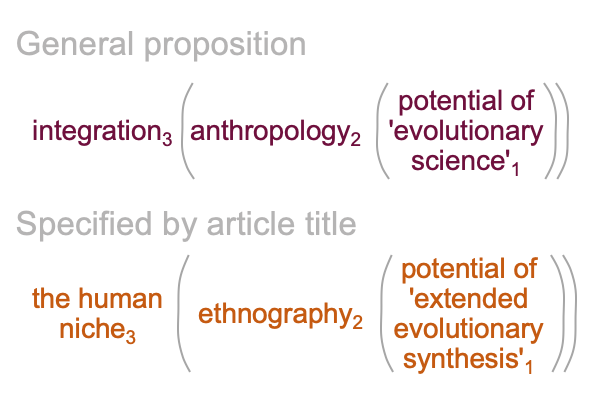

Looking at Augustin Fuentes’s Article (2016) “The Extended Evolutionary Synthesis…” (Part 13 of 16)

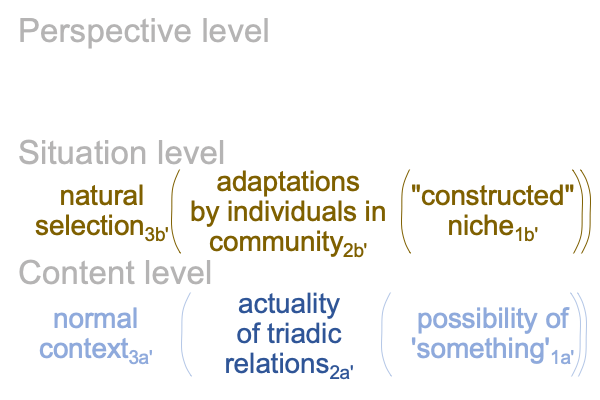

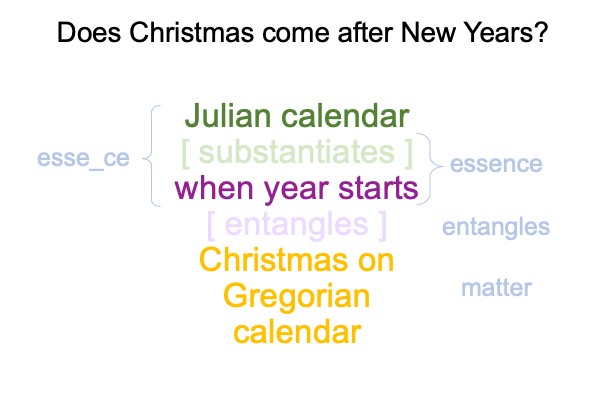

0136 The question that I failed to address is this, “Does the author’s figure 2 comport with the two-level interscope for natural selection?”

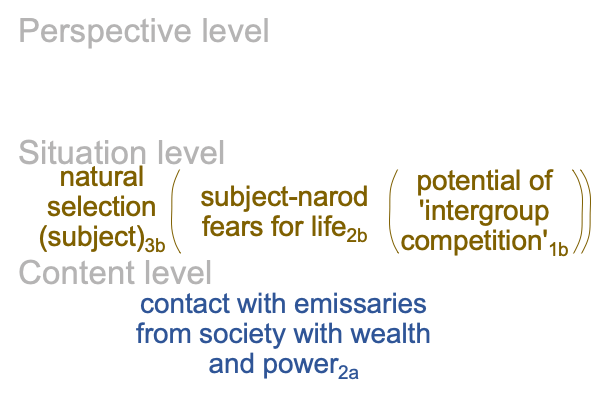

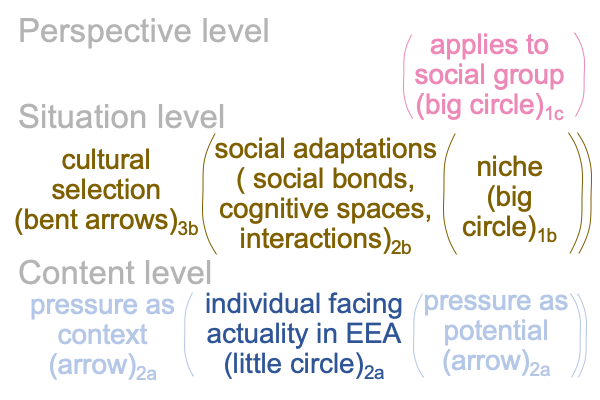

0137 What if I replace “natural selection” with “cultural selection”?

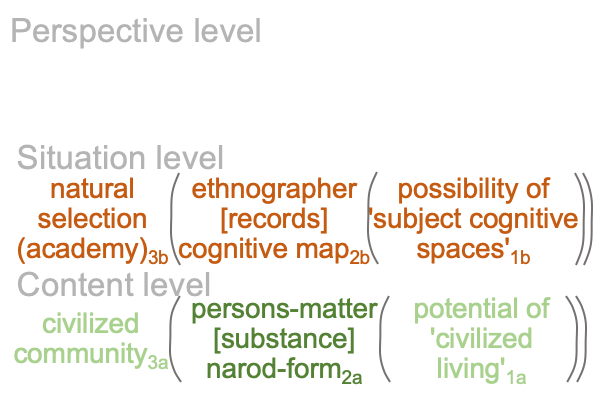

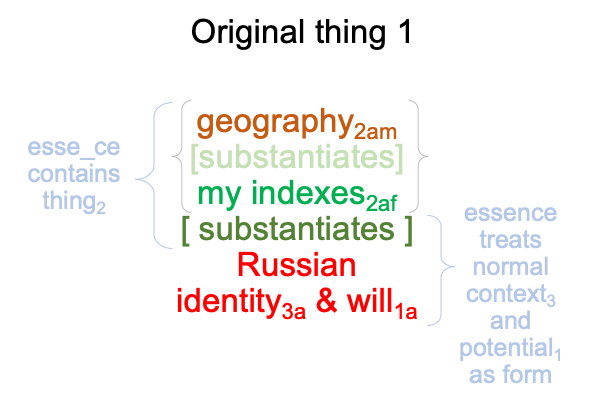

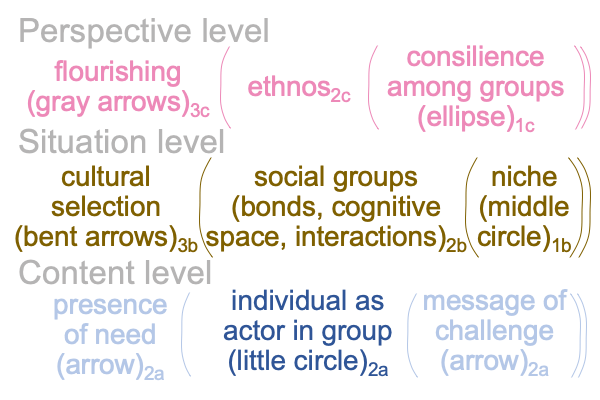

Here is a picture.

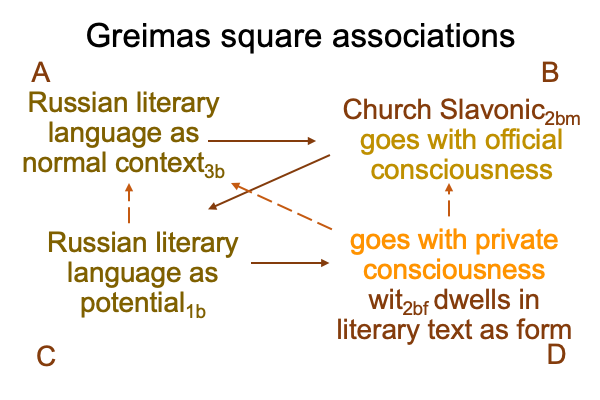

0138 The normal context of cultural selection3b brings the actuality of social adaptations (including social bonds, cognitive spaces and cooperative interactions)2b into relation with a social niche1b, defined as the potential1b of individuals facing natural selection pressures in the environment of evolutionary adaptation (EEA)2a.

0139 Of course, these social adaptations2b potentiate the social group1c, which, as noted earlier, includes the social circle that is under the most significant selective pressure.

At the same time, I may say that the potential of the social group1c creates the situation where social beings2b are adaptive.

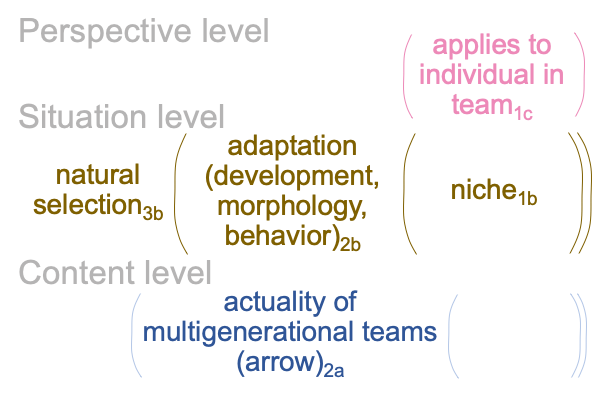

0140 Next, imagine that the salient social circle is the team (15). Over generations, the team1c encourages social adaptations2b that rewards individuals with phenotypes that are appropriate to that team2a. In other words, successful teams2a, as the medium responding to evolutionary pressures associated with obligating collaborative foraging,produces a selection pressure3b on the individual2b.

One of the social adaptations2b is protolinguistic hand-talk2b. The semiotics of protolinguistic hand-talk2a become the actuality independent of adapting individuals (species)2a. Individual adaptations2b encourage sensible constructionduring team activities. Hand-talk facilitates sensible construction.

0141 Next, imagine that, during the domestication of fire, cooking changes everything. Cooking with fire unlocks hitherto sequestered nutrients. More teams can be successful. More teams means larger brains and larger groups. Bands (50) grow into communities (150). Communities are teams of teams.

Enough versatility exists among teams that ecological pressures are mediated by organizational capacity.

In short, the salient social circle is now the community (150).

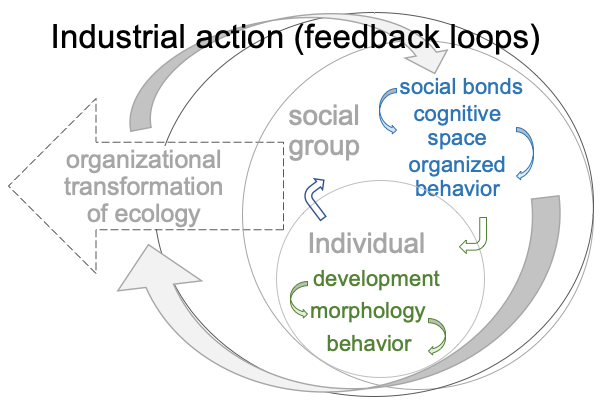

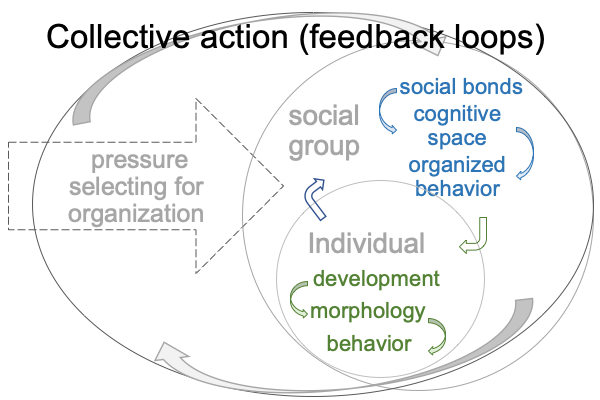

0142 The author’s next set of feedback loops is collective action, which roughly corresponds to the interactions within a community and its environment.

0143 This set of feedback loops demands that a perspective level comes into play. The situation-level might be family (5), friends (5), team (50) and band (50), as well as mega-band (500) and tribe (1500). A perspective-level adapts to the community (150).

After all, that is what Robin Dunbar’s correlation between human brain size and group size predicts. Human brains are adaptive for groups with a size of 150. But, a community contain smaller groups, so one of the jobs of the community is to bring harmony among the teams, friends and families. One of the other jobs is to face outwards towards other communities (that is, mega-bands and tribes).

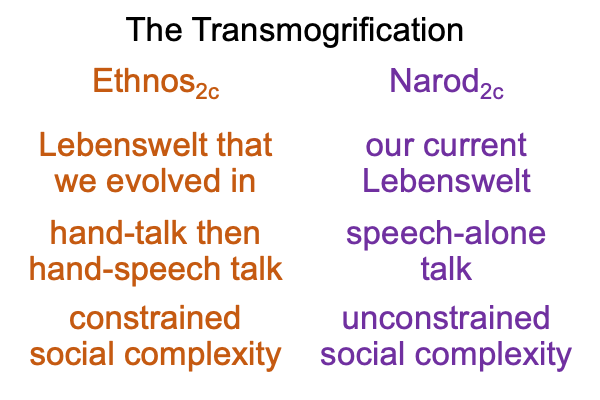

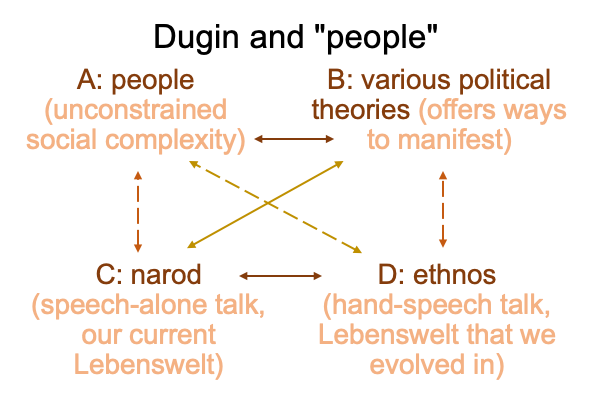

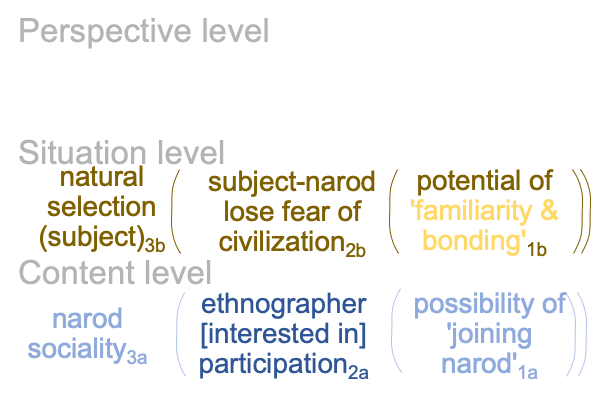

0144 Well, if I add a perspective level to the two-level interscope, then a whole new typology of social bonds, cognitive spaces and cooperative interactions2c manifests. If Dugin is correct, these actualities2c fall under the label, “ethnos”, for the Lebenswelt that we evolved in.

0145 Here is the three-level interscope.

On the perspective level, the normal context of hominin flourishing3c brings the actuality of the ethnos2c into relation with the potential of harmony among all social circles, including those smaller and larger than the community1c.

On the situation level, the normal context of cultural selection3b brings the actuality of social groups2b into relation with the social niche2a, consisting of the potential of individuals in community2a.

On the content level, the presence of need3a brings the individual in community2a into relation with the potential of meeting a challenge1a.

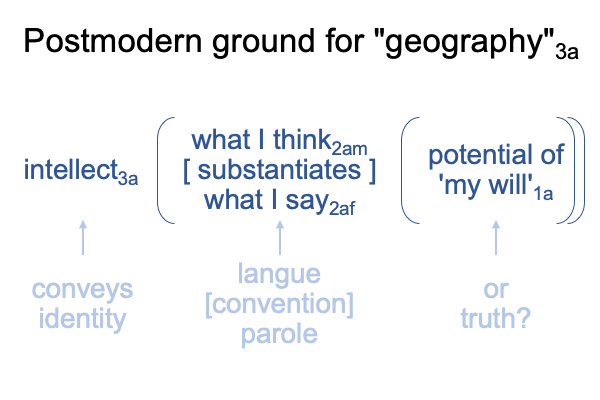

0146 One question is, “Who constructs this content-level normal context3a and potential1a?”

Plus, how are these normal contexts3 and potentials1 constellated in niche construction?