Looking at Hongbing Yu’s Chapter (2024) “…Danger Modeling…” (Part 6 of 7)

0805 Section 17.4 concerns danger modeling.

The author quotes a great reference. According to Danesi, existential danger is (more or less) “any initiating real event that imperils the existence of things, if allowed to continue without refrain”. For a biological living being, the “thing” is “me”.

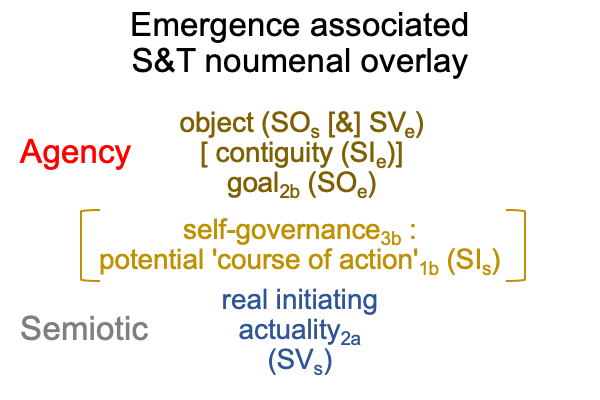

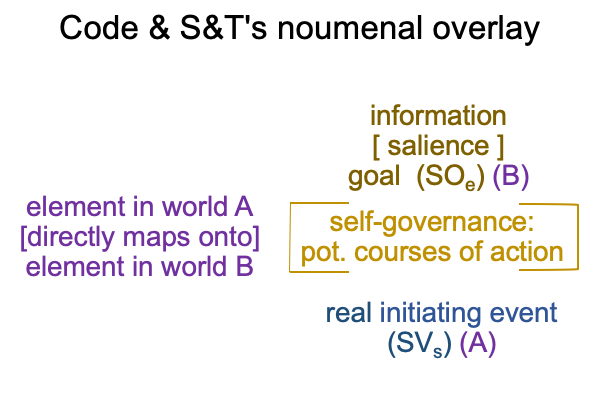

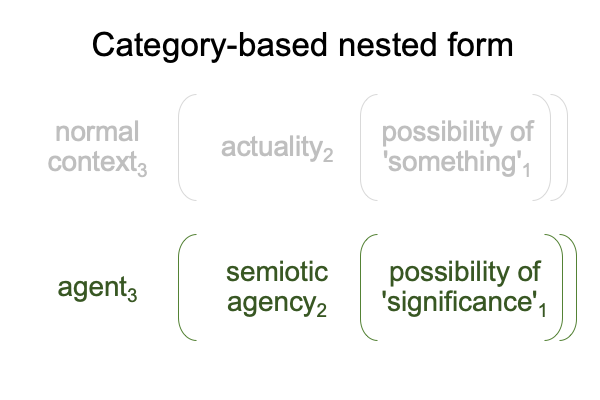

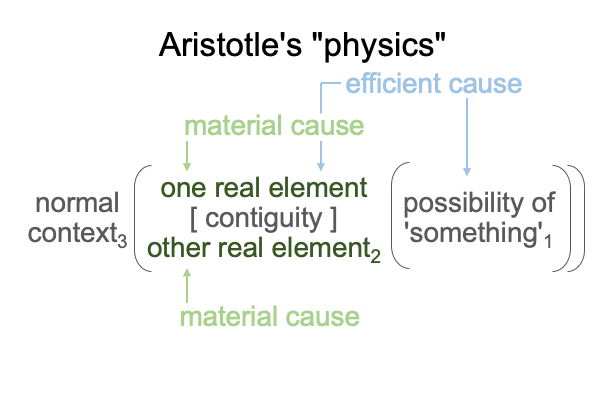

For this examiner, danger starts with a real initiating (semiotic) event (SVs).

0806 When Daisy and I, the leashed dog and her apparent pack-leader, round a corner on our morning walk, we come upon an unfamiliar dog, head buried in a pile of brown leaves. Immediately, Daisy barks. So much for stealth.

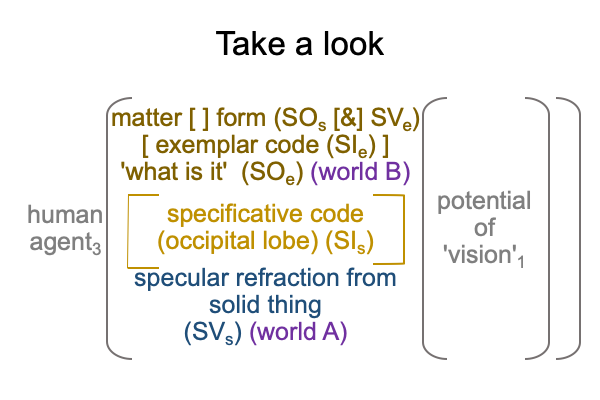

The unfamiliar dog stands erect, with the body of a big duck, a whirl of black and white feathers, in its mouth. I quickly gather information2b. The dog is not much larger and more long-snouted than Daisy. Is the dog growling? It is hard to hear because Daisy is barking as she drags me forward.

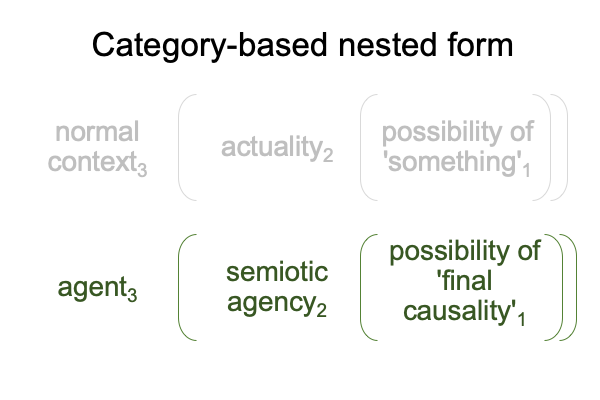

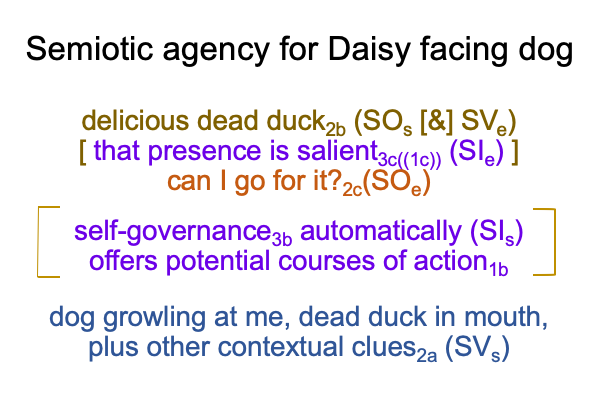

0807 Here is Daisy’s exercise in semiotic agency, at this moment, as far as I can figure.

0808 The beautiful fat ornamental duck, a loner among the geese and the woodland ducks familiar to the neighborhood, was doomed from the start. It lived two years without any other waterfowl of its breed. Now, I suppose, the poor thing met its end by nesting in a pile of leaves where a car decided to park. I wonder whether the driver heard its cries of distress?

Well, at this time of the morning, the car is gone and this dog from some other neighborhood has found a treat to scavenge. Daisy wants a bite of the treat. But, I am not sure that she appreciates what satisfaction of that desire entails.

I do.

0809 I yank Daisy’s chain so hard that she yelps. Then, I drag her in the opposite direction, from whence we came.

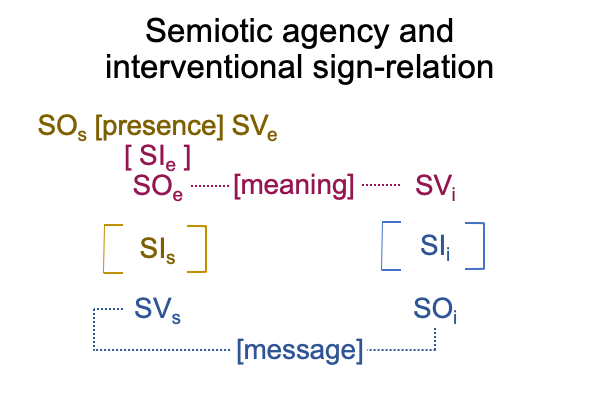

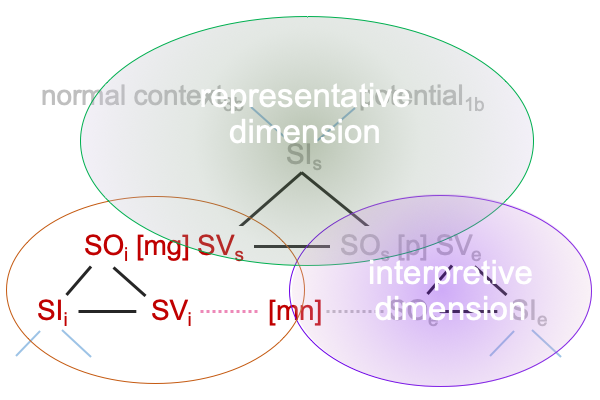

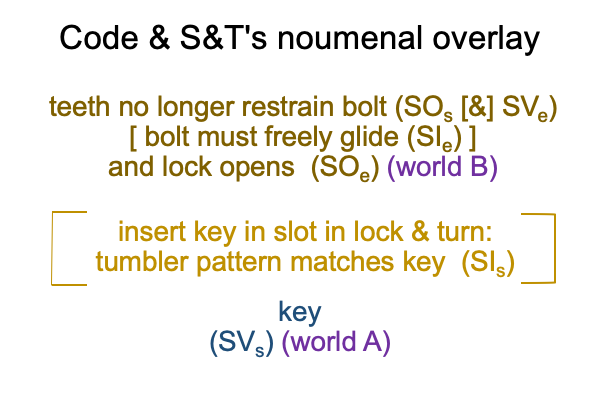

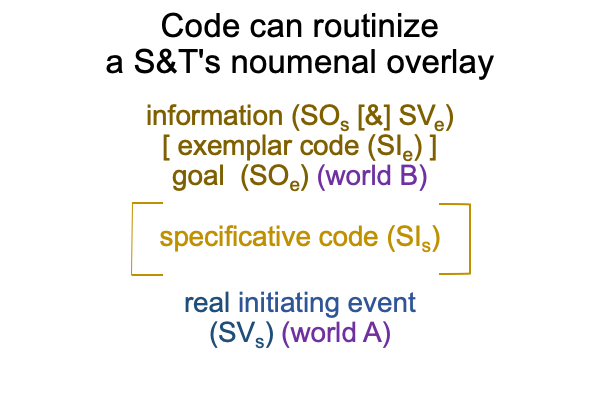

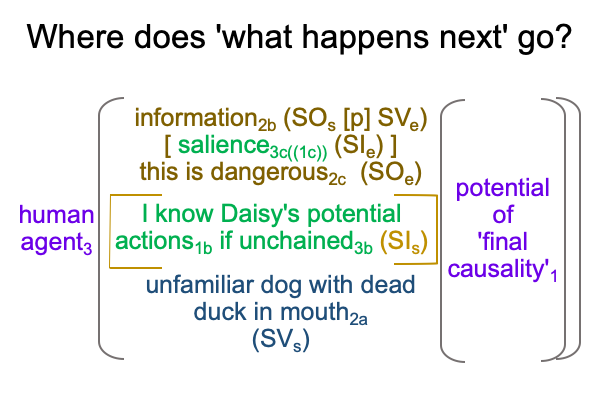

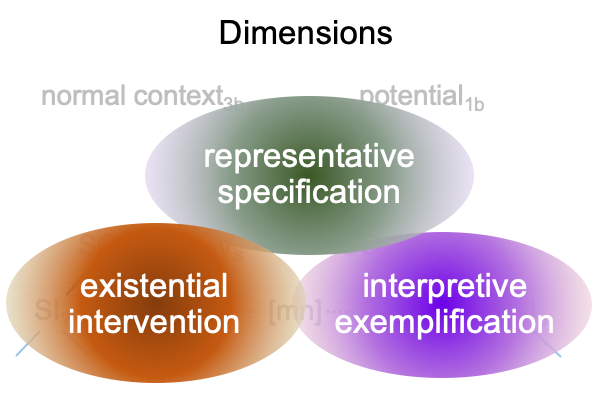

0810 In doing so, I exercise my semiotic agency. In the dimension of representation, I specify information2b about what this means to me and Daisy. I do this through the specifying sign. In the dimension of interpretation, I exemplify what a human pack-leader might do in the face of this type of danger. I do this through the exemplar sign-relation.

0811 At the same time, I face an existential interventional sign-relation. A real initiating event imperils the existence of Daisy, and perhaps me, if Daisy continues without restrain.

0812 As we retrace our steps, I wonder, “Why is that unfamiliar dog snarfing a recently deceased ornamental duck there in the first place?”

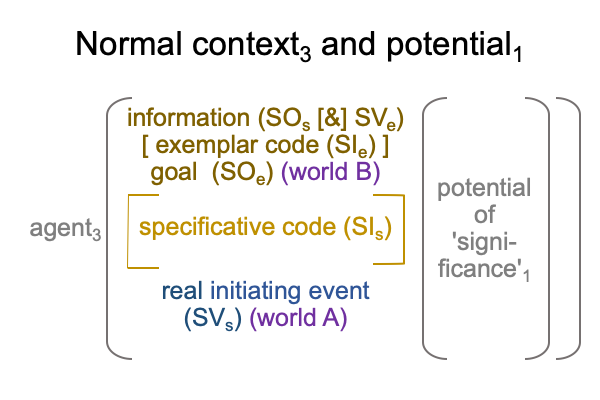

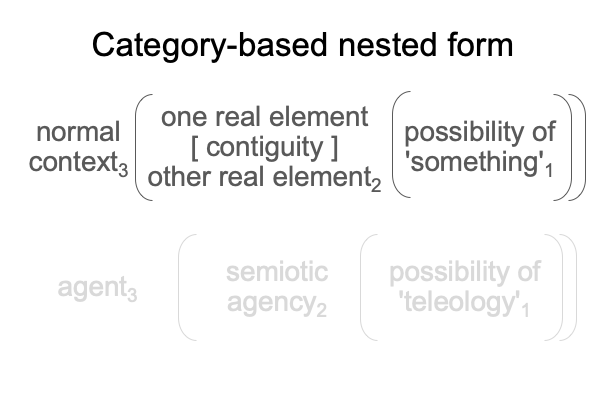

I suspect that the unfamiliar dog wonders the same after our rude interruption of its joy of discovery, so worthy of protection, since the corpse is already in mouth.

0813 To me, the unfamiliar dog intervenes in our morning walk. To that stranger’s dog, Daisy and I intervene in his unanticipated discovery.

To me, the exemplar sign-object (SOe) is “take Daisy on her morning walk”. To the roving dog, the SOe is “chomp down on something both dead and delicious”.

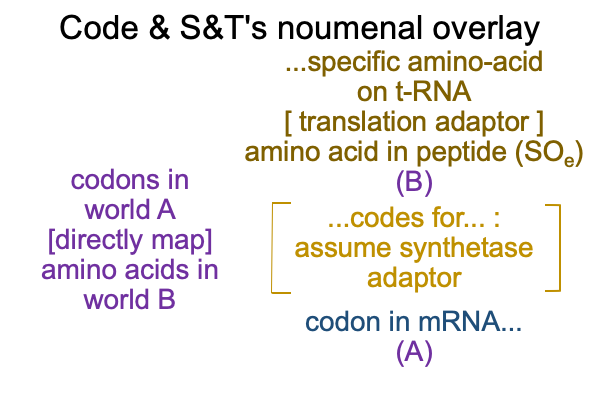

0814 Then, a real initiating (semiotic) event (SVs) occurs. Information (SOs) is specified, within the dimension of representation, then spun into an exemplar sign-object (SOe) in the dimension of interpretation.

To me, the exemplar sign-object (SOe) is “Daisy and I are in danger”. To the roving dog, the SOe is “this competitor is not going to take this treat our of my mouth without a fight”.

That is precisely where our semiotic agencies terminate.

“Terminus” is such a great word. It comes from Latin and means, “an end-point”.

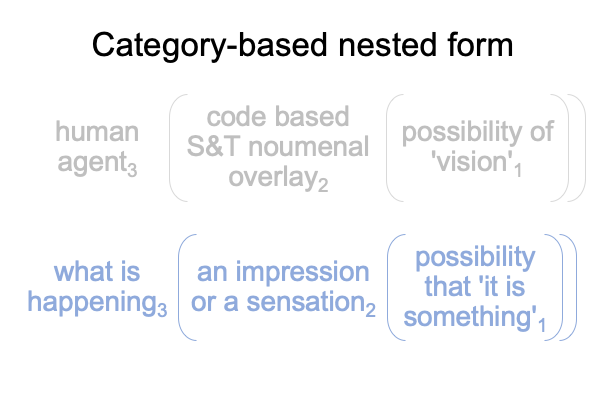

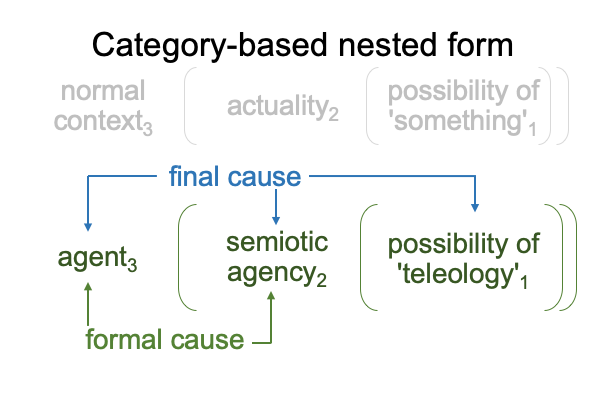

0816 Here is a picture of the three termini and their dimensions.

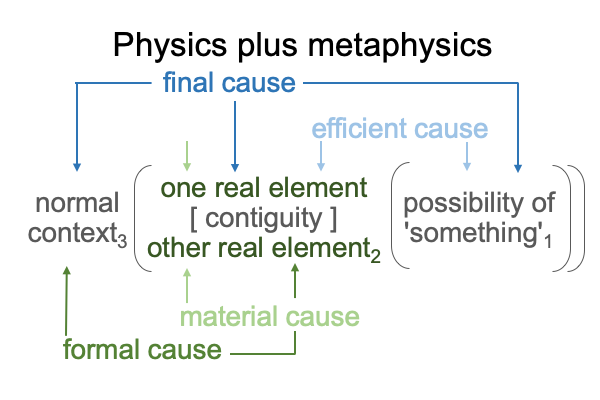

0817 In this case, the human agent, directly, as the pack-leader for Daisy and indirectly, for the unfamiliar dog who innately senses that humans are better pack-leaders than any creature walking on four legs, makes a meaningful decision.

If only that were true.

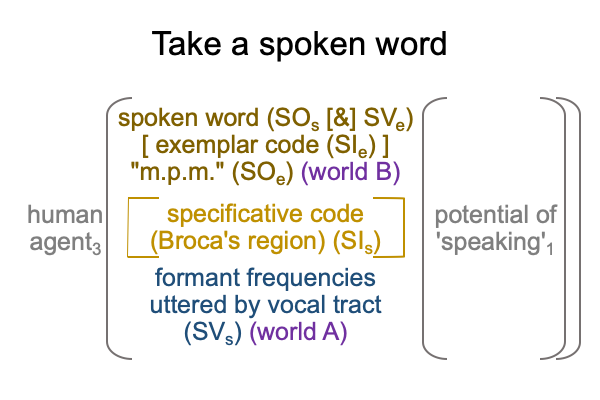

The subsequent action is an interventional sign-vehicle (SVi) that must be regarded as an expression of intention (SOi) in the normal context of canine pack-leader3 as agent3 and ‘final causality’1 or ‘intention’1 (SIi).

0818 Both Daisy and the unfamiliar dog accept the message (SVs) that my expression of intention (SOi) extends.

Indeed, if one is not a semiotician, then my actions of pulling Daisy’s chain and force-marching a retreat (SVi) constitutes the real (semiotic) event (SVs) that initiates semiotic agency.