1020 What does this imply?

Can I replace the content-level potential with the noun, “agreeability”?

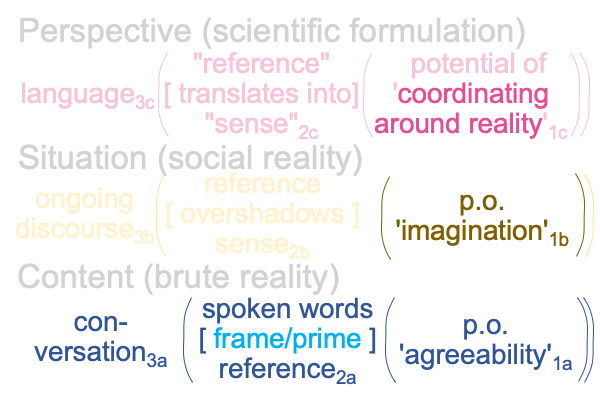

The normal context of everyday conversation (as well as anything approaching conversation)3a brings the actuality of spoken words [framing and priming] reference2a into relation with the potential of agreeability1a.

1021 So, the content-level question, “What is happening?”3a, is answered.

The potential of ‘something’ happening1a is also addressed.

1022 Speaking of ‘something happening1a, I wonder, “What question does the potential of agreeability always avoid?”

1023 Does Eve ask the serpent, “Why would you lie to me?”

And, if she did, would the serpent have replied, “Why are you so disagreeable, today?”

This brings me to the second header in the title of chapter eight: Wittgenstein’s rule.

1024 Wittgenstein’s rule is deceptively straightforward.

A speaker’s statement may tell the listener more about the speaker than what the speaker is talking about.

So, if the speaker’s motives are nefarious, then what the speaker is talking about could be misleading.

1025 Why is Wittgenstein’s rule deceptively straightforward?

It’s like telling someone that the way to get from the house to the bakery is to fly.

People don’t fly.

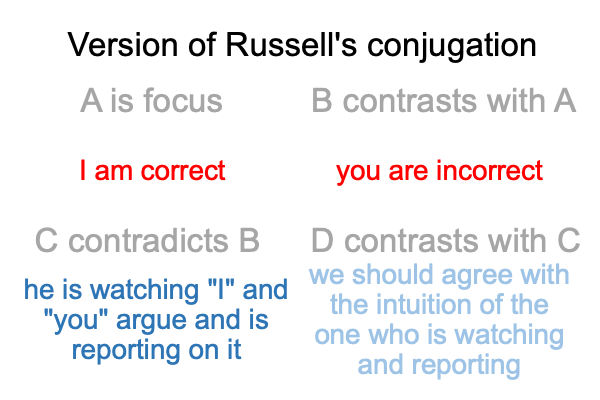

1026 Here is the Russell conjugation-inspired Greimas square for an argument between I (A) and you (B) that is being watched and reported on by he (C).

Now, how does Wittgenstein’s rule fit into this picture?

Oh, it fits in as the contrary of D.

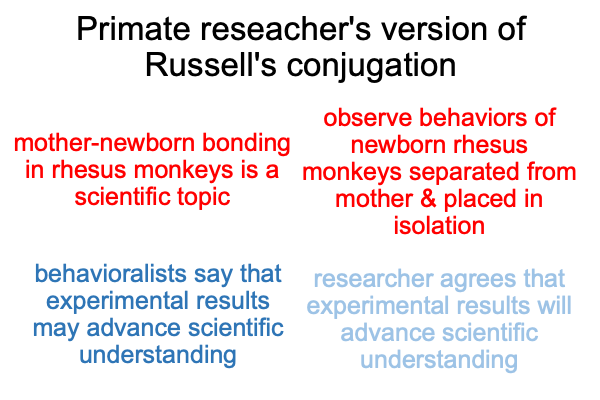

1027 Here is another example.

In the introduction, Enfield mentions the sad tale of primatologist, who becomes a research scientist during the heyday of behavioralism. The behavioralist treats the subject of inquiry as a black box.

The idea is to scientifically control the input that an animal receives and observe the animal’s behavior in response to the researcher introducing controlled input.

In order to study mother-newborn bonding in an animal model, this researcher follows a protocol that separates a newborn rhesus monkey from its mother and places it in an enclosure where inputs can be rigorously monitored.

He does this for years because behavioralists say that the results of these types of stimulus-response experiments will advance scientific understanding.

1028 Of course, the primate scientist agrees.

1029 Where does Wittgenstein’s rule fit into this picture?

Oh, it fits in only insofar as its violation explains the researcher’s inability to notice1b that all the rhesus monkeys under investigation are suffering horribly.

So, without the primatologist even knowing it, the researcher’s publications tell us more about the agreeability1a of the scientist than the actual results that are contained in the publications.

1030 Uh, I suppose that the last sentence restates Wittgenstein’s rule.

1031 Which only goes to show the value that this examination adds.

I have demonstrated that, since we evolved to be agreeable1a, we are unable to follow Wittgenstein’s rule.

1032 But, there is a bright side.

After our inability to follow Wittgenstein’s rule leads to a nightmare so horrible that we could not have foreseen it, a Gestalt switch gets thrown.

Our imagination1b transforms and we come to realize that Wittgenstein’s rule applies.