0561 What about learning, the topic of section 4.6?

A renown form of learning is the conditioned “reflex”. It is not really a reflex. But, the conditioning make it look like one. Another label is “stimulus-response”.

0562 Figure 4.7 in the text has a picture of Pavlov’s famous experiment. A dog is positioned within an sling in order to measure the amount of drool that it slobbers while waiting for dinner.

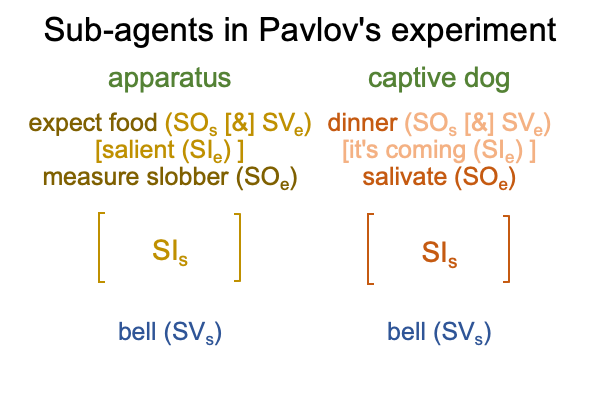

If the experimental apparatus and the captive dog are subagents of an empirio-schematic inquirer, the subagents are working in parallel, not in sequence.

Here is a picture.

0563 Is that correct?

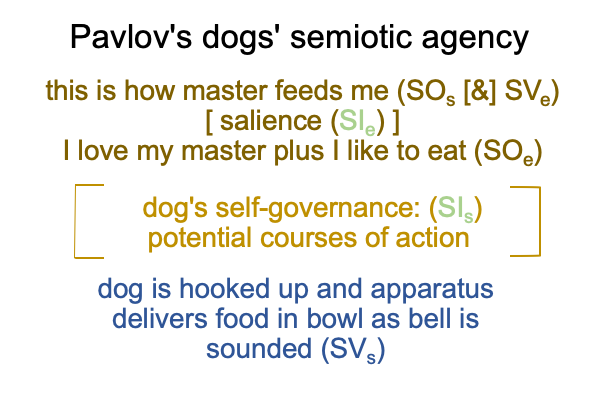

The dog is not really captive. Instead, the dog is so tame as to allow the pelvis to be put into a sling and the mouth attached to tubes that suck up saliva. The bell2a (SVs) stands for dinner2b (SOs) according to the self-governance3b of its neural system operating on possible courses of action1b (SIs).

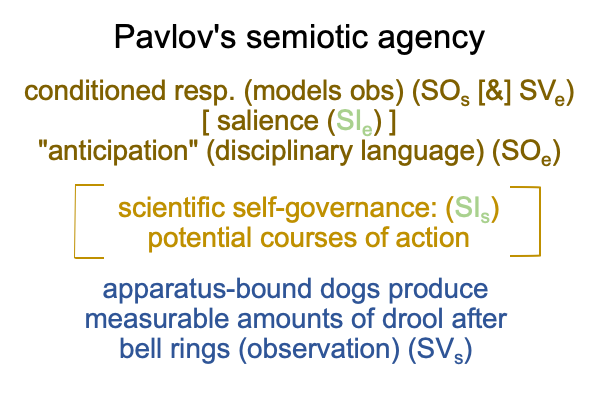

According to the scientist, who is so clever as to devise a way to measure the volume that a dog drools using tubes to suck the drool as it spills between mouth and lips, the bell2a (SVs) stands for the expectation of food2b (SOs) in regards to scientific inquiry3b into the potential of ‘a rigorous conceptualization of anticipation’1b.

0564 Does Pavlov induce the dog to drool in anticipation?

Does the dog’s saliva fulfill Pavlov’s expectations?

What is it about dogs that allows them to go along with such foolishness?

0565 I think that dogs are adapted to believe that humans are their pack leaders. There is a motive for this belief. Humans are not as cruel as wolves. An alpha wolf is downright mean and expects to be… um… top dog all the time. A human pack-leader is wonderful in comparison. Not only do humans not bite back, although they occasionally hit and are nasty, they tend to share their food as if the dog is part of their pack… er… family.

It’s a nice gig, if you can get it.

0566 So, by instinct, the dogs know that Pavlov is pack leader. Pack leaders have expectations. So, the dogs go along with what Pavlov wants because, well, they want to please their pack leader.

05670 What do Pavlov’s dogs learn?

First, Pavlov’s dogs learn how to let themselves be hooked up to that stupid sling, which obviates the use of their hind legs. Totally awkward. Then, the dogs learn that the drool measuring apparatus hooked to their heads is not going to hurt them. Dogs that can not handle this lesson are cut from Pavlov’s pack. Finally, the dogs find out what the apparatus is all about. It is the way that master is going to feed me.

0568 So, Pavlov’s dogs learn far more than the business about conditioned response.

Indeed, the salivation is merely an exemplar sign-relation that is built into their subagency. If food is around, prepare to eat.

0569 Meanwhile, Pavlov achieves what he wants to achieve. Anticipation is a model that is associated to conditioned responses. The model soon replaces the noumenon of what those Pavlov-loving dogs endured. Today, the noumenal overlay of “anticipation” is objectified by the phenomena of psychological experiments conducted under the labels of “operant and instrumental conditioning”.

Today’s state educators perform these experiments on young children, completely unaware that the noumenon that the children experience is not quite the same as the model that substitutes for the noumenon.

0569 Does that mean that Pavlov is an subagent for something bigger, such as science as an institution?

I wonder. In the following figure, Pavlov’s semiotic agency touches base with all three elements of the empirio-schematic judgment.

0570 This raises a parallel between Pavlov, the scientist, and his dogs, the subjects of scientific inquiry.