0640 Chapter seven discusses the systematic manipulation of the pillars of belief.

Stiles calls the process, “operation sheepskin”, in a tongue-in-cheek reference to various covert (yet, later disclosed) initiatives of the Agency of Centralized Intelligence.

As Stiles tells it, opportunistic manipulations of the pillars of belief are already ongoing at the end of the nineteenth century, as seen in the way that Southern Railroad covered the tracks of their systematic exploitations by paying for news stories that extolled their… um… reputation for honesty in commerce. Yes, that’s the ticket.

The press is compliant, because the ticket is where the money is. Plus, those who were systematically ripped off don’t have any money. Funny how it works that way. Heads I win. Tails you lose.

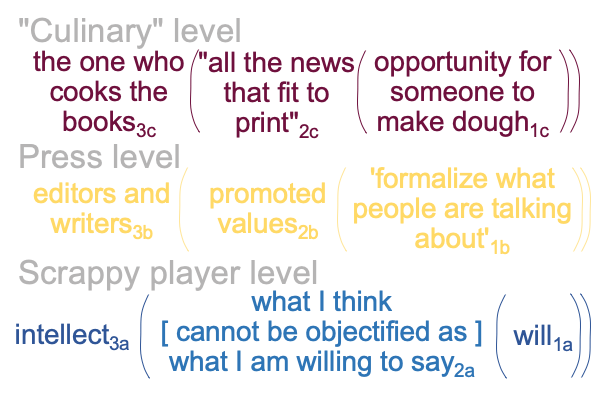

0641 Savvy observers in the late 1800s and early 1900s note the trend. These observers codify the techniques of crowd manipulation. The first step in crowd manipulation is to find a crowd. The second step seems to be, “Start a rumor.” Well, that sounds precisely the job for the newfangled newspapers printed on cheap paper. There is always someone who is cooking the books who will offer an opportunity for someone to make dough by publishing a story with a hidden agenda2c.

Of course, the reader who wants to be informed does not regard the hidden agenda. The reader sees all the news that is fit to print.

0642 Here is a picture of the post-truth interscope for the early 1900s. The details on the printed page are true, but the hidden agenda is not revealed. Indeed, if material that is intentionally omitted becomes available, then it becomes clear that a planted story has been… um… cooked up.

But, that does not change the newspaper’s slogan, “News that you can trust!”

0643 Clearly, at this time, the press reports news that people are interested in. After all, the main source of revenue for newspapers is subscriptions or people paying for a copy of the latest print. For the most part, editors and writers do not promote values that contest the values of the paying customer.

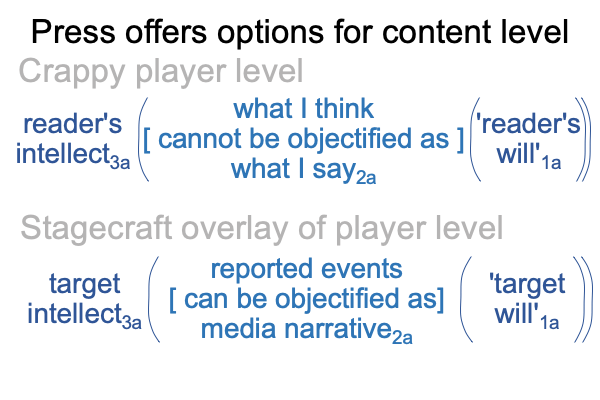

But, the “culinary customer”, you know, the one with dough, (as well as, a taste for manipulation and propaganda) savors the occasional foray into stagecraft. In stagecraft, the press reports an event that is designed to further a hidden agenda. In order to do so, the content-level of the newspaper’s reason3a,1a differs from the content-level reason3a,1a of the scrappy player, in such a way that the player’s reason3a,1a becomes a target for manipulation.

0644 Of course, if the crappy player replaces his own reason3a,1a with the targeted reason3a,1a provided by a press release, then what the crappy player thinks can be objectified as the media narrative that the crappy player recites.

May I call that replacement, “submission”?

Submission calls for recitation, while critical thinking calls for interpretation.

But, how can one interpret any newspaper report when information that does not conform to the media narrative is intentionally omitted?

That is what hidden agendas tend to do.

Hidden agendas hide information.

0654 One may wonder.

How far can this manipulation go?

That is the question that operation sheepskin intends to answer.