Looking at Mariusz Tabaczek’s Book (2019) “Emergence” (Part 4 of 22)

0024 What is going on?

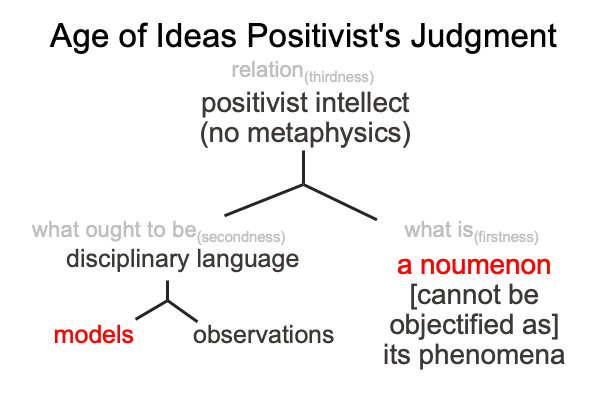

Here is a picture of Positivist’s judgment in the modern Age of Ideas. The name of the age is coined by Thomist and semiotician John Deely in his masterwork, Four Ages.

0025 What is Tabaczek obviously missing in his quest?

Has he not been informed that the positivist intellect does not allow metaphysics?

Apparently not.

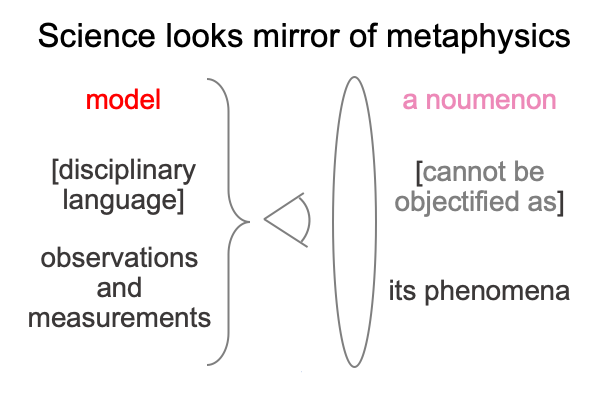

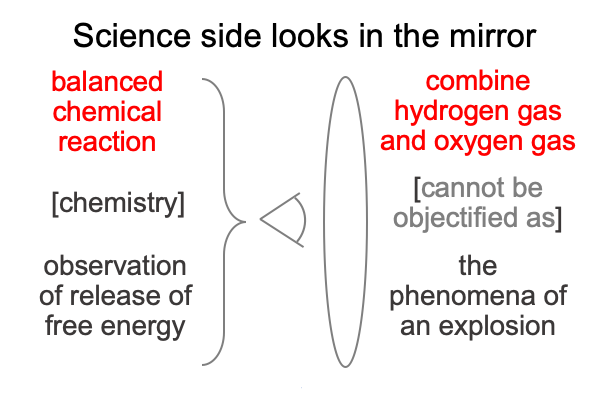

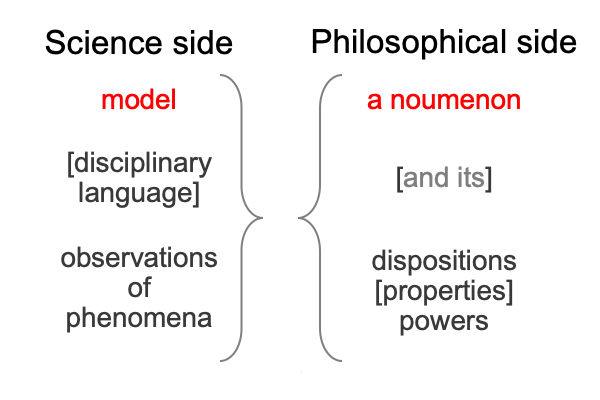

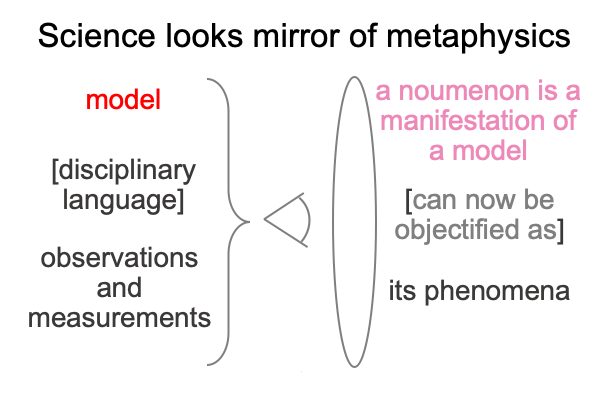

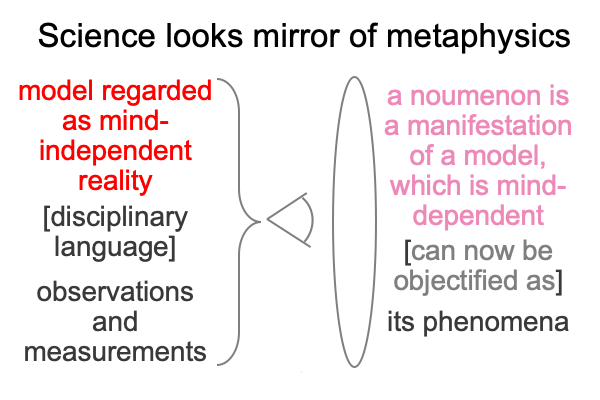

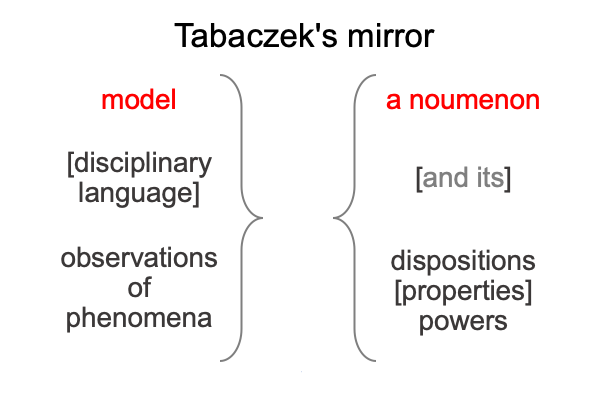

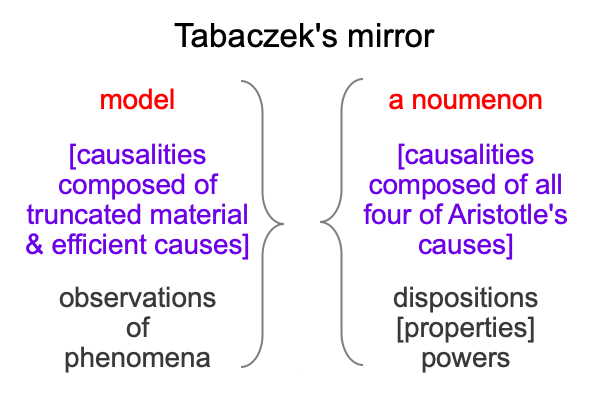

0026 There are two points of illumination in the Positivist’s judgment: the model and the noumenon. The scientist extols the model, because the model (theoretically) permits one to predict and control phenomena. Furthermore, the noumenon is the element that is most susceptible to metaphysical propositions. The positivist intellect bans metaphysical propositions, leaving open the question asking, “What is the nature of the thing itself?”

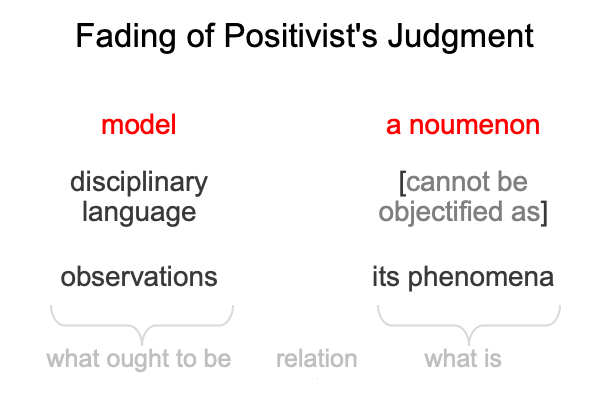

0027 As soon as Tabaczek ignores (or does not acknowledge) the relational importance of the positivist intellect for everyday science, he effectively deprives the demanding creature of its meaning, presence and message. The positivist intellect loses its definition. It dies. And, Tabaczek does not even know that he inadvertently dispatched the normal context for everyday science.

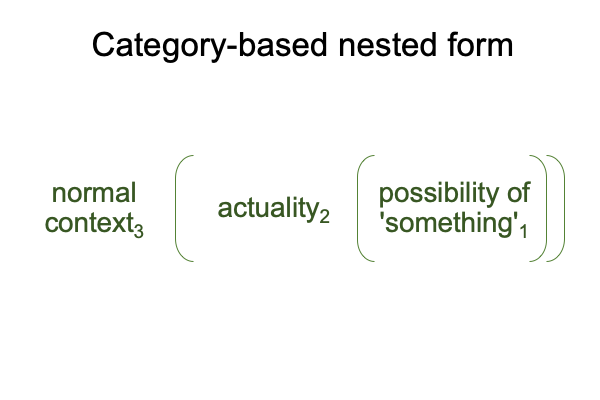

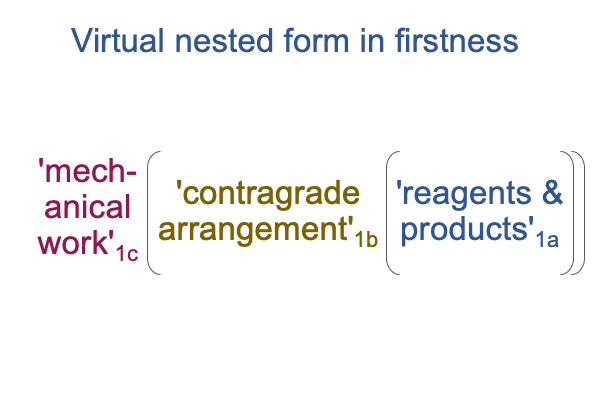

Remember, the actionable judgment unfolds into a category-based nested form on the basis of its assigned categories. The Positivist’s judgment unfolds into the following: The normal context of the positivist intellect3 brings the actuality of the empirio-schematic judgment2 into relation with the potential of phenomena1. Well, it’s not just the potential of phenomena1. It is the potential of a noumenon [that cannot be objectified as] its phenomena1.

0028 Uh-oh.

Tabaczek unwitting relieves the positivist intellect of its duties.

What happens next?

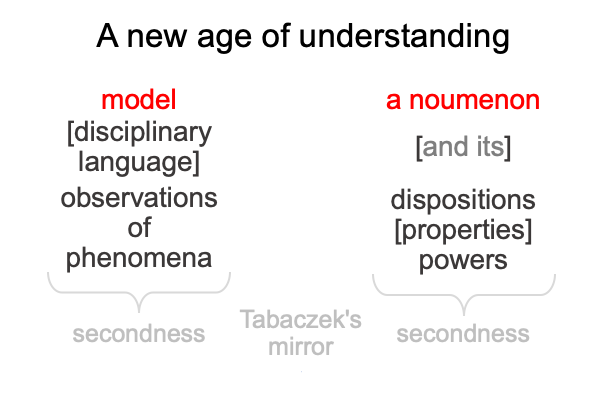

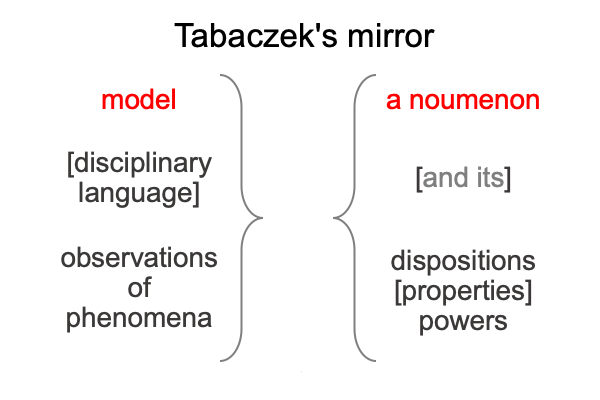

The elements of the Positivist’s judgment lose their relationality and the two points of illumination rise to the top of the diagram.

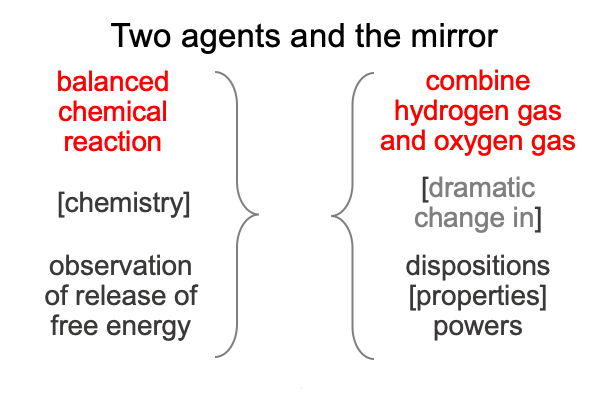

0029 Note the appearance of each side of the disassembled relation.

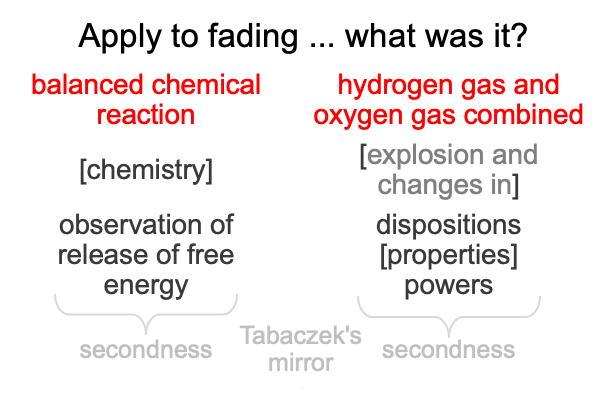

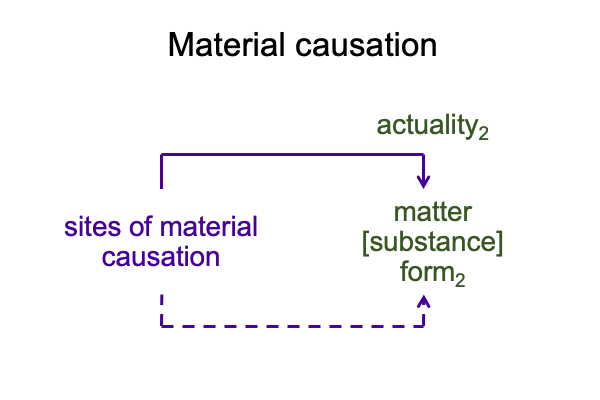

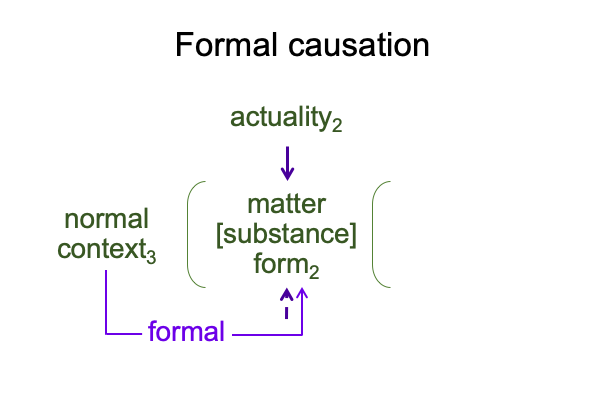

On one side, the empirio-schematic judgment slides from Peirce’s category of thirdness (judgments are triadic relations) to Peirce’s category of secondness (consisting of two contiguous real elements). The two real elements are the model and observations (and measurements). The contiguity is the disciplinary language.

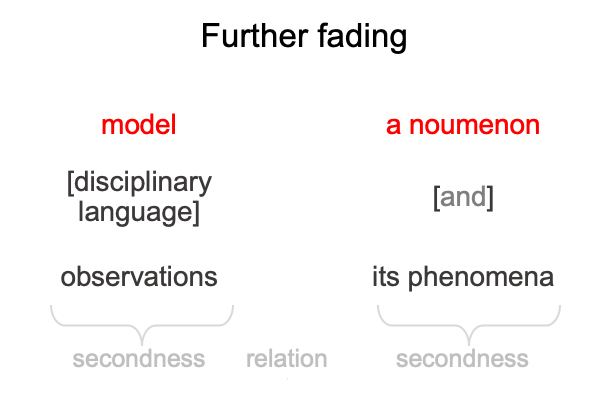

On the other side, the hylomorphe, a noumenon [cannot be objectified as] its phenomena, which was assigned to firstness, takes on the character of secondness. How so? For the scientist, the noumenon [cannot be objectified as] its phenomena. For Tabaczek, the noumenon [has] its phenomena, so the contiguity between the two real elements is [and].

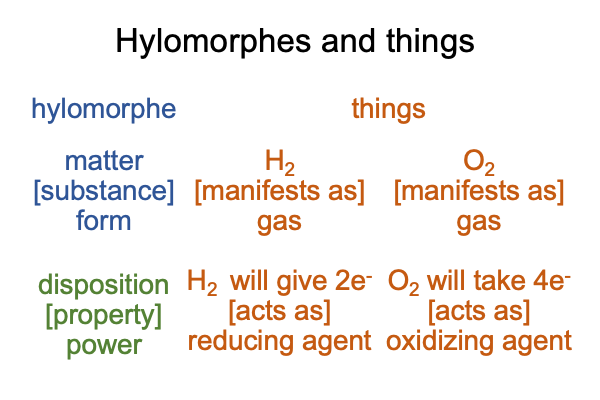

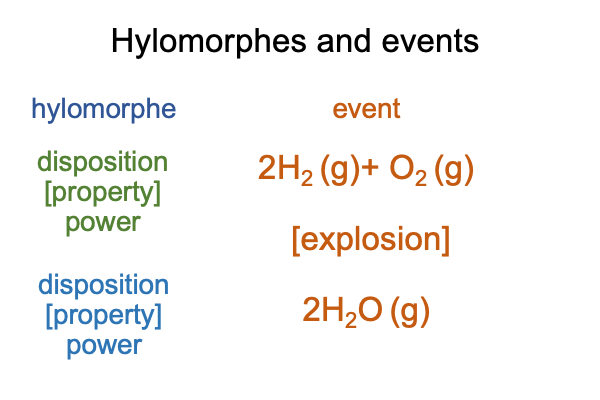

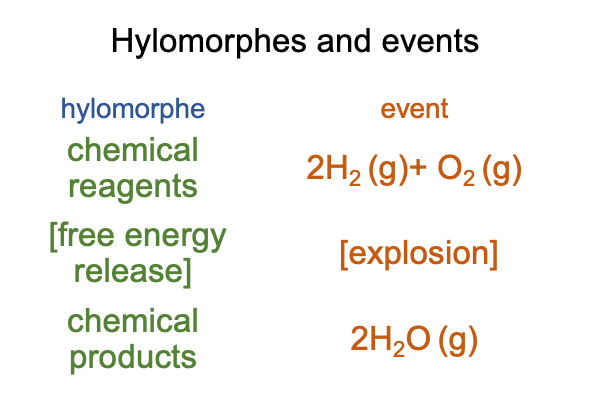

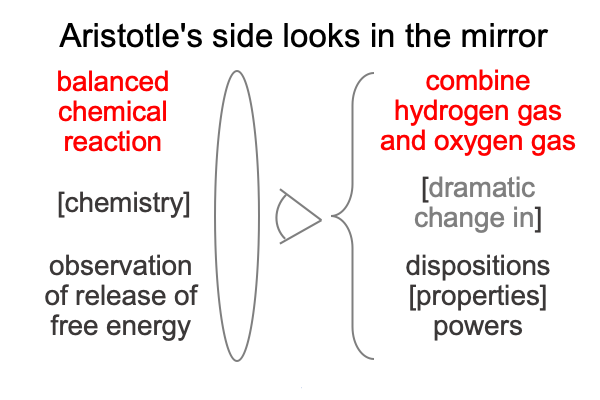

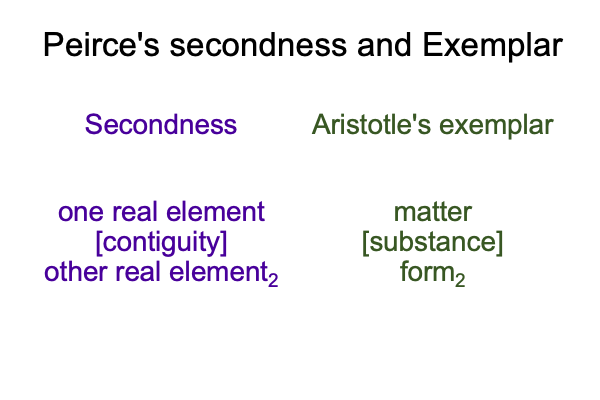

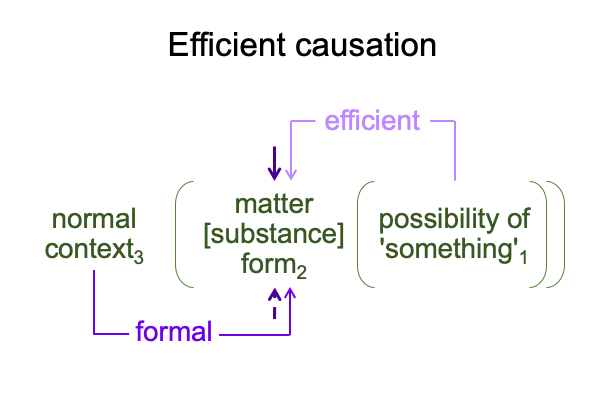

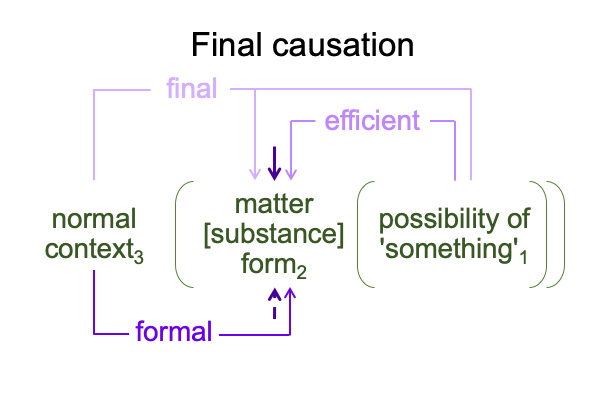

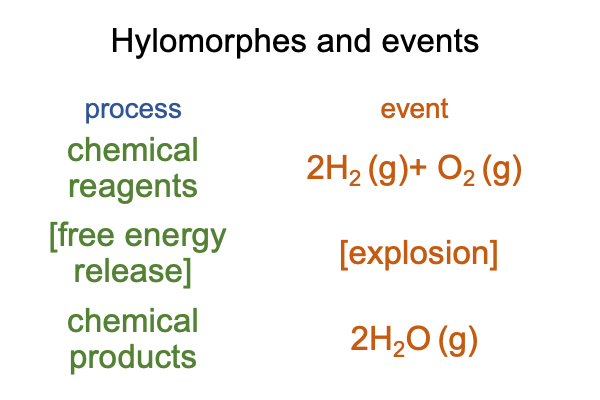

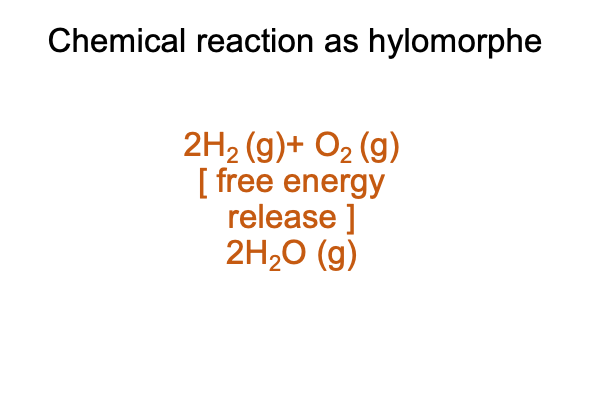

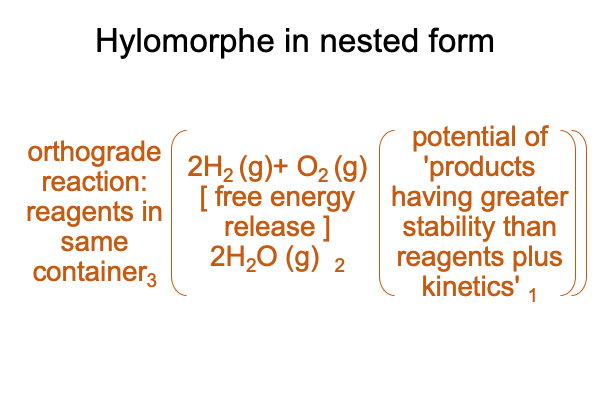

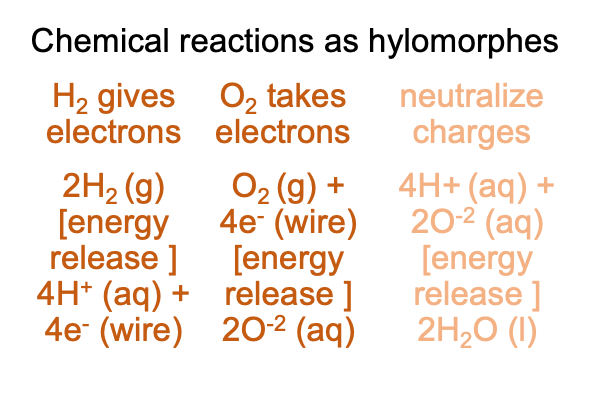

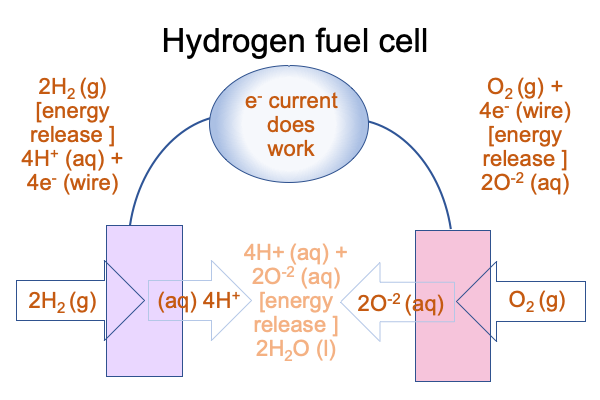

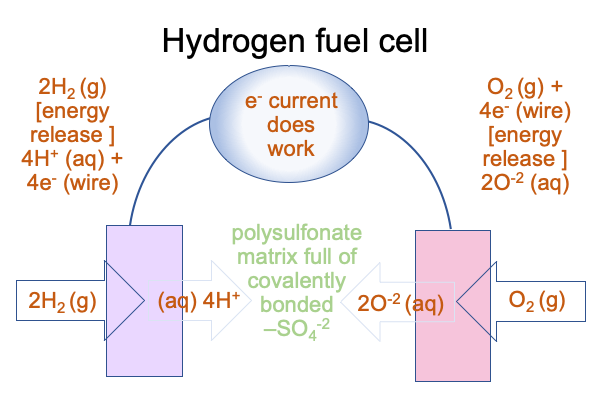

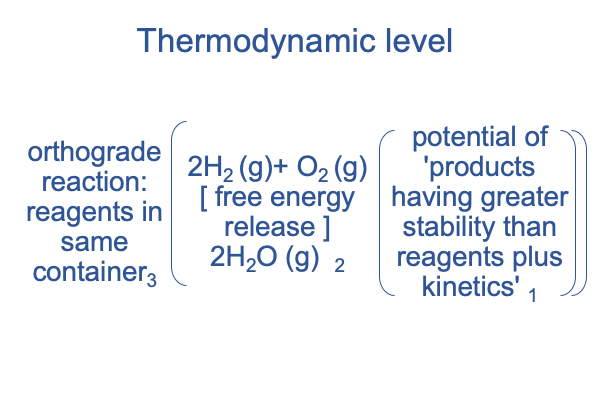

0030 In the introduction, Tabaczek devotes a lengthy section (1.6.2.2) to hylomorphism. To me, Aristotle’s hylomorpheexemplifies Peirce’s category of secondness. Secondness consists of two contiguous real elements. For Aristotle, the real elements are matter and form. When I place the contiguity in brackets, Aristotle’s hylomorphe is rendered as matter [contiguity] form. Then the question arises, asking, “Do I have a label for the contiguity?” I have a guess. The label for the contiguity between matter and form is [substance]. Consequently, for me, Aristotle’s hylomorphe is matter [substantiates] form.

Who would have imagined?

0031 Does the association between hylomorphe and Peirce’s secondness apply to the above figure?

Yes. The contiguity between model and observations describes the substance of each scientific discipline, that is, its specialized language. Also, the contiguity of between a noumenon [and] its phenomenon is a substance similar to the contiguity between a whole [and] its parts.

0032 What does this imply?

Peirce’s secondness adds versatility to Aristotle’s hylomorphe.