0068 Now, I wrap up chapter one, by returning to the nature of science as two interlocking judgments.

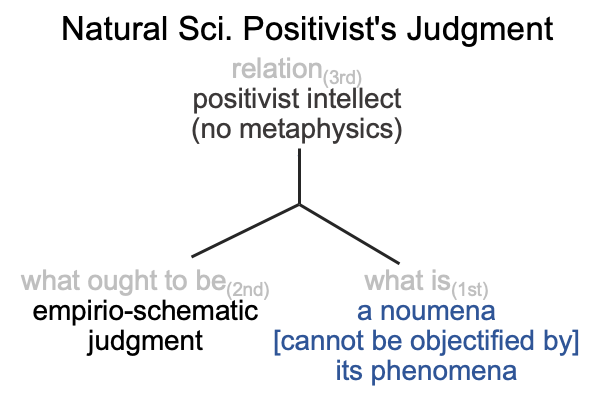

The Positivist’s judgment originally applies to the natural sciences. By the time that Kant articulates his position (that the noumenon cannot be ignored), physics and chemistry are speedily developing. Biology is not far behind. The social sciences are already exercising empirio-schematic judgments, even though noumena for the social sciences are not as obvious as noumena for the natural sciences.

0069 Does the Positivist’s judgment make sense?

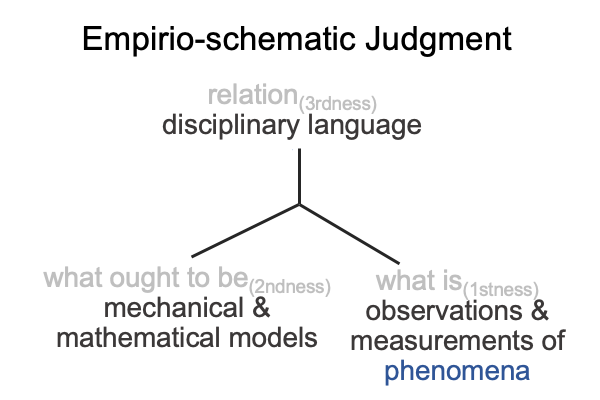

Yes, as far as scientists are concerned, the empirio-schematic judgment (what ought to be, secondness) defines the operation. Disciplinary language (relation, thirdness) brings mathematical and mechanical models (what ought to be,secondness) into relation with observations and measurements of phenomena (what is, firstness). Models are a source of illumination for scientists.

No, as far as philosophers are concerned, what is for the Positivist’s judgment potentiates the operation. But, there is a problem.

0070 Why doesn’t a noumenon [&] its phenomena belong to the category of secondness, rather than firstness?

Secondness consists of two contiguous real elements. Secondness is the dyadic realm of actuality. Matter and form belong to one thing. They are two real and distinct elements. So, theoretically they are independent. Matter [substantiates] form.

In contrast, what is for the Positivist’s judgment is assigned to the category of firstness. Firstness is the monadic realm of possibility. This implies that the two real elements cannot exist independently. In other words, there is no noumenon without its phenomena and there are no phenomena without their noumenon. The noumenon is the thing itself. Phenomena are its observable and measurable facets. They are the same thing.

But, they are distinctly different aspects of the same thing. A noumenon [cannot be be objectified as] its phenomena.

0071 For example, consider a coin.

For Aristotle, the matter of a coin is (presumably) a precious metal. The form is the stamped shape. Matter and form are real (and independent) elements. The coin belongs to secondness, according to Aristotle.

For the Positivist’s what is, the noumenon of a coin is the thing itself. Its phenomena consists of the stamped impression, its standard weight, its standard metallic composition, as well as other observable and measurable facets. Do phenomena also include how people handle coins? Is how people handle coins an observable and measurable facet of the coin itself?

What is going on?

Is the Positivist asking the Aristotelian for the coin that he is holding, in order to ascertain whether he can detect some phenomena related to this noumenon?

What is he providing in return?

Oh, the Positivist is going to provide a data-driven mathematical model that is as actual (imbued with secondness) as what the Aristotelian regards as matter [substance] form.

I suppose that is worth the price of the coin.

0072 Okay, what about the transactional value of the coin?

For Aristotle, the transactional value is the coin’s formal cause. The intended use of the coin for transactions (and for storing value) are the coin’s final causes. These formal and final causes belong to the category of firstness, the realm of possibility. So, for all practical purposes, the Aristotelian philosopher focuses on the noumenon, as the source of illumination.

For the Positivist’s what ought to be, models of transactional value explain how people respond to the noumenon, the coin, through use in transactions and in storage. In the empirio-schematic judgment, the disciplinary language of economics (relation, thirdness) brings mathematical and mechanical models (what ought to be, secondness) into relation with observations and measurements of the way people handle money (what is, firstness),

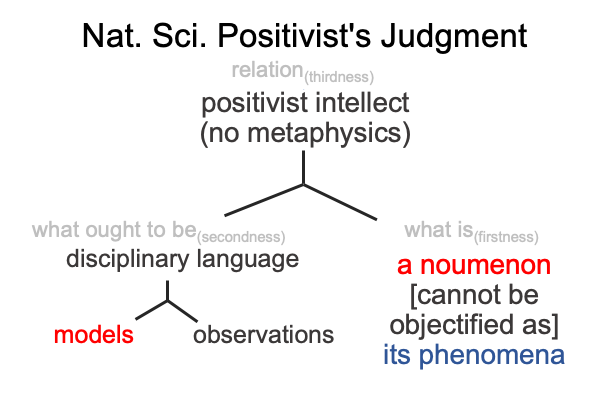

0073 Clearly, the scientist adopts the Positivist’s judgment in order to construct models as real sources of illumination. These models exclude formal and final causation. The positivist intellect excludes metaphysics. Consequently, all the formal and the final causes within the Positivist’s judgment get shoveled into the noumenon, then ignored, since the noumenon cannot be objectified as its phenomena.

0074 In the following figure, the two sources of illumination are painted red.

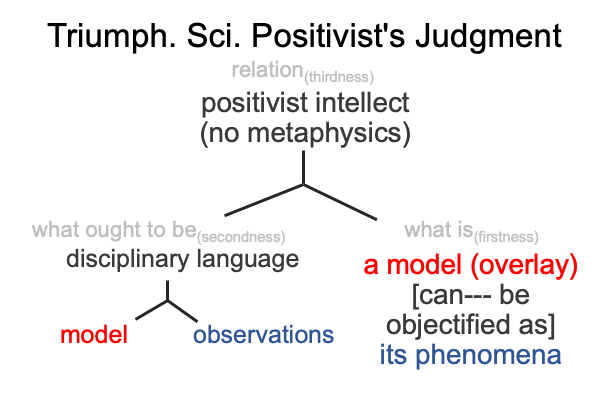

0075 So, what does the triumphalist scientist do?

Well, in academic laboratory sciences, triumphalist scientists place the model as an overlay for the noumenon.

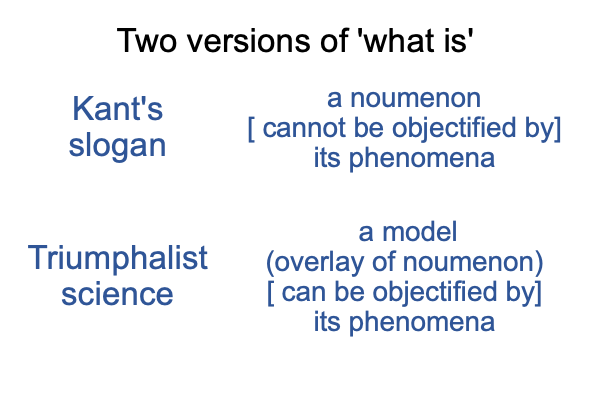

In this way, a triumphal natural scientist can resolve the antithesis embedded in Kant’s slogan. The model (overlaying the noumenon) can be objectified as its phenomena.

0076 Here is a comparison.

0077 While the reader may think that the triumphalist scientist’s trick for getting around Kant’s slogan may not be legitimate, the substitution provides a curious opportunity. If a natural scientific model serves as a noumenon, then the observable and measurable facets of that noumenal overlay may serve as phenomena for another exercise of the empirio-schematic judgment. A change in what is, for the Positivist’s judgment, provides new material for what ought to be. In this case, what ought to be supports academic educational laboratory sciences.

The challenge for the laboratory sciences involves a search for experimental phenomena that clearly, safely and conveniently objectify their model (noumenal overlay).