0954 What do humans need?

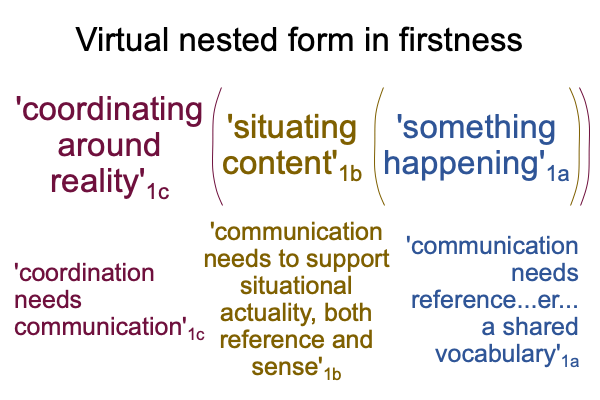

Well, if they are going to coordinate1c, then they need to communicate1b.

If they are going to communicate1b, then they need to make sensible sense2b of a referent2b.

If they are going to make sensible sense2b of a referent2b, then they need to have the same label1a for the referent2a.

If they are going to share the same label for a referent2a then they need to use spoken words2a.

0955 Why?

Spoken words are all we have.

This is the dilemma of our current Lebenswelt.

Spoken words are purely symbolic. They do not image or indicate their referents. They are labels. So, “communication” is all about the dynamics of sharing labels.

0955 Chapter six concerns communicative need.

In addressing the question of what humans need, answers track down the virtual nested form in the realm of possibility.

Here is a picture.

0956 Enfield tells of a magical moment when he is in a canoe with two village men, being transported down a river. One has to read Enfield’s text in order to appreciate the magic of the moment.

0957 I suppose that once, I also experienced a similarly magical example.

I have a friend with a precocious two year old, who learned that the traffic sign reading “Not A Through Street” means “Dead End”. While “not a through street” may be difficult to properly reference, “dead end” apparently is not. This tyke yells “Dead End”, again and again, whenever the car passes a “Not A Through Street” sign, because of some “communicative need”. Passengers not prepared for the display find it simultaneously humorous and disturbing.

What will this child grow up to be?

0958 Enfield wants to communicate one lesson. Since spoken words label only a fraction of things that can be labeled, then there must be a reason for why one spoken word exists while others do not.

I suppose the tyke in the above story has a reason for the display, which occurs with such an outburst of joy and excitement, that everyone in the car shares the revelry.

I know what that sign means!

0959 Enfield wants to communicate a second lesson which is even more notable. All cultures around the world are remarkably alike in what they do capture.

0960 And, that reminds me of a religion and science conference that I attended, where all the scientists naturally took their seats on one side of the auditorium and the religious folk congregated in the seats on the other side of the auditorium.

0961 Of course, I am not saying that Enfield’s discussion concerning the structure of the Kri and English languages does not follow a model where there is a trade off between communicative costs and cognitive costs. Nor am I saying that there is not an optimal frontier between having a vocabulary that provides more explicit information and takes more effort to learn as opposed to a vocabulary that provides less explicit information and takes (well, let’s be frank) less effort to learn.

However, I am wondering where the scientists and the theologians would place themselves in the spectrum of this optimal frontier.

0962 Of course, the scientists would claim the banner of the former, because scientific disciplinary languages provide very explicit information and take a lot of effort to learn.

At the same time, the theologians would not claim the banner of the latter, even though it is obvious to scientists that theological terms provide less explicit information and take less effort to learn.

0963 However, when it comes to theological subtlety, scientists find themselves clueless. After all, the notion that Stevie could use Mrs. Verloc’s hand in order to stab Mr. Verloc with a carving knife is outside the bounds of science. But, it is not outside the bounds of language and reality.

0964 Indeed, Enfield’s line of thought swerves after his scientific explanation, as if there is more to the optimal frontierthan a trade off between communicative and cognitive costs.

For example, the kinship terms of the Kri provide more detailed reference and are more difficult to learn because they aim not only to refer2a, but to impress2b. As such, my father’s older sister must be situated differently than my father brother’s wife. The kinship term for each2a must be “sensed” with the appropriate sensibility2b.

0965 In other words, a spoken label2a decodes into its referent2a and this referent2b is a clue that should overshadow sense2b.

This requires imagination1b.

At the end of chapter six, Enfield calls language, “a tool for the instruction of imagination.”

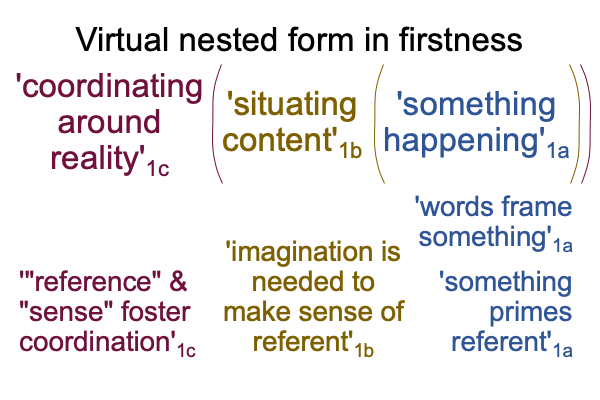

0966 Enfield’s admission bring me back to the virtual nested form in the category of firstness, appearing earlier.

The normal context of “reference” and “sense” fostering coordination1c brings the actuality that imagination is necessary for the referent to overshadow sense1b into relation with the possibility of ‘something’ that words frame and that primes words1a.