0166 Tabaczek’s introduction summarizes some of the material in Emergence.

Everyday science focuses on “truncated” material and efficient causes. “Truncated” represents “a divorce from formal and final causation”.

Typically, material causes meet the requirements of formal causes and efficient causes are intentionally bound to final causes. So “truncated” also implies that a scientist may surreptitiously slip formal and final causes into his models by defining terms in such a way that they appear to describe modern material and efficient factors, while harboring the shadows of the other causalities.

0167 For example, consider the claim that glucose tastes sweet because it is full of calories.

Yes, that sounds like truncated material and efficient causalities.

Plus, there is the added hint of formal (calories is a formal requirement) and final (sweetness is an incentive) causes.

0168 Why do scientists rely on truncated material and efficient causalities?

These serve as constants and variables in mathematical and mechanical models.

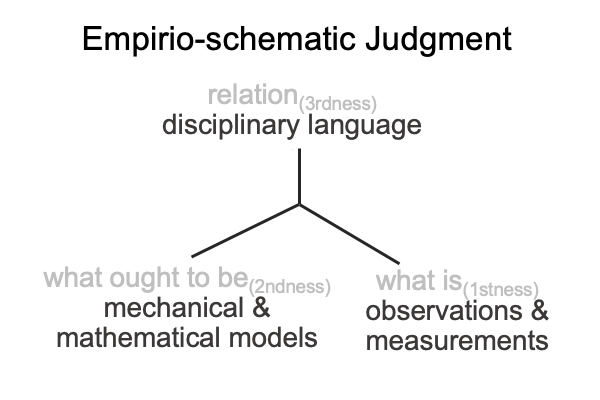

Models are what ought to be (secondness) in the empirio-schematic judgment. The category of secondness is the realm of actuality. So, oddly enough, models are more actual than observations and measurements (what is, firstness, the realm of possibility).

Here is a picture.

0169 The empirio-schematic judgment describes the actual practices of modern science. Disciplinary language (relation, thirdness) brings mechanical and mathematical models (what ought to be, secondness) into relation with observations and measurements (what is, firstness). Since each element is assigned to one of Peirce’s categories, the judgment is actionable. An actionable judgment unfolds into a category-based nested form on the basis of the assigned categories.

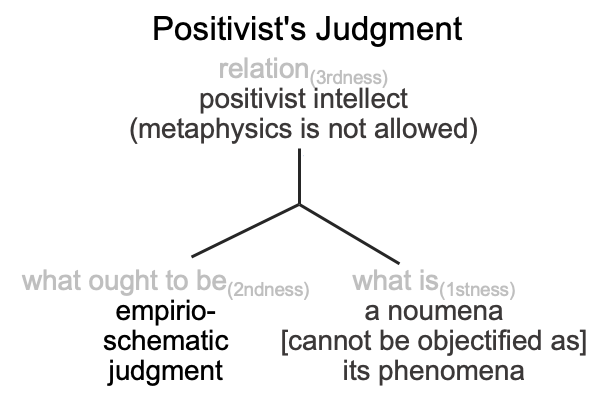

The empirio-schematic judgment corresponds to what ought to be (secondness) in the Positivist’s judgment, where a positivist intellect (relation, thirdness) brings the empirio-schematic judgment (what ought to be, secondness) into relation with the monadic “hylomorphe”, a noumenon [cannot be objectified as] its phenomena (what is, firstness).

The thing itself cannot be objectified as its observable and measurable facets.

0170 Here is a diagram.

0171 Now I have a question concerning ‘what is’ in the Positivist’s judgment.

If hylomorphes exemplify Peirce’s secondness, then why is this “hylomorphe” assigned to the category of firstness?

A hylomorphe may be assigned to firstness, when both sides of the hylomorphe correspond to the same thing. Why? There is only one (not two) real element(s). In other words, if there is no noumenon, then there are no phenomena. If there are no phenomena, then it is doubtful that there is a noumenon.

0172 An apparently sleeping student suddenly raises a hand and asks, “But, if there are phenomena, but there is no noumenon, then can one assign a noumenon and pretend that it is the thing itself?”

Then another student pipes in, “And what about when a noumenon does not have any phenomena, but one is certain that the thing itself must exist? Based on the conviction that there is a noumenon, can one identify its phenomena?”

0173 Uh-oh. I should not have asked that question.

Meanwhile, since each element in the Positivist’s judgment is assigned to one of Peirce’s categories, the judgment may “unfold” into a category-based nested form.