, but he cannot speak directly, because his scientific discussion supports the betting man’s conclusion.

0080 If our consciousness of species impressa2a and species expressa2b is an adaptation, then how is the proposed scientific accounting of our impressions2a and perceptions2b supposed to make them more adaptive? And if Dennett’s argument succeeds, and a scientific image based on Darwin’s paradigm overlays our feelings2a and phantasms2b, then what about what humans think?

0081 The long-debated scholastic picture of the way humans think cannot be lightly discarded.

Only a subtle argument will suffice.