Looking at Betsy DeVos’s Book (2022) “Hostages No More” (Part 3 of 8)

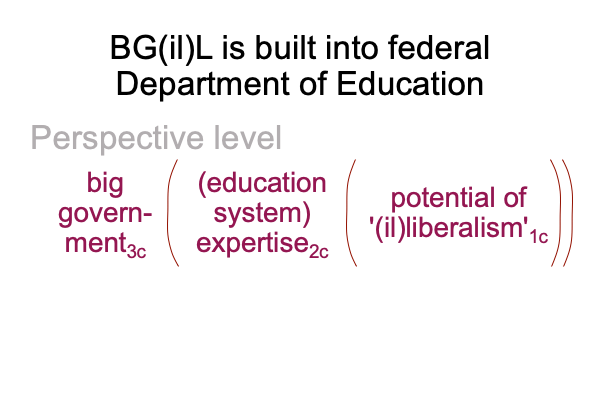

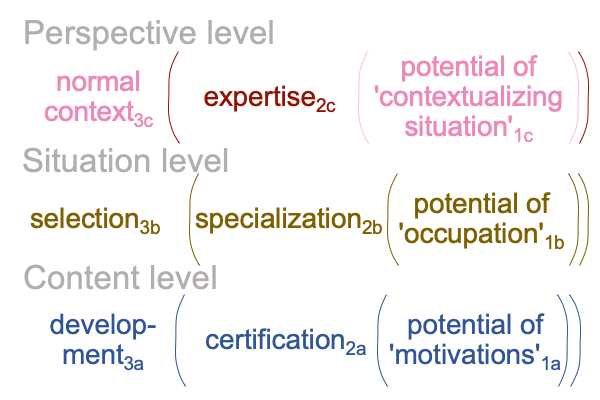

0011 The prior blog provides a glimpse into the perspective-level actuality2c that contextualizes America’s established BG(il)L education system. Here is how experties2c fits into the picture.

0012 The perspective-level normal context3c and potential1c are not obvious. The perspective-level actuality2c is.

Expertise2c virtually brings specialization2b into relation with the potential of certification2a. This is obvious.

The perspective-level normal context3c and potential1c are not so obvious, because the situation- and content-level normal contexts, as well as the potentials, confound the individual, the institution and the government.

0013 Here is a picture.

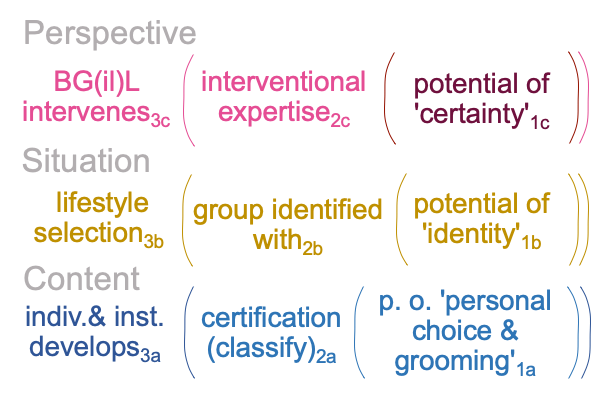

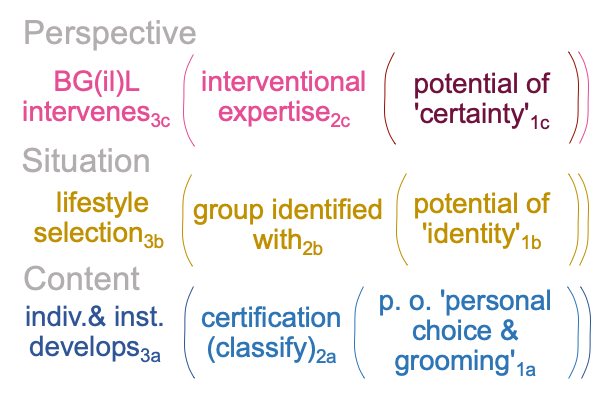

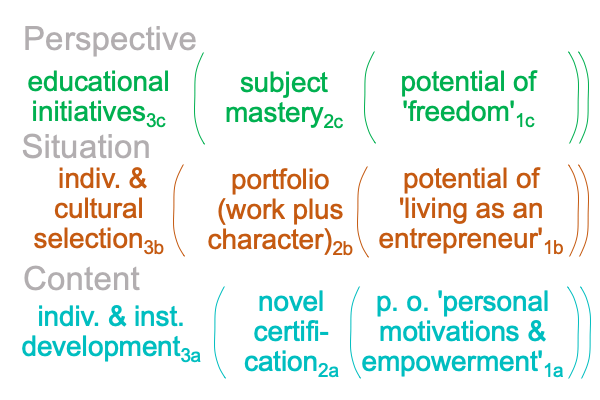

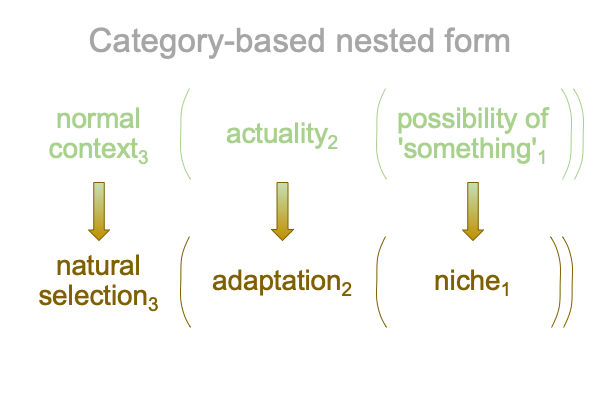

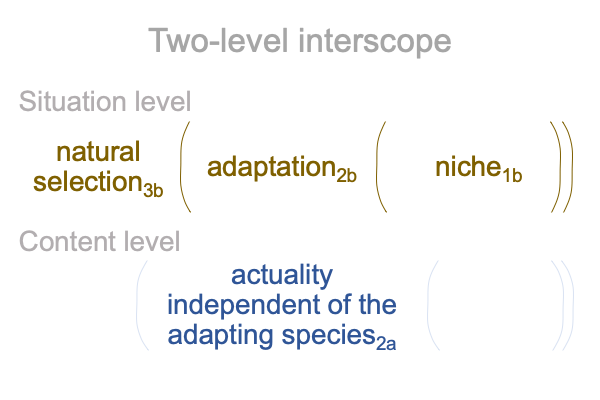

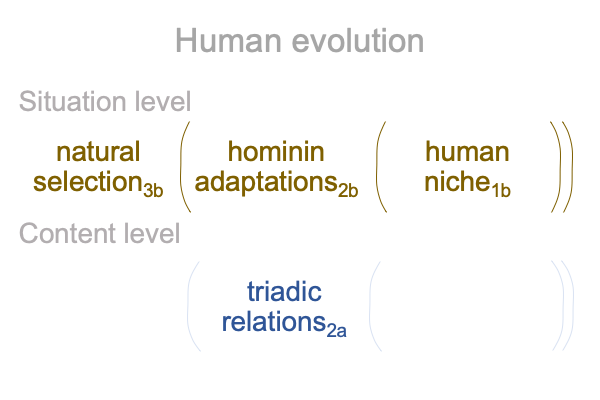

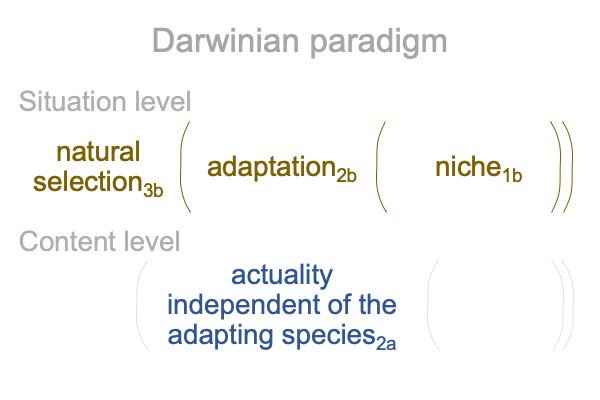

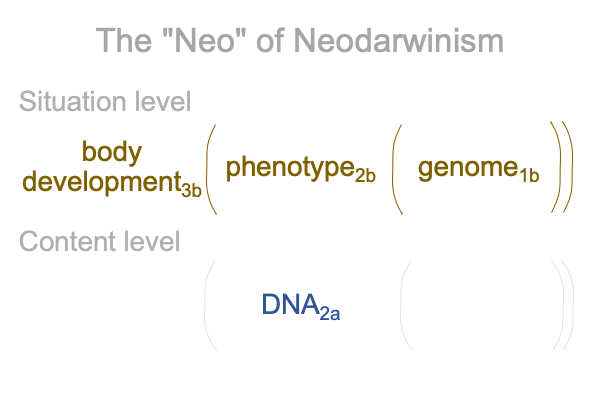

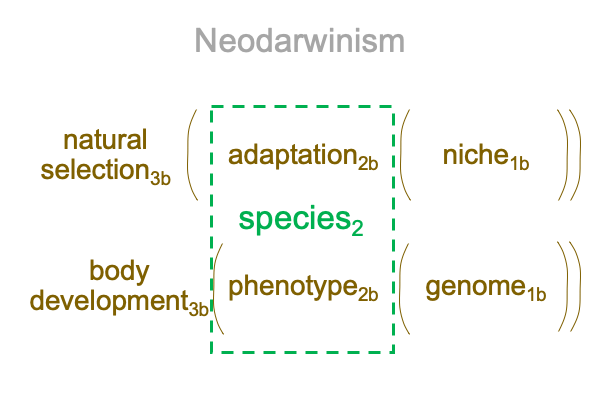

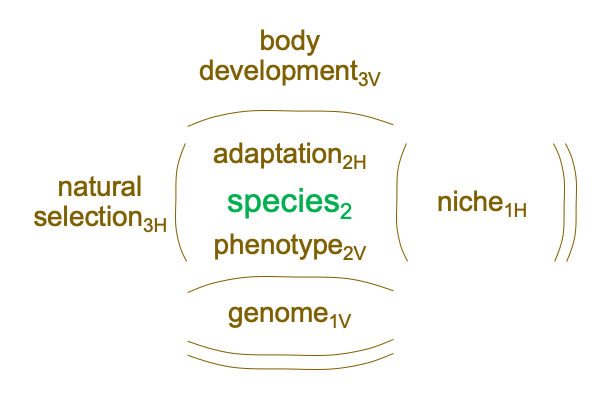

0014 The perspective-level virtually brings the situation-level into relation with the potential of the content-level. In this instance, “virtual” could mean either “in simulation” (the modern option) or “in virtue” (the scholastic option).

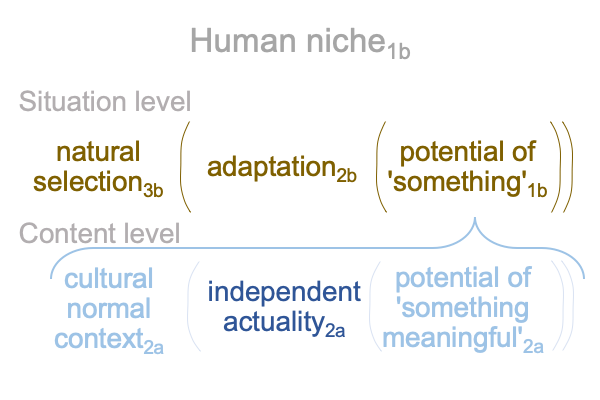

0015 For actuality, expertise2c virtually brings specializations2b into relation with the potential of certification2a.

For the column of normal contexts, a BG(il)L perspective3c virtually brings individual and cultural selection3b into relation with the potentials of individual and institutional development3a. The perspective-level normal context3c must embody the government1a that appears in the content-level potential1a. The normal context3c also must set the stage for cultural selection3b, in regards to both individuals (who are selected for specialization2b) and institutions (who are selected for providing the education leading to certification2a).

Betsy DeVos says, over and over, that the Federal Department of Education is concerned about institutions (such as colleges, school districts, administrators and unionized teachers), rather than students. They are interested in processes that provide instructions leading to certification (for students motivated to fit into an already established menu of specializations). They could not care less about what students really need. They presume that students need to conform to their programs, their goals and their definition of what students must know in order to acquire certification.

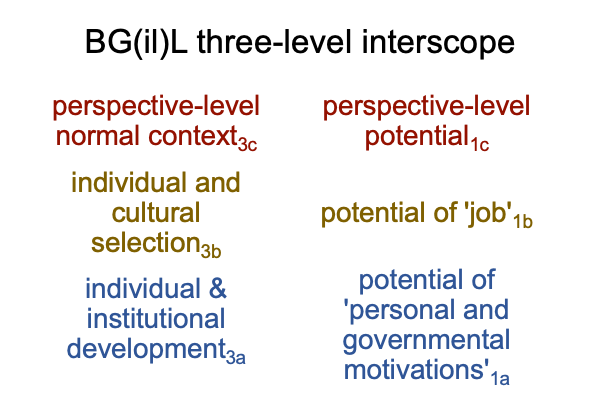

0016 What label applies to the perspective-level normal context3c?

Would the term, “big government”, suffice?

0017 The perspective-level potential1c virtually contextualizes jobs1b, while jobs1b virtually situate personal and governmental motivations1a. What is the nature of this perspective-level potential1c? First, it defines jobs1b through regulatory controls. For example, a government may decree that only certain specializations2b (which much be certified2a) are allowed to perform certain tasks… er… jobs1b. Second, governmental motivations1a are taken for granted by people motivated1a to become specialized2b in order to obtain well-defined jobs1b.

In other words, the government maintains regulatory control of the situation (jobs1b) while providing the appearance that the individual is free to choose his or her own destiny (personal motives1a). In the process, government motivations1a are simply taken for granted and not contested. After all, it would not be sensible to contest government motivations1a. Most students and parents have no clue that their ambitions are pursued in conformity with government agendas.

0018 What label applies to the perspective-level potential1c?

Would the term, “(il)liberal”, do the trick?

Well, what does (il)liberal mean?

Liberalism elevates individual autonomy… say, sovereignty… above various authorities, including religious institutions, businesses, civic networks, military organizations, governments, and so forth. So, the prefix, (il), is hidden because there is an unacknowledged exception. The government is excepted. So, (il)liberalism provides the appearance of individual autonomy while maintaining government regulatory control.

The virtual nested form in firstness says, “(Il)liberalism1c virtually brings jobs1b into relation with the potentials of personal and governmental motivations1a.”

0019 Here is the perspective-level nested form for BG(il)L education.