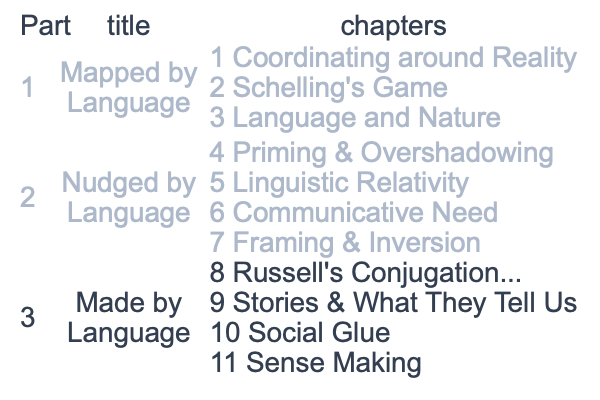

0996 By now, the partial character of the titles of the three parts should be apparent.

For each, the full title would include the prescript, “Reality Is”

So Part III is fully titled, “Reality is Made by Language”.

0997 The full title of chapter eight is “Russell’s Conjugation and Wittgenstein’s Ruler”.

In this chapter, Professor Enfield cuts a few jokes. He also mentions politics.

So, do not be surprised when I follow suit.

0998 The Russell conjugation is the first header in the title of chapter eight.

The Russell conjugation is a literary play on the conjugation of verbs in Latin and other romance languages. I love, you love and he loves. Well, the conjugation does not look impressive in English, but French and Spanish is a different story altogether. So, a prankster comes up with a play that mimics conjugation and appeals to British humor.

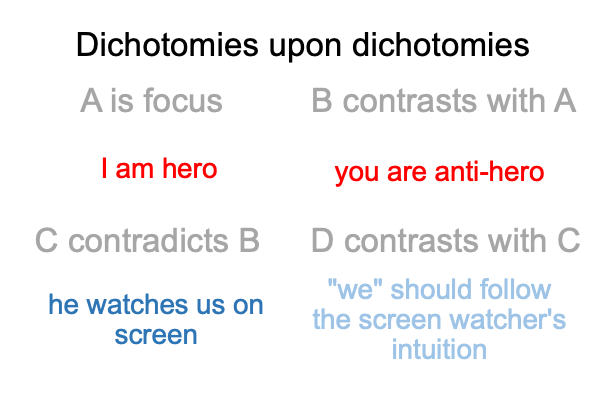

I am hero, you are anti-hero and he watches us on screen.

0999 My example of the Russell conjugation plays on two dichotomies. The first dichotomy is between hero and villain. The second is between actor and viewer. The two dichotomies seem to both apply to the same reality. What is that reality? The movies? Theater? Politics?

On top of that, the fact that there are two dichotomies but only three elements in the conjugation suggests that there is a missing term.

1000 That brings me to the Greimas square. The Greimas square is invented by a linguist. The Greimas square is a purely relational structure. There are four elements corresponding to four corners of a two-dimensional box. The first dichotomy occupies the upper two corners, A and B. The second dichotomy occupies the lower two corners, C and D.

There are rules. A is the focal term. B contrasts with A. C speaks against B and complements A. D contrasts with C, speaks against A and complements B.

1001 Here is the Greimas square for the example.

1002 Yes, the Greimas square is a purely relational structure congruent with the purely relation structure of language. Once rendered as a Greimas square, the Russell conjugation is actually an instruction to an audience. Follow the intuition of the person, “he”, watching “me” and “you” on screen.

The ancient Greek chorus is an early instance of this “he” in theater.

1003 The Greimas square appears in many of Razie Mah’s blogs in 2023. Look and see.

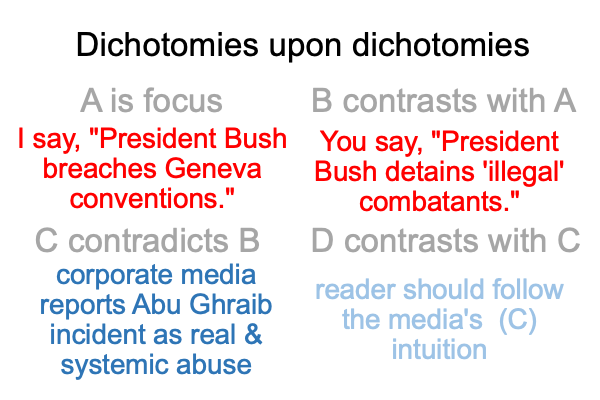

1004 The Russell conjugation morphs to “I say, you say, he says” in the following political example.

1005 Curiously, the Abu Ghraib story appears on page 128 (at the very start of Part III) and again on page 198 (at the end of Part III).

1006 One of the rules of thumb for reading philosophy texts is to look around the middle of the book for an esoteric message. Also, look for topics that get revisited later.

Remember Schelling’s games of coordination? The same applies to philosophy books.

Typically, philosophy texts are full of exoteric messages, from beginning to end. So, a good hiding place for an esoteric treat resides right in the middle of the book. Another hiding place is split into two locations.

Applied here, the rule of thumb says, “When you encounter an incident on page 128, and again on page 198, then be aware that it may be an esoteric message.”

The rule is fulfilled by Enfield’s split reflection.

1007 To me, this philosophical treat consists in comparing the passages concerning Abu Ghraib on page 128 and on page 198, side by side. The comparison highlights the manipulative genius of Russell’s conjugation.

There is more to Russell’s conjugation than meets the eye.