0346 Then what happens?

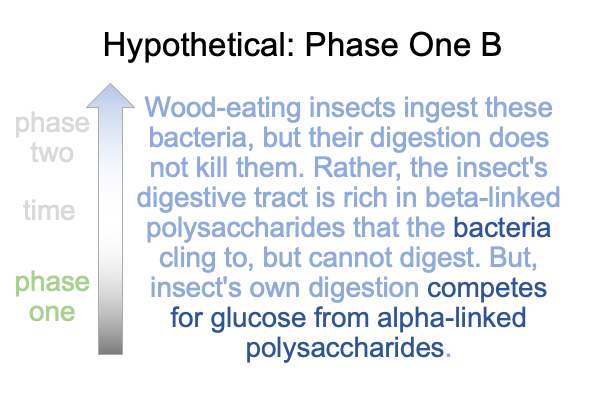

Wood-eating insects, who create the damage that attracts the cellulose-clinging bacteria, inadvertently ingest these bacteria, who do not create the damage that nourishes them. Bacteria are only present to exploit a long-established relation between exposed cellulose and food.

So, when a cellulose-clinging bacteria gets ingested, it can serve as food for the termite (if it dies) or it can simply pretend that nothing significant has changed (if it lives). Bacteria can still hold onto cellulose in the termite’s gut and compete for food with the termite’s own digestive system.

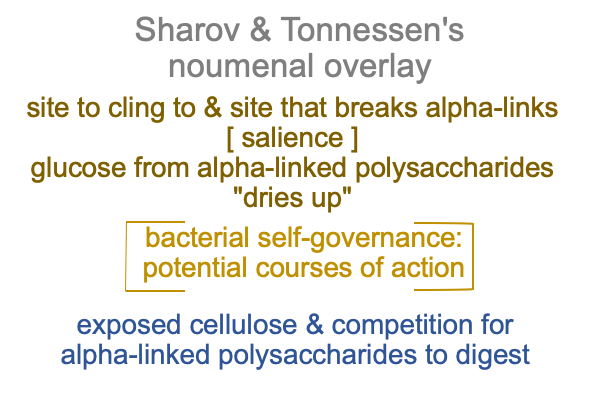

0347 The bacteria’s competition with the termite’s own capacity to digest alpha-linked polysaccharides presents a signaling error. It is as if exposed cellulose (SVs) no longer indicates that food is in the vicinity (SOs) according to the ways that this bacteria interprets the world (SIs).

0348 The specifying sign-relation fails because the bacteria clings to cellulose inside the wood-eating insect’s gut, but this no longer indicates that alpha-linked polysaccharides are available for food.

0349 Then what happens?

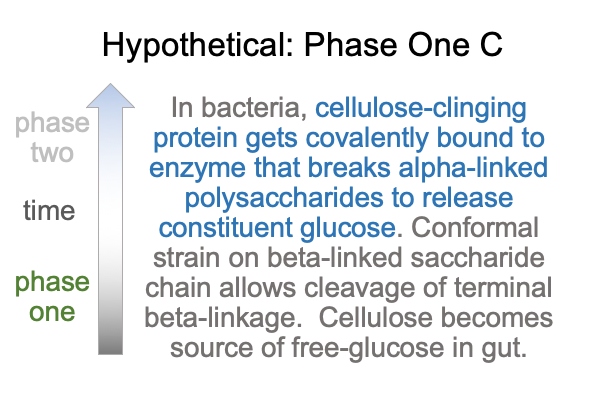

Well, phase one ends in this hypothetical scenario when the two independent biomolecular capacities that are innate in the bacteria, the ability to latch onto cellulose and the ability to cleave glucose from alpha-linked polysaccharides, get bound to one another. Now, a beta-linked polysaccharide chain may be held by the latching molecule and be conformationally distorted enough that a terminal glucose can be cleaved by the original cleaving enzyme.

0350 The bacteria lives off some of the glucose that it liberates. But, the potential source of glucose has changed from the starchy alpha-linked polysaccharides that both insect gut and bacteria digest to include previously undigestible beta-linked polysaccharides now available to the bacteria. Indeed, the bacteria release more glucose into the gut than what is available from alpha-linked polysaccharides.

The insect already has pathways for transporting glucose from the gut to the body.

The insect uses the free glucose for its own metabolism. All it needs to do is eat more wood and keep transporting liberated glucose out of its gut, so there is no build-up of soluble glucose in the gut and the bacteria keep that beta-link cleaving pathway operating.