Looking at Michael Tomasello’s Book (2008) “Origins of Human Communication” (Part 2 of 12)

0096 Now, I attend to the book before me. Right away, I suggest that the reader look at chapter seven. Tomasello is very organized. The final chapter provides an awesome summary of the entire book.

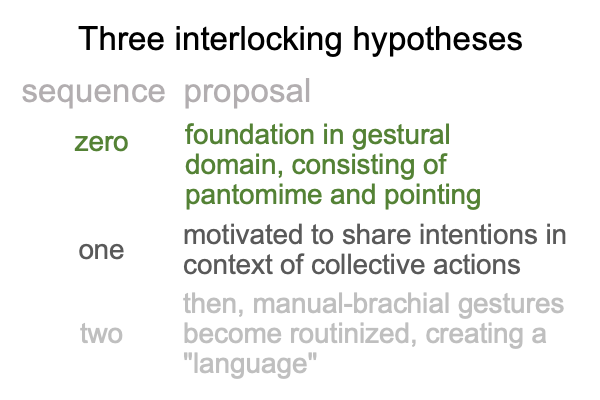

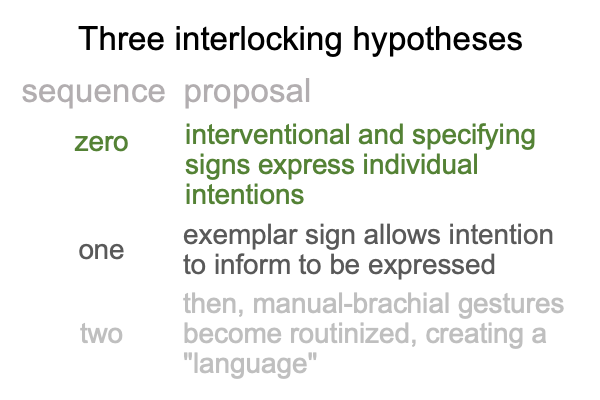

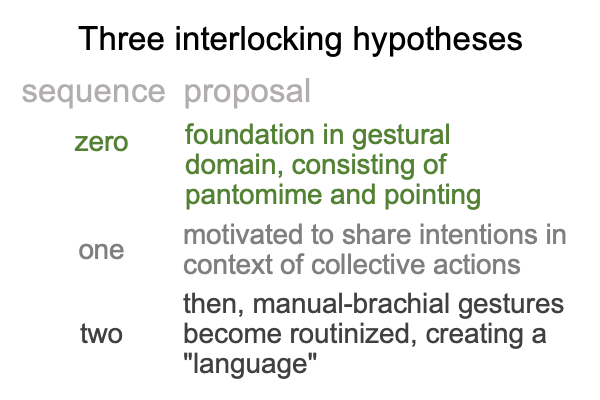

0097 In chapter one, the author proposes three interlocking hypotheses about the origins of human communication.

First, human cooperative manual-brachial gestures evolve initially in the domain of pantomime and pointing.

Second, this evolution is potentiated by skills and motivations devoted to sharing intentions in the context of collaborative activities.

Third, once the second point is in place, linguistic conventions evolve.

0098 Here is a list.

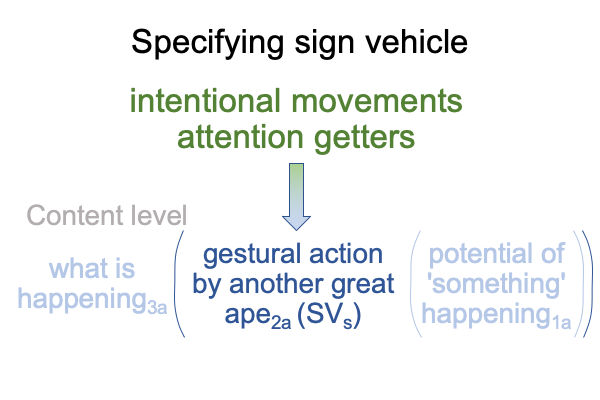

0099 To start, Tomasello notes that all four species of great apes, who are presumably closer in character to our last common ancestor than we are, learn and use manual gestures in flexible ways. In contrast, vocalizations are unlearned and inflexible. These observations support the first hypothesis.

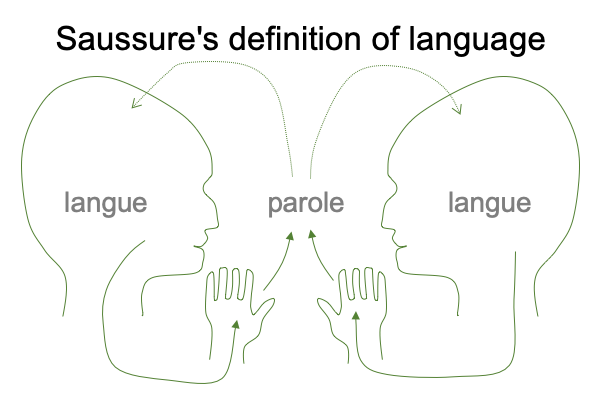

Next, Tomasello argues that the path from (situation-revealing) ape vocalizations to (content-revealing) human speech-alone talk is untenable. The hominin capacity for language starts with manual-brachial gestures and ends with speech-alone talking civilizations.

0100 So, there must be a twist in human evolution.

Notably, these are also key claims in Razie Mah’s three masterworks, The Human Niche, An Archaeology of the Fall and How To Define the Word “Religion” (available at smashwords and other e-book venues).

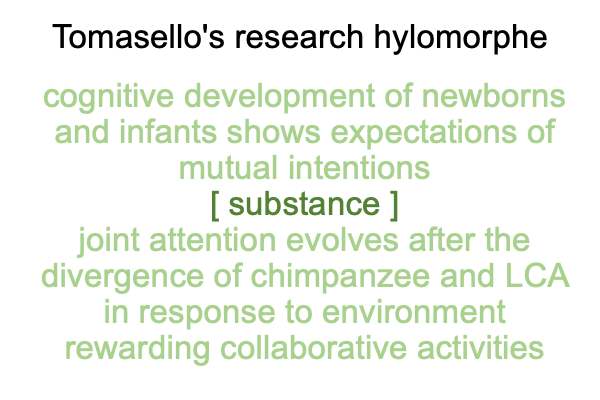

0101 So, what is this business about “shared intentions”?

How do manual-brachial gestures accomplish that?

Consider the dog. Dogs adapt into the niche of humans sharing intentions. They read human body language. In a simple experiment, I stand on the other side of a low table with two overturned bowls. If I look at one one bowl, the dog will sense that this is the bowl that hides the treat. My dog and I share a common conceptual ground. She knows that I give information to her for her benefit, rather than my own. She would be very upset if I gazed at the wrong bowl, and, when she overturned it and found nothing, saw me reaching under the ungazed bowl and stealing her treat.

Is sharing food the foundation for shared intentionality?

In captivity, one ape may assist a second ape in getting food, even when that food will not be available to the first ape. That is the type of game that cognitive psychologists design.

0102 But, hominins do not evolve in captivity.

In the wild, shared intentionality proves very helpful.

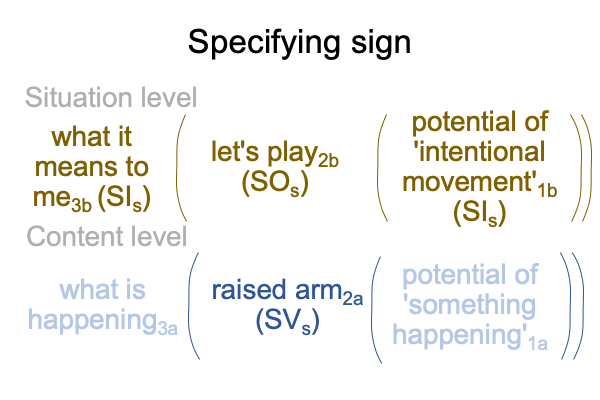

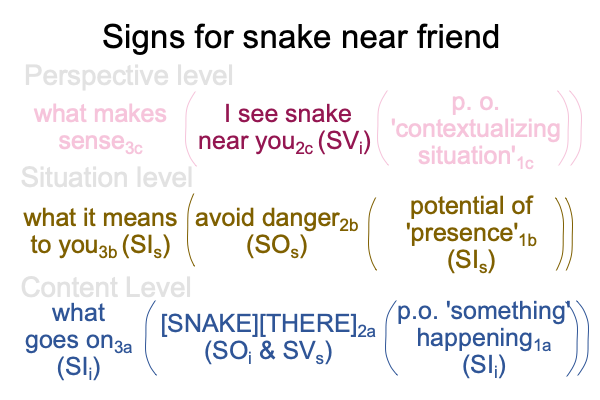

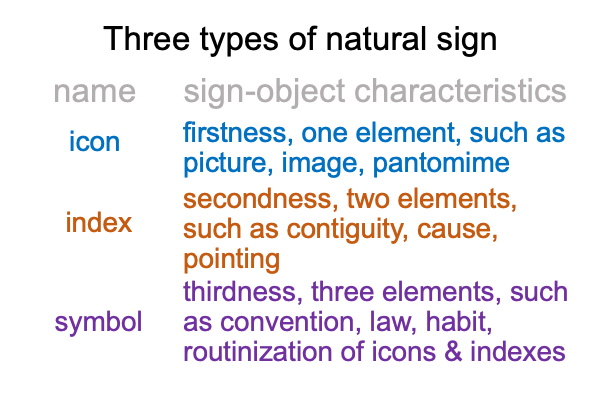

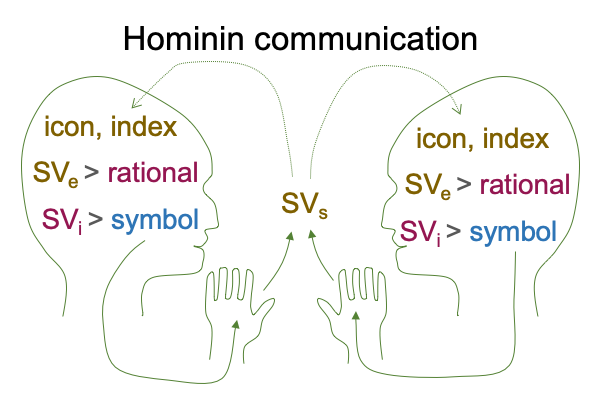

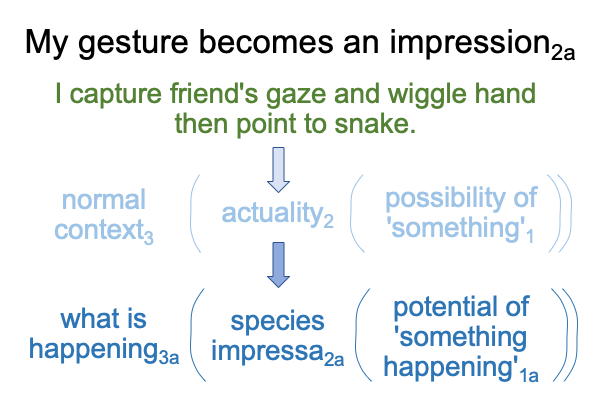

Imagine that I notice that my compatriot does not see a snake nearby in the grass. If I could gesture a motion that looks like the motion of a snake then point to it, that would be far better than sharing food. In hand talk, I could say, “[WIGGLE HAND] [POINT to snake].” Over time, the manual-brachial pantomime becomes routinized as the hand-talk word, [SNAKE].

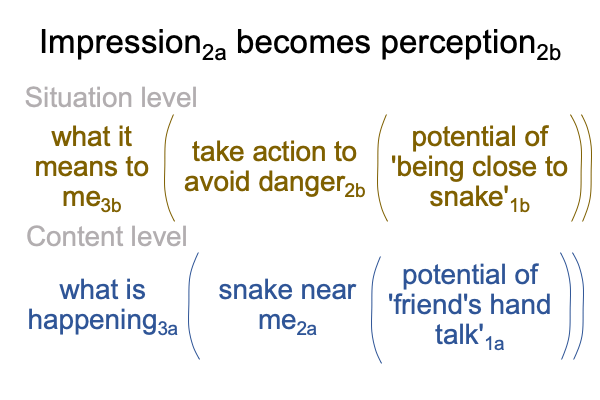

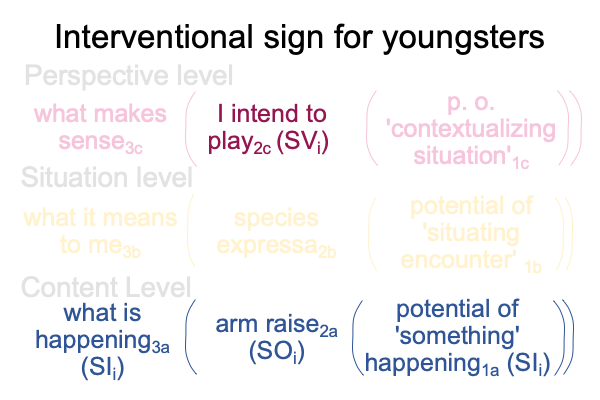

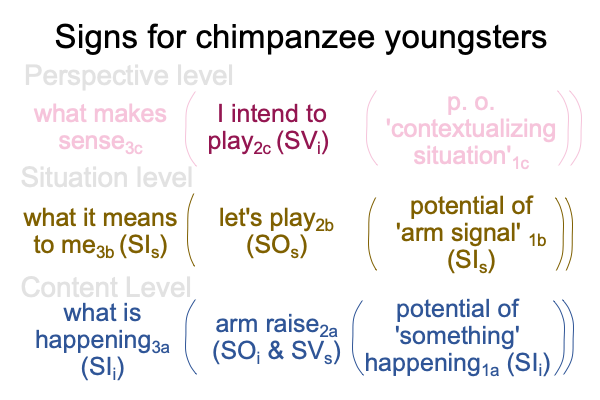

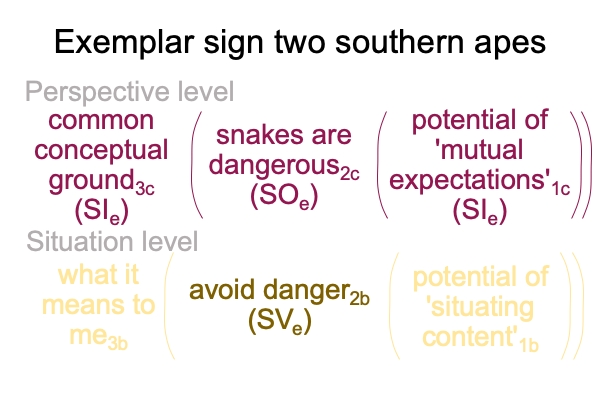

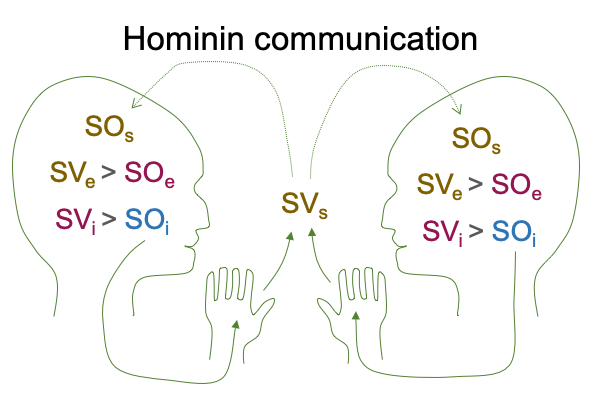

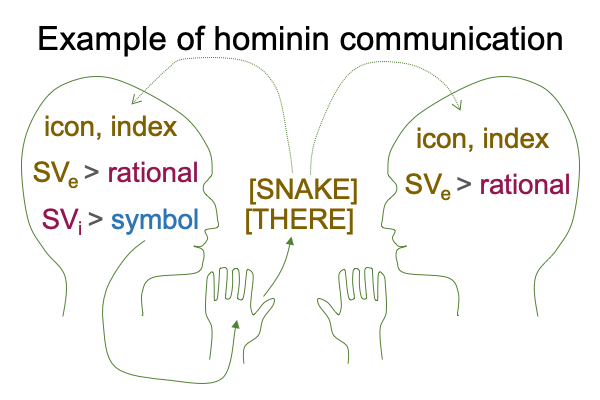

0103 Here is a picture.

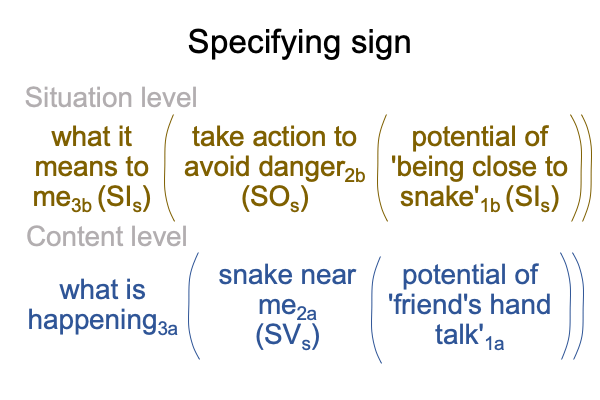

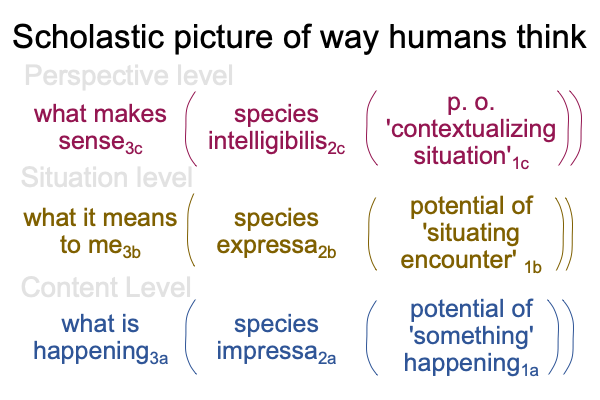

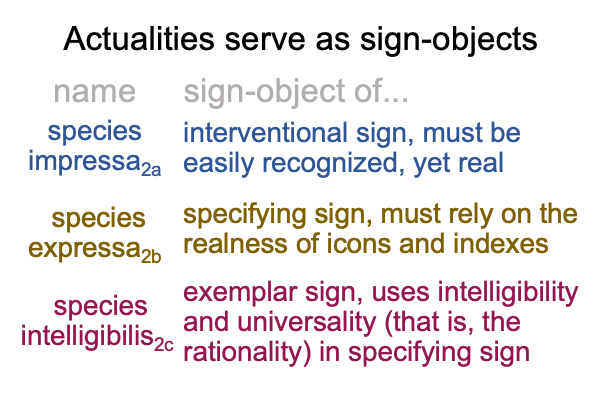

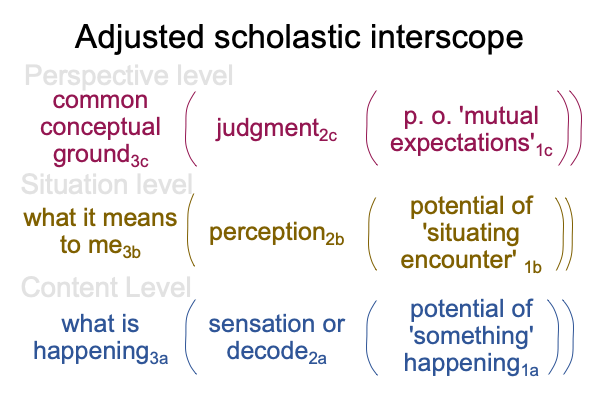

0104 In order for my gestural action to become a content-level actuality2a, the other hominin must presume that his impression of this actuality2a occurs in the normal context of what is happening3a and holds the potential of ‘something’ happening’1a.

My domesticated dog knows this.

But, what of my compatriot from 3Myr (millions of years ago)?

0105 Ah, that is why Tomasello’s label of “shared intentionality” is so evocative.

The “shared” goes with the normal context of what is happening3a.

The “intentionality” goes with the potential of ‘something happening’1a.

0106 My gestural action changes my friend’s impressions.

If I do not share, then I intend for my friend to get a snakebite.

In Christian parlance, this is called “a sin of omission”.

In the parlance of natural history, this is called “natural selection”.

The problem is that part of me dies when my friend succumbs to the toxic injection.