0499 So, I can look at the paramecium in the petri dish, the subject of my biological inquiry, and wonder, “What would I do if I were that poor thing?”, before releasing a small drop of nicotinic acid in its vicinity.

0500 If I had a more powerful microscope, then I could gaze upon the creature portrayed in Figure 10.1 of the text, and wonder whether any of the organelles are agents, each “saying alive” in its own way.

Consider the star-shaped contractile vacuole, portrayed in the figure as a circle with legs extending out into the interior of the cell. I suppose that the legs go far enough to contact cell membrane in the furthest reaches of the cell. When this agent activates, the cell squishes and sloshes, moving the other internal agents around. Maybe, that is the way the paramecium says, “What the hell is that?”

After all, not all paramecium get treated to a dose of nicotinic acid.

0501 Perhaps, the star-shaped contractile vacuole was once an agent. But, now it is a subagent within the agency of the paramecium. Indeed, it is a reactionary subagent.

0502 Section 10.1 wraps up with multicellular holobionts, insect colony holobionts, and human institutional holobionts. The pattern repeats on larger scales. On every scale, an agent3 flourishes on its own unique final causality1.

0503 For example, when I go to work at the big, bureaucratic, institution that employs me, I imagine that one of my duties is to operate as a reactionary subagent, like the contractile vacuole.

So, I notice things going on (SVs) and then think of comments to agitate my colleagues (SOe).

Sometimes, my colleagues think that I act like a micronucleus or an anal pore, but the contractile vacuole is the best analogy. As experts in paramecium biology say, “The contractile vacuole stirs the pot.”

0504 This brings me to section 10.2, concerning interactions among subagents.

The self-governance3b that arises from possible courses of action1b may be modeled on the basis of interactions among subagents. The interactions may be direct (for example, the spindly legs of the contractile vacuole pulling at various membranes) or indirect (for example, the macronucleus secreting a hormone that calms the contractile vacuole down, while inducing the anal pore to release its contents).

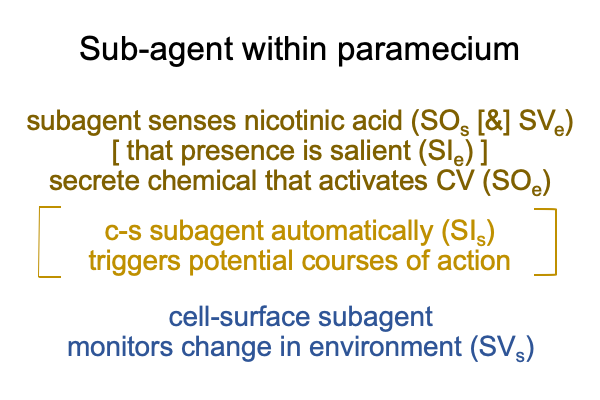

0505 Here is a picture of how the contractile vacuole (CV) gets going in the first place (at least, during the current experiment that I am conducting). “C.s.” stands for “cell surface”.

0506 Now, I translate this example of semiotic agency into me, as a contractile-vacuole-like subagent with the paramecium that is my large bureaucratic organization.

At work, my subagent-area does not really physically work. It mentally works, if I can call it that.

There are many different people in my sector of cubicles. One loves cabbage. I don’t know why.

One of the byproducts of cabbage digestion is the flatulatory release of methane with a slightly sulfurous odor.

0507 When one of my colleagues (the cell-surface subagent) notices the scent, she writes a little note and leaves it on my desk. The note says, “Cabbage”. Don’t say it with an English accent, as if it is a vegetable. Say it with a French accent, as if it is like a drop of nicotinic acid falling into a petri dish.

At this juncture, I (the contractile vacuole) saunter from my desk to the water cooler and say, with a tone of resignation, to whoever is present, “My it smells like someone ate too much cabbage yesterday.”

0508 The author notes that the aim of the subagent is not merely an isolated task. Rather, the goal links back to the goals of the entire organism (the holobiont).

0509 If asked why I stir the pot, my answer would be… um… that my activities further the interests of my corporation by taking the attentions of my fellow workers away from the misery of serving as cogs in a soulless machine and towards making fun of and gossiping about one another. It’s not enough to be “productive”. We ought to enjoy working together as a “team”.

In short, my activities, like those of the contractile vacuole of the paramecium, are osmotic in nature.

0510 Of course, my boss, a figurative macronucleus, has different ideas about the matter.

0511 The author has a label for the multiplicity of final causations among subagents. The term is “heterarchy”. In heterarchy, the semiotic agencies of subagents can be ranked by the degree in which they match (or support) the goals of the organism.

Of course, any ranking is highly contingent. I mean, for the paramecium, what happens when the anal pore goes on strike? Surely, its mission goes to number one. Or is it two?

0512 The author offers a list of the benefits of modularity (or subagents) besides being productive and having fun. This list includes efficiency, reusability, robustness and adaptability. The list applies to the holobiont. The list also applies to the contiguities within the

S&T noumenal overlay.

Each experiment that I perform on my petri-dish paramecium adds further details.

0513 Suppose, instead of pure nicotinic acid, I release one drop of a very concentrated solution of potassium chloride. The paramecium’s environment has too much salt. Water seeps out of the paramecium. (The opposite happens when the environment has too little salt. Then, water seeps into the paramecium. But, I do not have a dropper bottle labeled, “Depletion of Potassium Chloride”. So, I cannot conduct the experiment.)

0514 Either way, the contractile vacuole serves to keep the cell from shrinking or expanding due to osmotic disequilibrium. The contractile vacuole can also stir the pot, just like I do at the water fountain.