Looking at George Mikhailovsky’s Chapter (2024) “Meanings, Their Hierarchy, and Evolution” (Part 2 of 9)

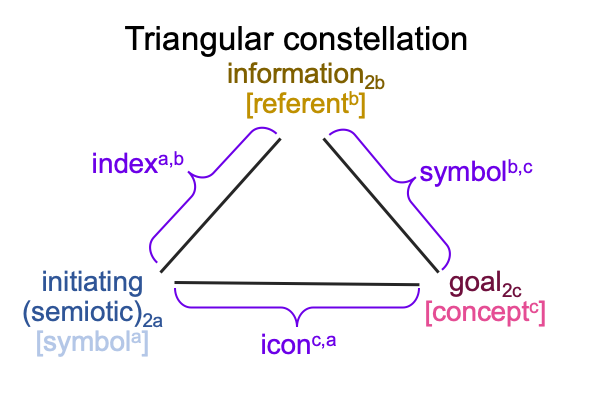

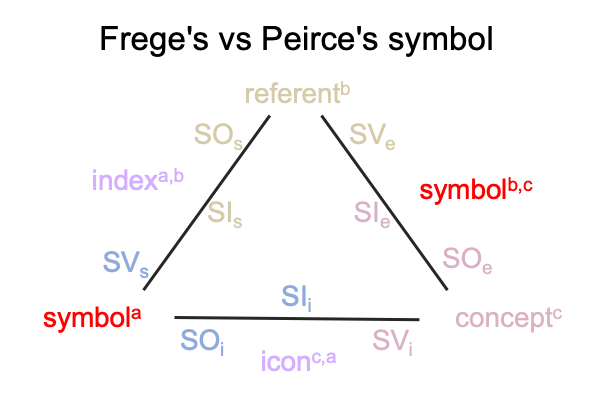

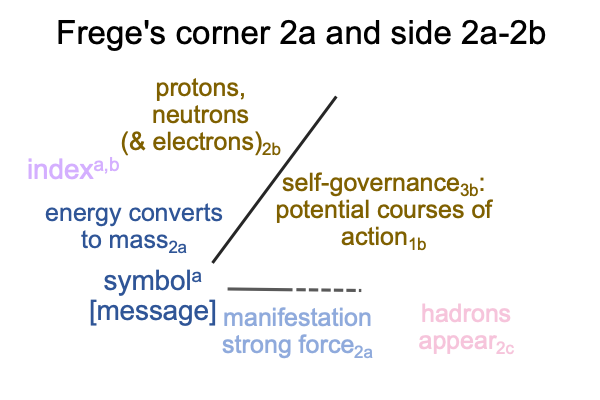

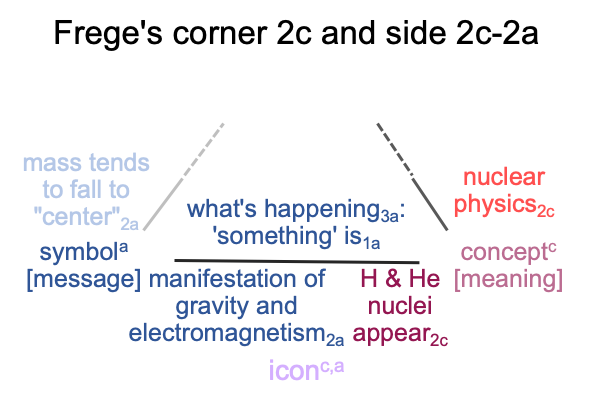

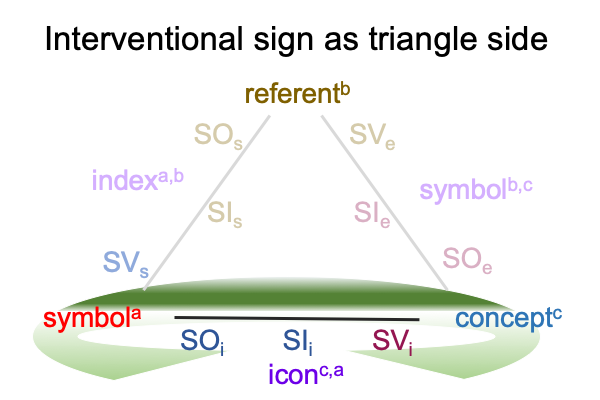

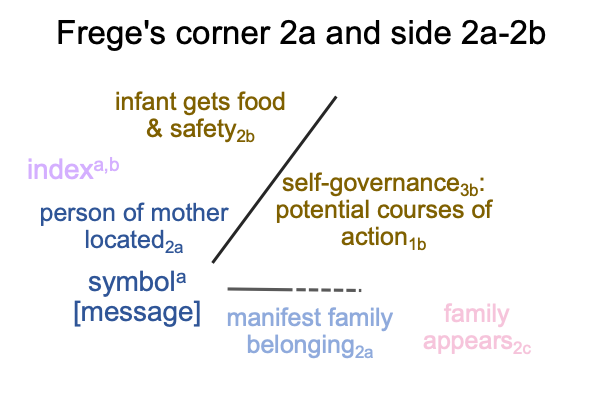

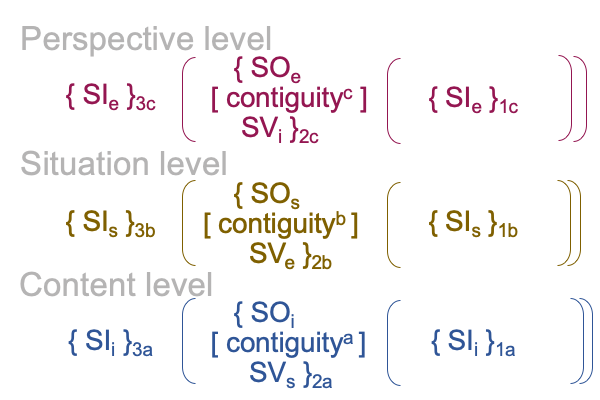

1065 I am compelled to diagram these dyadic actualities, with their contiguities in tow.

Here is a picture that looks like an interscope that I have seen before.

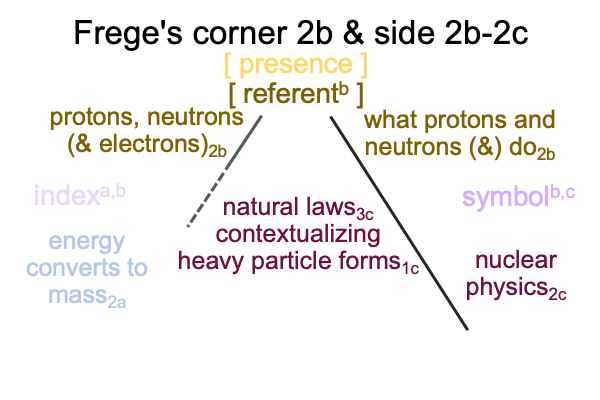

1066 This figure differs from previous interscopes of the specifying, exemplar and interventional sign-relations.

The contiguities no longer correspond to the three potentials1 underlying a spoken word2 in the normal context of defintion3.

The contiguities are labeled with a superscript that indicates the category of that level of the dyadic actuality. The superscripts are “a” for content level, “b” for situation level and “c” for perspective level.

1067 Each dyadic actuality2 is a hylomorphe, similar to Aristotle’s matter [substance] form.

For each actuality2, the sign-object is like matter, the contiguity is similar to [substance] and the sign-vehicle mimics form.

The sign-object confers presence (or esse_ce as matter [substantiating]).

The sign-vehicle for the next sign-relation is like a shape that contains the presence (or essence as [substantiated] form).

1068 The diagram may be confusing.

For each sign-relation, the sign-vehicle and the sign-object are on adjacent levels. In other words, each sign-relation crosses levels.

But, within each level, the dyadic actuality2 consists of a contiguity between a sign-object (for one sign-relation) and a sign-vehicle (for the next sign-relation in the sequence: specifying, exemplar, interventional, specifying, and so on).

1069 Why do I construct this somewhat ambiguous interscope?

The answer will soon be obvious.

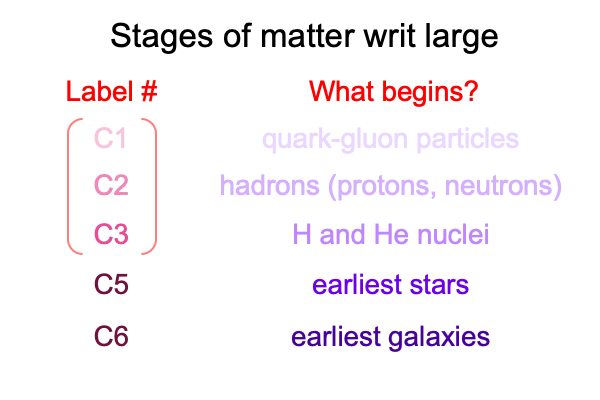

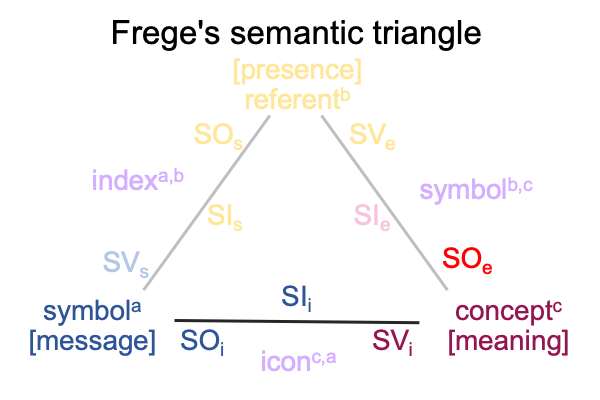

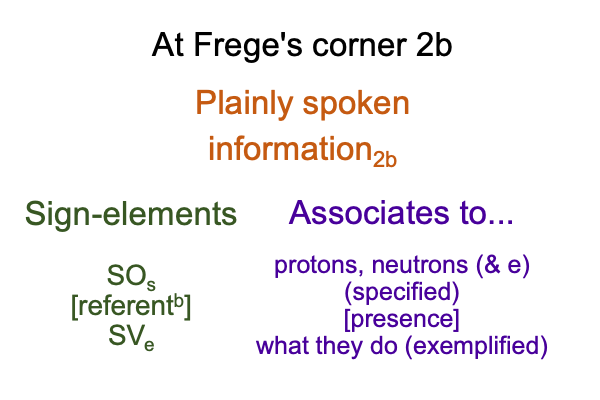

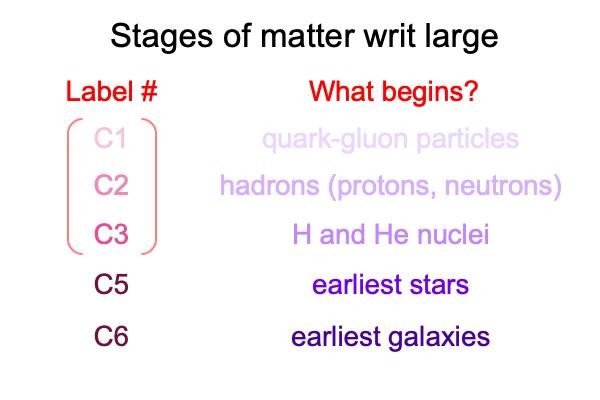

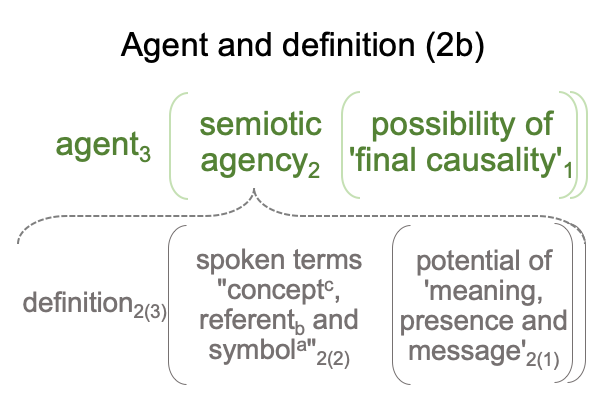

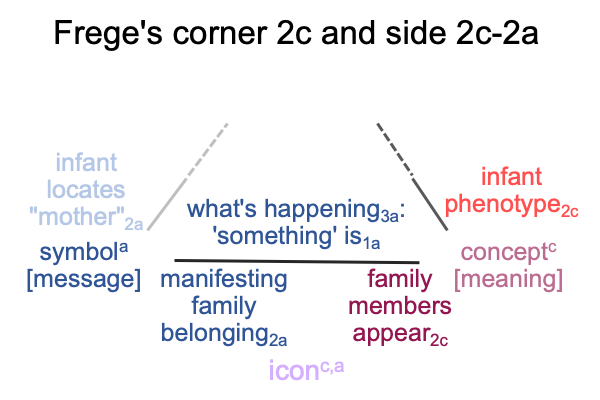

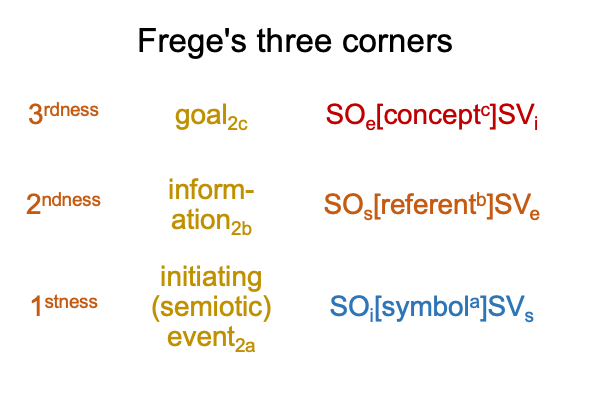

1070 In the introduction (section 6.1), the author opens with three situations where the word, “meaning” is typically used (which corresponds to the three sign-objects in the above interscope). Then, the author says that he will analyze all three types of situations, starting with the third and using Gottlob Frege’s semantic triangle: referent, symbol and concept (or meaning).

To me, this announcement runs counter to a prior announcement, made a few paragraphs prior, that the author intends to focus on the first two situations.

Dear reader, when a sequential contradiction appears in a text, when the author makes one point and then later presents the same point in a completely different manner, take note. Either there is something wrong with the author or the author offers a clue that there is a frame shift in the text. Here, the shift is from common uses of the term, “meaning” to Frege’s referent, symbol and concept.

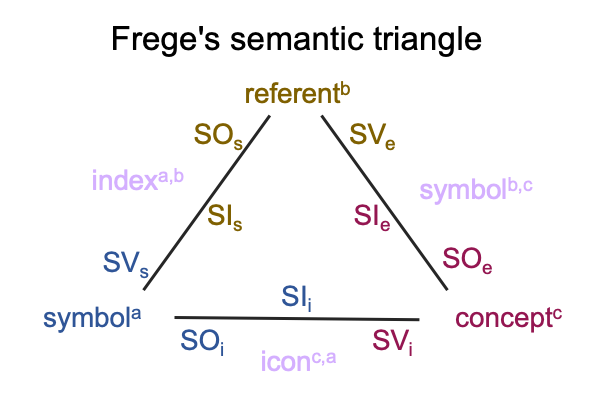

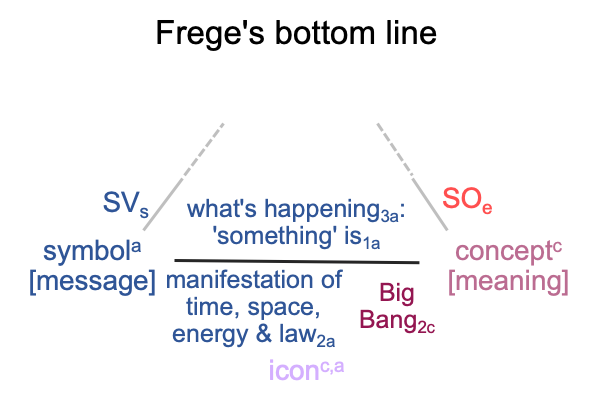

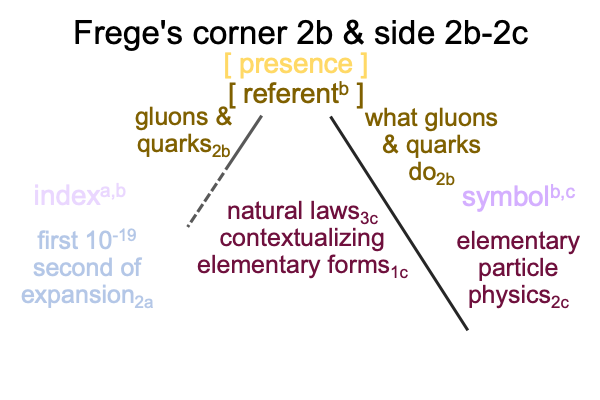

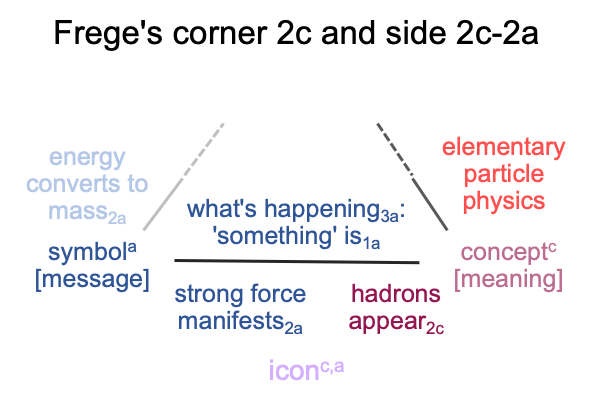

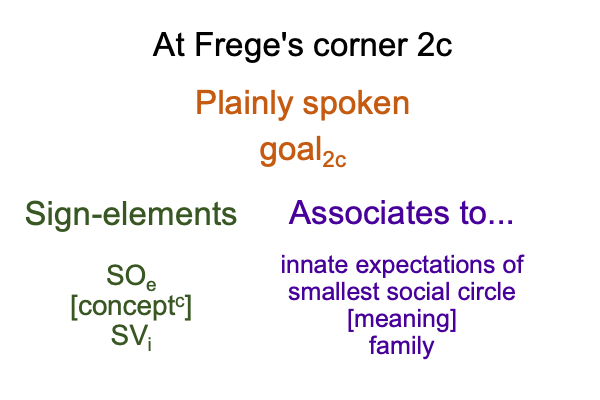

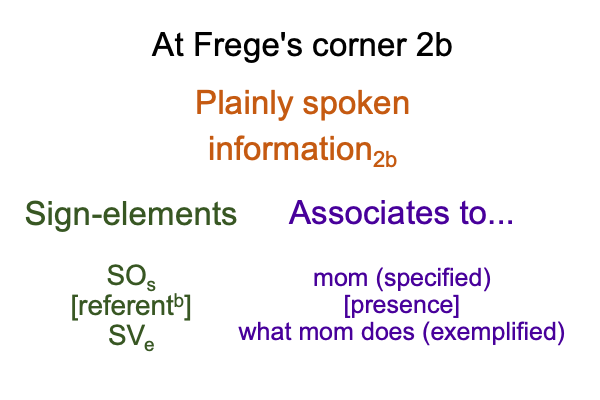

1071 Just as the three common uses correspond with the three sign-objects within the semiotic interscope, Frege’s three terms associate to the three contiguities.

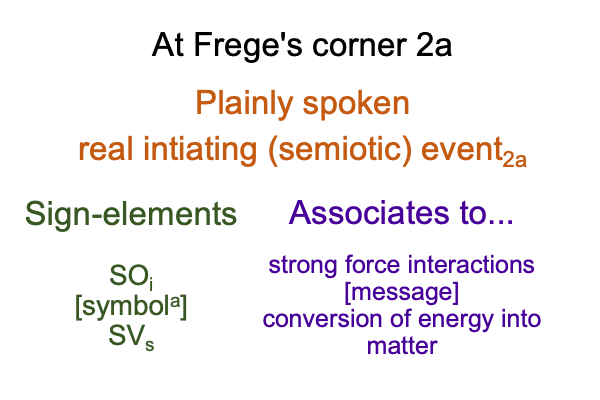

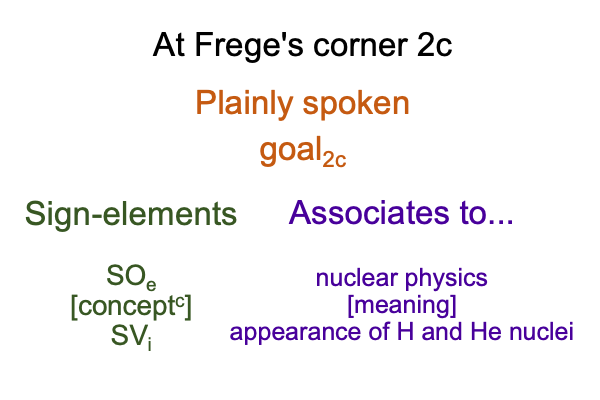

Here is a picture.

1072 What a coincidence!

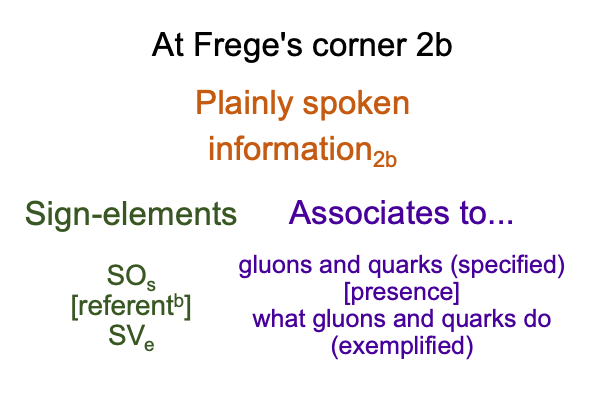

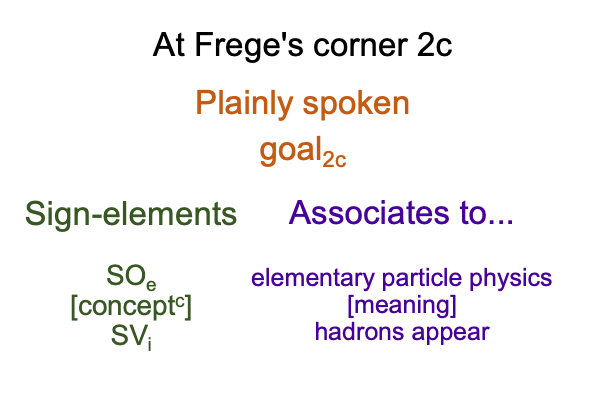

1073 Here, the superscripts and the subscripts provide cues.

The superscripts for the contiguities denote Peirce’s categories of firstness, secondness and thirdness with respect to levels.

The subscripts on the sign-elements denote the type of sign-relation.

The subscripts for the actualities denote level (a, b, c) and location in a category-based nested form (1,2,3).

1074 What about the sign-relation?

The sign-relation does not appear in the figure above.

A sign-relation crosses levels, so it would have two superscripts, one for the SV and one for the SO and SI.

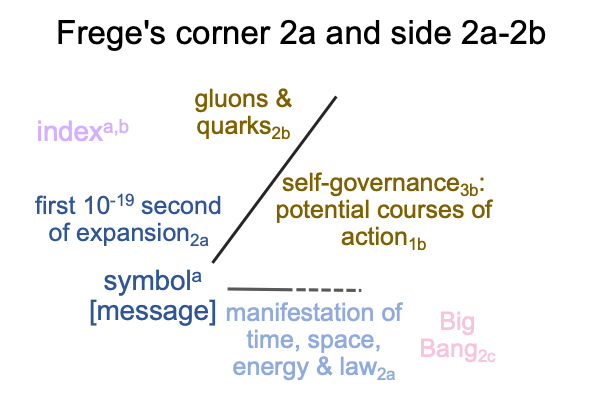

1075 Can I say that again?

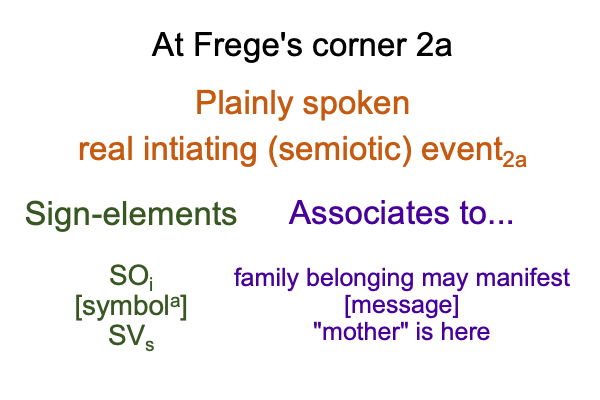

The specifying sign-relationa,b is an indexa,b, because its sign-object, {SOs}2b or information2b, is based on the qualities of pointing, contact, contiguity, cause and effect, and so on.

The exemplar sign-relationb,c may be labeled as a symbolb,c, because its sign-object, {SOe}2c or goal2c, is based on the qualities of habit, convention, law, tradition and so forth.

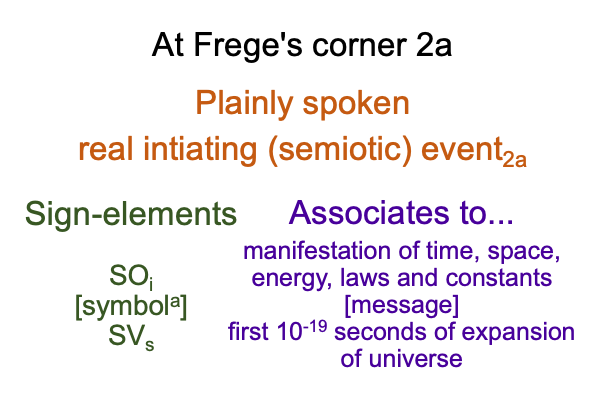

1076 The interventional sign-relationc,a can be labeled as an iconc,a, because its sign-object, {SOi}2a or real initiating (semiotic) event2a, is based on the qualities of images, pictures, similarity, and so on.

Indeed, all five senses offer iconic qualities. Images are not only visual.

I am sure that Daisy and her duck have told me that, through various real initiating (semiotic) events2a.