0056 In the laboratory sciences, an experimental recipe allows the student to observe and measure phenomena that validate the model (overlaying the noumenon).

In biosemiotics, S&T’s noumenal overlay serves as a template for students and researchers. Phenomena, corresponding to certain (real) elements, may be observed and measured in order to elucidate mechanistic models for the elements that constitute the contiguities. In short, the mechanisms for the science beyond natural science consider phenomena that incorporate Aristotle’s formal and final causalities to be observable and measurable facets of S&T’s noumenal overlay. Consequently, biosemiotics is not philosophically impoverished.

0057 Does S&T’s noumenal overlay correspond to the propositions of a “New Mechanistic Philosophy” that have been floating around since around 2000 AD?

Yes, S&T’s noumenal overlay applies to structures that perform a function by virtue of their participation as a component in a larger operation. In the example, being awake functions as a platform for the operation of conscious activities. Function associates to salience.

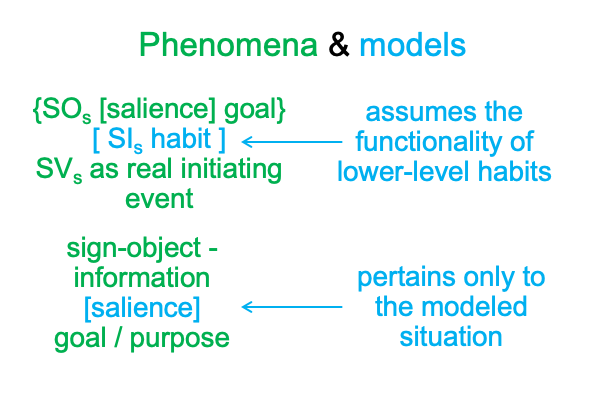

No, S&T’s noumenal overlay does not reduce higher-level phenomena to the dynamics of lower-level components,except in so far as failure of lower-level components may trigger failure of higher-level components, leading to systemic failure.

0058 After that curveball, what about the idea of information?.

May I substitute the term, “information” for “object (SOs)”?

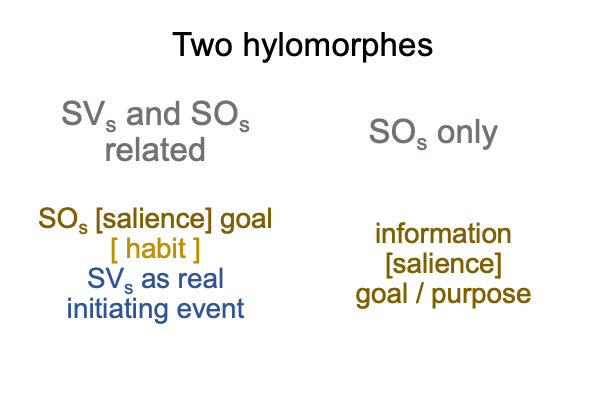

If I do so, then I get two hylomorphes that look fairly independent, even though they are actually embedded, one within the other.

0059 What are the advantages of Sharov and Tonnessen’s noumenal overlay?

Well, first, for the natural sciences, noumena are recognizable things. Such is the advantage of the label, “noumenon”. The thing itself cannot be objectified by its observable and measurable facets because the noumenon should be obvious. If it is not so obvious, then it must be pointed out. To me, agency seems intuitively obvious. At the same time, one cannot picture or point to agency. The term is an explicit abstraction, leading to Kull’s criteria and similar proposals.

Second, for biosemiotics, semiotic agency manifests a sign-relation. Sign-relations are intuitively obvious, but one cannot paint or tag a sign-relation. In order to make the sign-relation an actual thing, the authors render a dyad, derived from the two-level specifying sign-relation. The dyad is a diagram that pictures the specifying-sign relation as an actuality.

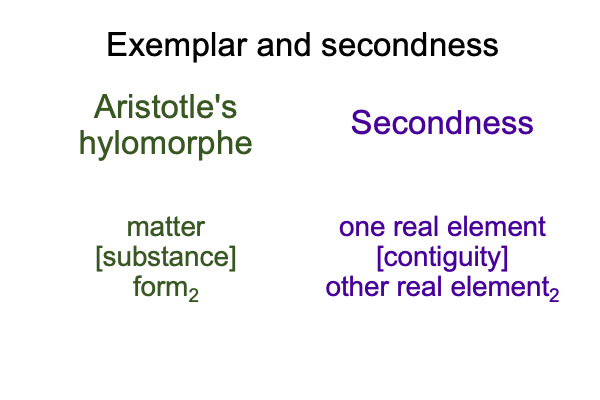

For Aristotle, the dyad of matter and form constitutes the first step of philosophical abstraction. See Comments on Jacques Maritain’s Book (1935) Natural Philosophy. For Peirce, the category of secondness, the realm of actuality,consists in two contiguous real elements.

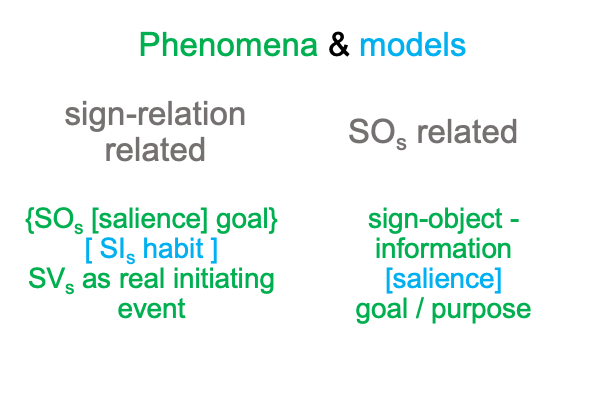

0060 Third, the S&T noumenal overlay more or less breaks down into elements that associate to phenomena and elements that need to be accounted for by models.

0061 How about validation?

Does this dyad integrate semiosis with mechanism?

In section 1.4, the authors offer principles for integration.

The question is whether this dyad satisfies those principles.

0062 The first principle?

According to anthropologist and semiotician, Gregory Bateson (1904-1980), a sign is a difference that expresses a difference.

Does S&T’s noumenal overlay match this statement?

0063 Note how Bateson mentions two differences.

The first difference is the difference between the SVs and all other potential significations. Somehow, to an agent, the SVs stands out. Well, it stands out because the SVs “causes” (through habit SIs) a SOs. Or is it the other way around? Does a SOs make a SVs more likely to be noticed?

The SVs associates to form (for Aristotle’s hylomorphe) and effect (for a standard configuration of Peirce’s secondness). The SVs stands for a SOs in the same way that a form can stand for its matter. The SVs is like a form that conjures the matter that substantiates it. The SVs is like an effect that prompts its cause. So, the first difference is counter-intuitive, especially for the Aristotelian and the philosopher who imagines that cause precedes effect. Sign-relations do not easily break down into causes and effects.

0064 The second difference occurs within the SOs. Now, within the SOs, a sign-object [substantiates] a goal. This substance characterizes a second dyad, corresponding to the sign-object serving as information substantiating a purpose. So, the second difference is between two contiguous real elements: information and intention. The substance may now be labeled with the term, “salience”.

Bateson’s definition of sign is satisfied.

0065 The second principle for integrating mechanism and semiosis is that a sign-relation may be regarded mechanistically.

Sharov and Tonnessen’s noumenal overlay fits the second principle in so far as the contiguities are subject to models. The biosemiotician models [habits] and [salience].

0066 The third principle is that lower-level agencies are relied upon by higher-level agents.

S&T’s overlay satisfies this principle in the following manner.

0067 The fourth and final principle?

Mechanistic and semiotic analyses complement one another.

The complementarity between dyadic mechanistic formulations and triadic semiotic structures is obvious in S&T’s noumenal overlay.