0115 Section 2.5 considers the non-mechanistic approaches of the American pragmatist, William James (1842-1910), and French philosopher, Henri Bergson (1859-1941).

These thinkers reject fully mechanistic models.

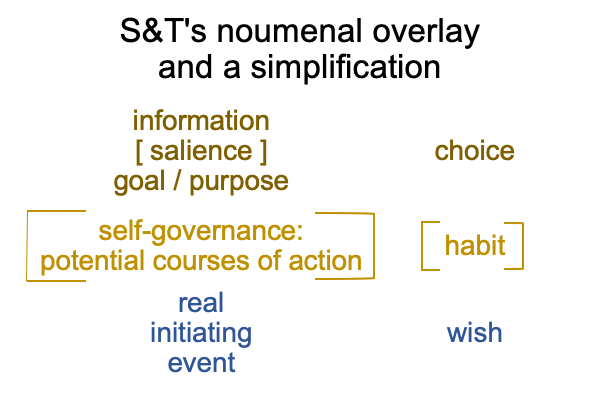

Do their ideas cohere to Sharov and Tonnessen’s noumenal overlay?

0116 For example, James considers consciousness. Consciousness is a state of semiotic agency.

This makes sense.

0117 Here is another option.

If one reduced the noumenal overlay of “consciousness” to a model of one specific type of incident where a real initiating event (such as a subject encountering loaded options provided by a state-empowered ideological agent) determines the same choice (regardless of the diversity of the human subjects), then a mechanism (the option preferred by the empowered agent is the “better” option) may be said to be a correct model. Afterwards, this “successful” modelmay be placed over the noumenal overlay of “consciousness”. Choice is habitually following the wishes of an ideological agent.

0118 This makes no sense at all.

Why?

The subject (human) lacks semiotic agency (the topic introduced in section 2.6).

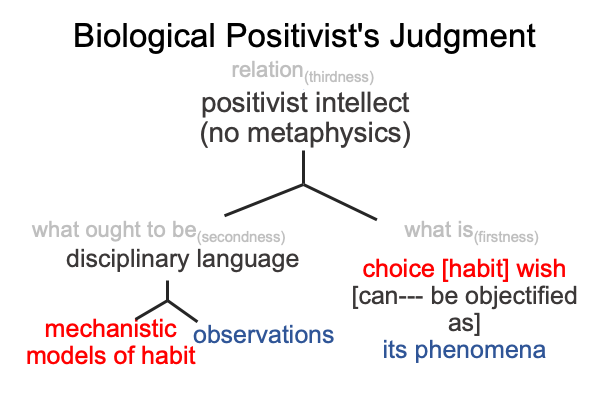

0119 But, what if the intellects of the time (say, around 1900) say that the subject has agency in way of choice [habit] wish. What if choice [habit] wish establishes a conceptual apparatus that can substitute for S&T’s semiotic agency as a noumenal overlay?

Then, is “consciousness” still relevant?

Sure, James and Bergson say so. But, where are the mechanistic and mathematical models that are the fruits of the Positivist’s judgment when “consciousness” is positioned as the noumenon for human agency?

0120 Is this where phenomenology comes in?

Phenomenology is the topic of section 2.7.

0121 Razie Mah offers a series, titled “Phenomenology And The Positivist Intellect”. E-articles within the series are available at smashwords and other e-book venues. The present blog fits nicely into this series, because… well… wait and see.

Sharov and Tonnessen’s book, Semiotic Agency, brings up the issue of phenomenology in section 2.7 and develops the theme of phenomenology in chapter 9.

So, section 2.7 is an introduction.

0122 I have already set a civilizational scene that draws phenomenology onto the stage as an actor who is trying to deal with the way that a theoretical construct that seems to be a mechanistic model (such as Spencer’s evolutionary vision as the dyad, choice [habit] wish) gets overlaid onto biological noumena and then is objectified by phenomena supporting empirio-schematic models that treat humans, not as semiotic agents, but as machines that validate the noumenal overlay.

0123 But, Spencer’s evolutionary vision is not a mechanistic model, even though it appears that way to the triumphalist biologist. Rather, it is a declaration of what the noumenon should be for the evolutionary sciences.

Plus, it is a simplification of Darwin’s two-level interscope, re-configured in the style of S&T’s noumenal overlay (points 107-112).

The resulting phenomena support observations when wishes and choices are experimentally controlled. After crunching the data, scientists offer a mathematical or mechanical model that characterizes the habit.

When applied to humans as biological subjects, the Positivist’s judgment does not make sense.

Human semiotic agency becomes a black box, to be replaced by a successful mathematical and mechanical model based on phenomena arising from the controlled initiation of wishes and the detached observation of choices.

Does this makes sense?

If phenomena are the observable and measurable facets of a noumenon, and if the noumenon is choice [habit] wish,then occasions of choices and wishes, even though metaphysical (in Aristotle’s sense of the term) must be classified as phenomena.

Humans are capable of observing and measuring these phenomena, because the tools to do so are innate.