0292 What about agent-metaphysicians?

0293 What do they regard when looking at their own reflections in the mirror of science?

In chapter 3, Tabaczek offer a brief history of what philosophers see in the mirror of the world.

Well, Aristotle sees everyday people going about their business. The folk are not really engaged in looking in the mirror of philosophy.

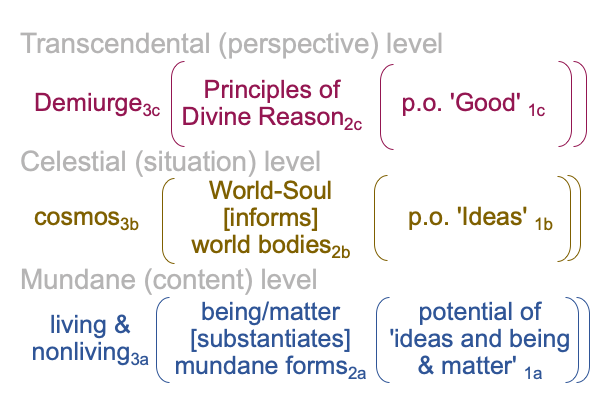

0294 Plato offers a more spectacular vision. Plato’s World-Soul strikes many contemporary agent-science theologians as an analogy of the God-World relationship. The World-Soul2 arises from the potential of matter entering into forms1 in the normal context of a cosmos-creating demiurge3. So, the World-Soul2 is like an Idea2 (with a capital “I”) or a Principle of Divine Reason2.

Do I have that correct?

0295 Let me try this again.

The World-Soul2c is a God created by a demiurge3c and expressing the principles of divine reason2c that emerge from (and situate) the potential of Good1c.

In the normal context of the cosmos3b, the world soul [informs] world bodies2b based on the potential of Ideas in the celestial realm1b.

In the normal context of our world of living and nonliving3a, being and matter [substantiates] mundane forms2a emerges from (and situates) the potential of the ideas of being and matter1a.

0296 The resulting diagram does not precisely follow Plato or Plotinus or Proclus, but it does capture some of their notions and stuffs them into slots of a three-level interscope.

0297 Does this look like a three-level interscope for emergent phenomena?

If so, then the emergent is World-Soul [informs] world bodies2b, which is contextualized by the perspective-level possibility inherent in Good1b.

How obvious is that?

Is this why Plato considers the world of forms as more real than everyday life?

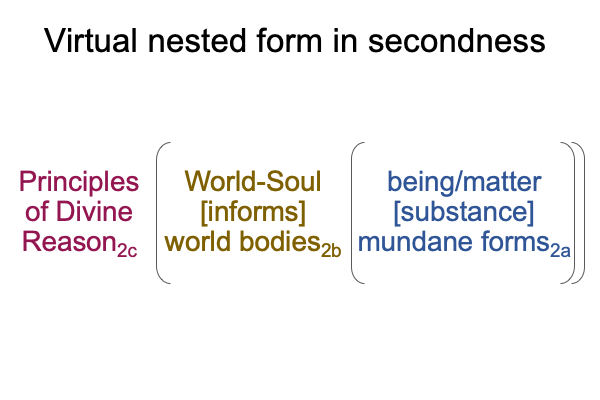

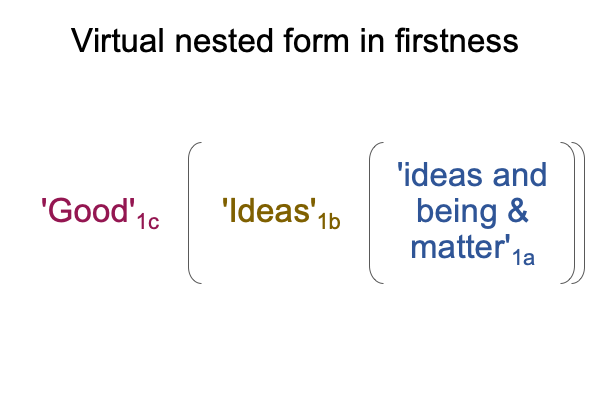

0298 Next, the reader should know the drill. Consider the virtual nested forms.

Here is the virtual nested form in the realm of actuality.

0299 The “downward causation” and the “dynamical depth” of Plato’s interscope is apparent in passage from perspective to content level actualities. The virtual nested form in the category of secondness descends from transcendent2c to celestial2b (or, at least big-picture) to mundane2a (or little picture). The transcendent2c sets the normal context. The celestial2b characterizes the actuality. The mundane2a associates to possibility.

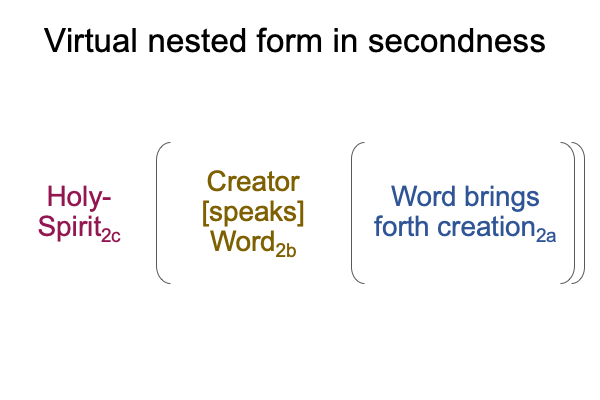

Perhaps, one of the reasons why Christian theologians find Plato is so attractive rests in certain relational (or metaphysical) similarities. Unlike other deities, the Christian God spans all three of Peirce’s categories. Expressions of the Christian God are diverse. Many of the expressions fit category-based nested forms. The following diagram shows the Trinity as portrayed in the first chapter of Genesis, corresponding to a virtual nested form in the category of secondness.

0300 An item by item comparison of these two virtual nested forms proves interesting.

For example, [informs] compares to [speaks].

To me, a comparison implies that world bodies2b do not indicate things2a, but rather the formulation of things2a, just as the Word2b is not creation, but the way that creation dynamically brings itself forth2a.

Of course, the fact that this example is interesting is a bit of a distraction. The big question is how one arrives at the virtual nested form in the category of secondess from the Creation Story in the first place.

Say what?

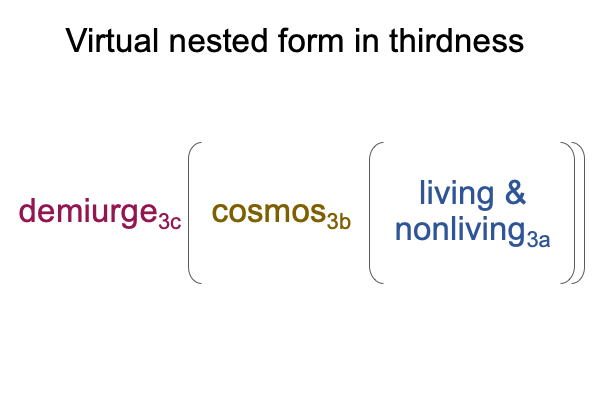

0301 Oh look, here is the virtual nested form in the realm of normal context!

0302 The logics of thirdness are exclusion, complement and alignment. One demiurge3c excludes all other demiurges. This implies that there is only one universe. Plus, the ruler of that one universe is responsible (puts into perspective) the celestial created order, the cosmos3b.

For the past century, the cosmos is “outer space”, a world that no one really worries about. Today, we know that the sun can launch a coronal mass-ejection capable of toasting modern electrical grids. So, the boundary between the cosmos and the mundane becomes more like the boundary between situation and content.

On top of that, our solar system has orbited the center of our galaxy only 18 times. Every orbit last several hundred million years. Every orbit is a blessing.

With that in mind, most everything that we worry about is on the mundane level. Plato wants us to broaden our view beyond our fixations on the living and the nonliving3a in order to come into harmony (or alignment) with the cosmos3band the creating demiurge3c.

Here is the virtual nested form in the realm of possibility.

0303 Needless to say, every one of these “words” are sites of contention in our current Lebenswelt. They are labels for entities that cannot be named in the Lebenswelt that we evolved in, yet nevertheless are real, because they are relational beings3a that we innately anticipate and seek1b because they are good1c. What glucose is to honey, good ideas are to our living being.

0304 Of course, Plato and Neoplatonism come long before the Age of Ideas. So, this general schema cannot be projected from one side of Tabaczek’s mirror to the other. The mirror has not yet differentiated.

One can say that Plato and the Neoplatonics are natural philosophers, so they represent what science-lovers might see in the mirror of theology, over two thousand years later.

0305 With this jump in mind, it is no surprise that Tabaczek next mentions German Idealism, a philosophical movement that blossoms a century after the mechanical philosophers wind up the alarm clock for the Age of Ideas and set the alarm for 400 years.

They set the alarm around 7400 U0′. The alarm goes off around 7800 U0′. See point 0231.