0087 Rene Descartes and Immanuel Kant are discussed in sections 2.2 and 2.3.

0088 Descartes is considered to be one of the great mechanical philosophers of the 17th century. He invents a tradition that becomes capable of substituting mathematical and mechanical models for the thing itself.

Weirdly, triumphalist natural science makes the noumenon superfluous.

That brings me to the metaphor of the leaf as a site for a type of inquiry that makes the tree of semiosis invisible. I pull a leaf off the tree of semiosis, examine it carefully, and realize that it only proposes a mechanism that substitutes for the thing itself.

Does the tree of semiosis even exist?

Where do all these leaves, like ink-filled pages in academic journals, come from? All I read about are observations and measurements of phenomena, as well as the mathematical and mechanical models that account for them. Sheaves of leaves, all detached from… what?

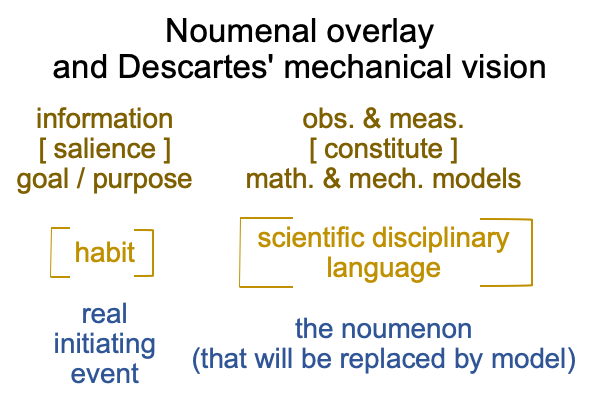

0089 Well, from prior discussion on the nature of the Positivist’s judgment and the empirio-schematic judgment, I may construct the following association between Sharov and Tonnessen’s noumenal overlay and Descartes’ triumphalist scientific paradigm.

It is just a guess.

0090 What about Descartes’ mind-body dualism?

Well, what if the noumenon is a wish?

Does the term, “wish”, associate to the mind or the body?

If wish (noumenon) associates to the mind, and if the observable and measurable facets of my wish are my choices (phenomena), then I can construct a model based on my bad choices that does not blame my conscious self (er…. “mind”) but rather my unconscious self (er… “body”).

Oh, that takes me back to Sigmund Freud.

0091 Now, I am not claiming that Freudian psychoanalysis is an exemplar of Descartes’ mind-body dualism.

My claim runs on a different set of tracks.

The locomotive manifests the power to move its body-cars and authorizes its own mission for why the cars are in the train.

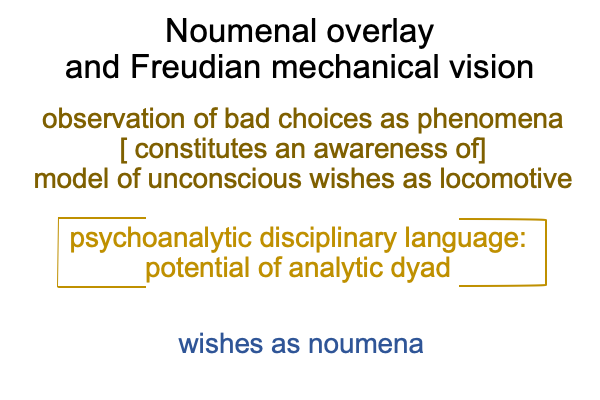

As soon as the inquirer replaces the psychoanalytic noumenon, with a model of an unconscious locomotive, pulling the body along like a train and justifying itself to the mind, then the analytic dyad becomes the method by which a client comes to awareness of what drives unconscious wishes.

0092 Let me say that again.

What do the above figures imply?

Initially, conscious wishes constitute the real initiating event (SVs) for this noumenal overlay.

0093 As soon as I commit an act of triumphalist science and replace the conscious wish with an unconscious one, then Freud’s schema detaches from the S&T noumenal overlay.

Unconscious wishes are models that replace conscious wishes as the noumenon.

Bad choices serve as phenomena that can be observed and measured. Observations of bad choices support models for how a locomotive for unconscious wishes both pulls the body along, like cars on a train, and justifies its own existence because the cars on the train must be going somewhere important.

The Freudian “driver of unconscious wishes” paradigm enters into Sharov and Tonnessen’s dyadic noumenal overlay as the source of real initiating events (SVs) and then is objectified by bad choices (SOs).

The real initiating event (SVs) no longer consists of conscious wishes, but unconscious ones.

At this moment, the psychoanalyst lets go of the tree of semiosis because the locomotive-model (as noumenon) now generates real initiating events (SVs) that stand for bad choices (SOs).

The client now must learn how to place the locomotive on a track that produces less bad or maybe even good choices.

0094 In short, as soon as the triumphalist psychoanalyst claims the prize and places the locomotive-model in for the noumenon, the subject of inquiry changes to one that a biosemiotician is no longer interested in. The real initiating event2a is produced by a locomotive of desire, as if this hypothetical construct is a disembodied mind.

Okay, maybe the substitution of a locomotive model for the real initiating event2a would create a subject of inquiry that a biosemiotician might be interested in.

Shall we ask what the locomotive has to say?

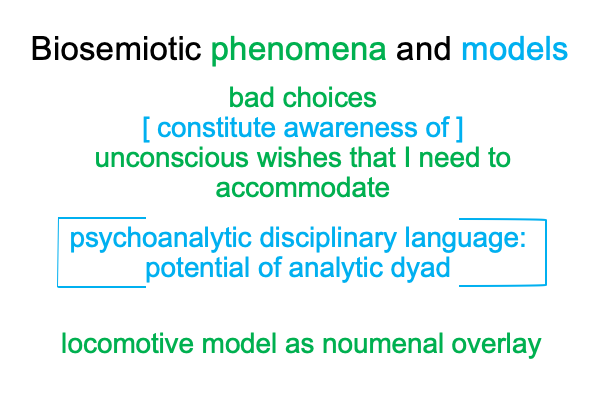

0095 Sharov and Tonnessen’s noumenal overlay allows me to see how the character of biosemiotic models changes within the milieu of psychoanalysis.

What else have I learned?

Biosemiotic models primarily account for the habit of the major dyad. Psychoanalytic disciplinary language and the potential of the analytic dyad correspond to self-governance and the potential of courses of action.

Biosemiotic models secondarily account for the salience between bad choices (as observed phenomena) and attributions to a locomotion of unconscious wishes (as a source of phenomena).

0096 The primary biosemiotic models may be abbreviated with the term, “habit”.

The secondary biosemiotic models are a little more slippery. The resonant dyad associates with the matter of semiotic agency and may be abbreviated with the term, “choice”.

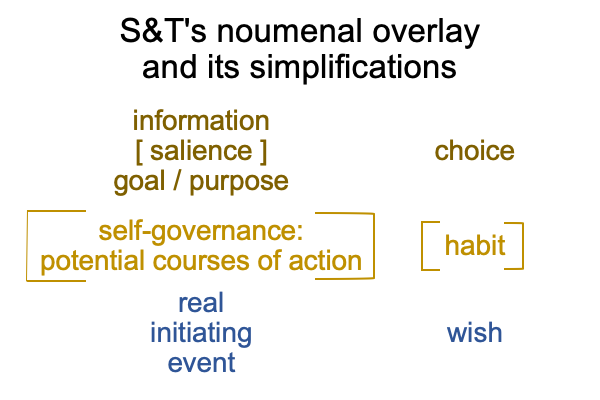

Here is a picture of Sharov and Tonnessen’s noumenal overlay, which has proved surprisingly adaptable so far, greatly simplified.