0001 In 2017, the author publishes a book, in Polish, with the English title, “The Metaphysics of Relation: At the Basis of Understanding the Relations of Being”. This article slices out one topic among many.

Thomas Aquinas uses the Latin term, relationes secundum dici, in ways that lead to a variety of interpretations. Consequently, the complete title of this work is “The Specificity of Secundum Dici Relations in St. Thomas Aquinas’ Metaphysics”. The article appears in Studia Gilsoniana 12(4) (October-December 2023), pages 589-616.

0002 I know that this article is scholarly, because the summary (abstract) appears at the end of the text.

0003 Why does this article capture my attention?

The term translates into relations (relationes) according to (secundum) speech (dici)… er… talk (dici).

I don’t think the Romans have a word for forms of talking other than speech.

They are so civilized.

0004 The term applies to various questions, such as when a pagan calls his god, “Lord of the heavens”, as well as the relation between matter and form, the relation between accident and substance, qualities of things, one’s orientation in labeling one side of an auditorium “right” or “left”, and so. These are just samples. Duma presents five cases in detail.

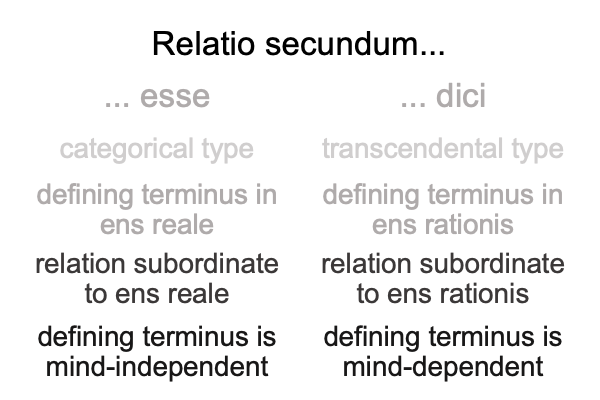

0005 The dici term contrasts to a similar term, relationes secundum esse.

The latter translates into relations (relationes) according to (secundum) existence (esse)… er… esse_ce (esse).

Esse_ce?

Esse_ce is a written play on the Latin term, esse.

Esse_ce is the complement to essence.

Whatever has esse_ce also has essence. Whatever has essence also has esse_ce.

0006 Those two statements sound like relationes secundum esse even though they may be relationes secundum dici.

Why?

The relation between esse_ce and essence is another way to state the relation between matter and form.

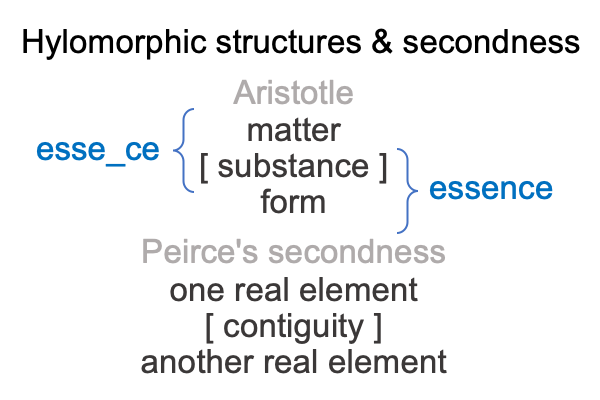

0007 Plus, the relation between matter and form is an exemplar of Peirce’s category of secondness, the dyadic realm of actuality (that contrasts with thirdness, the triadic realm of normal contexts, and firstness, the monadic realm of possibility).

Secondness consists of two contiguous real elements. For Aristotle’s hylomorphe, the real elements are matter and form. The contiguity is not named. However, a name stands ready-at-hand. That name is “substance”. So, I can take the word, “substance”, and place it in brackets (for notation), to arrive at the following figure.

0008 Now, my interest in Duma’s article begins to clarify.

The relation between matter and form is a relation where the terminus of the relation is a word, so to speak, that denotes either the presence (matter) or the shape (form) of a thing. But, it does not denote a thing (which expresses both esse_ce and essence).

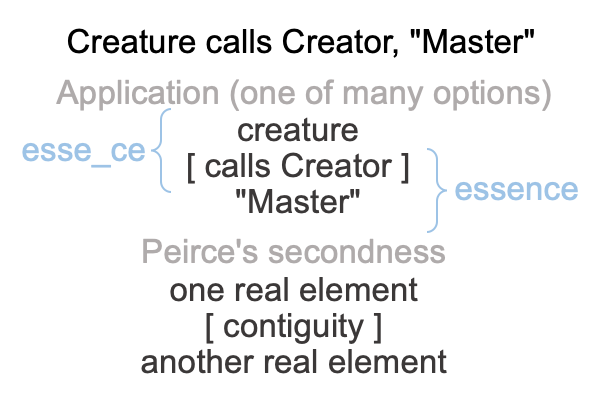

The same goes for the creature calling his creator, “master”.

When I watch the ritual proclamation, I encounter two real elements, the creature and the proclaimed word. I must figure out the contiguity between these two real elements. Both real elements are locked in a literal relationes secundum dici (a relation according to talk).

So, I place my guess into the slot for contiguity.

0009 Because Aristotle’s hylomorphe is a premier example of Peirce’s secondness, the creature [calling Creator] aspect of the dyad carries the feel of matter [substance], esse_ce, or “existence”. Also, the [calling Creator] “Master” aspect carries the feel of [substantiating] form or essence.

May I go as far to say that much of Aquinas’s philosophy carrries the feel of matter [substance] form, even as Aquinas transcends the esse_ce and essence of Aristotle’s philosophy in an intellectual flight towards a recognition that is so… so… divine?

God is Substance.

God is the contiguity between all real elements in Peirce’s secondness.

0010 According to John Deely’s massive book, Four Ages (2001 AD), Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) is an important waystation between St. Augustine (354-430), who poses the question of sign-relations, and John of St. Thomas (John Poinsot (1589-1644)), who finally and correctly identifies signs as triadic relations.

Aquinas mentions relatives in his discourses on various theological and philosophical questions and disputes. The diciand esse relations stand out. They are are similarly worded. The formula is relationes secundum X, where X is either esseor dici. Esse relations pose few difficulties. Dici relations lead to confusion and debate.

0011 Here is a table listing some of the characteristics of each.

0012 In this examination, I have already brought Duma’s article into relation with one aspect of Peirce’s philosophical schema.

I hope that no one is surprised.

The next step adds another layer and that may take the reader off guard.