Looking at John Deely’s Book (2010) “Semiotic Animal” (Part 22 of 22)

0172 Deely concludes with a sequel concerning the need to develop a semioethics.

The meeting of the two semiotic animals in the previous blog is a case study.

Surely, that brief clash of objective worlds entails ethics, however one defines the word, “ethics”.

Perhaps, the old word for “ethics” is “morality”.

0173 Deely publishes in 2010.

Thirteen years later, his postmodern definition of the human takes on new life. This examination shows how far semiotics has traveled, swirling around the stasis of a Plutonic publishing world where Cerebus guards the gates. Please throw a sop to the editors in order to publish, rather than perish. While academics guard the way to the underworld of professional success, Deely looks down from the heavens above.

And what does he say?

Humans are semiotic animals.

0174 Okay, I have to correct myself.

I don’t know whether Deely is looking down from a heavenly perch.

Surely, many will sheepishly testify to his devilish, as well as his angelic, qualities.

As a shepherd, he is always trying to lead his rag-tag flock of semioticians, explorers and Thomists. He gets so far as to impress upon every one in his flock the validity of his claim that humans are semiotic animals.

0175 Razie Mah takes that lesson to heart and asks, “If humans are semiotic animals, then how did they evolve?”

The resulting three masterworks are available at smashwords and other e-book venues.

An Archaeology of the Fall appears in 2012, followed by an instructor’s guide.

How to Define the Word “Religion” appears in 2015, followed by ten primers.

The Human Niche appears in 2018, along with four commentaries.

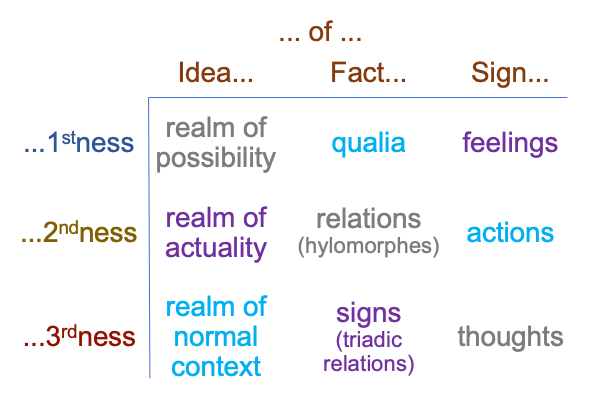

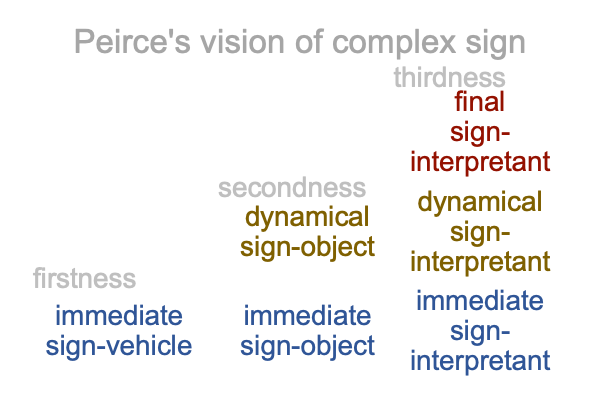

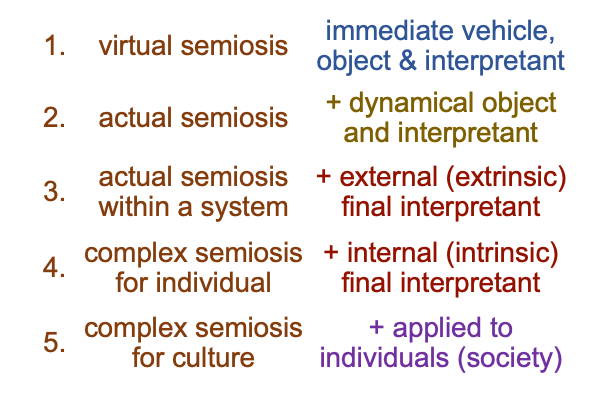

As it turns out, no contemporary scientist takes Deely’s claim seriously. Yet, the implications are enormous. If humans are semiotic animals, then triadic relations must be key to understanding human evolution.

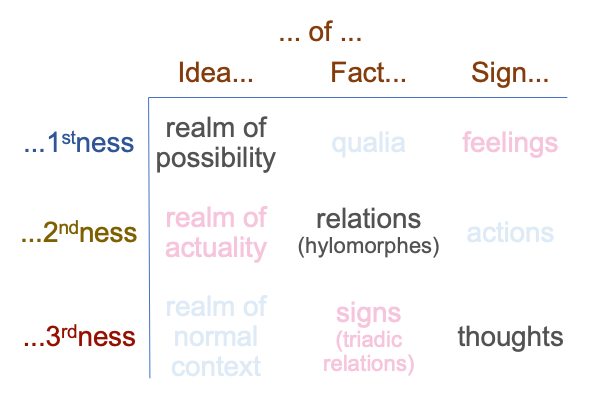

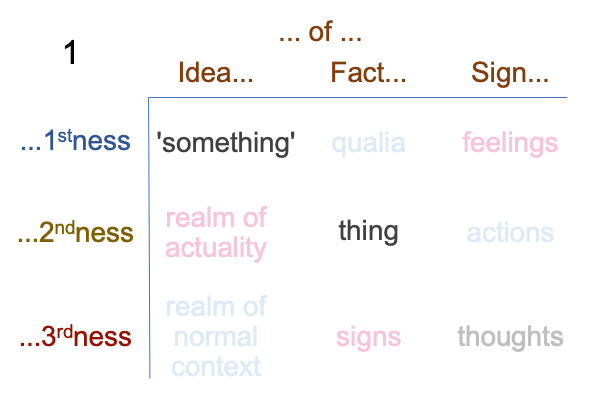

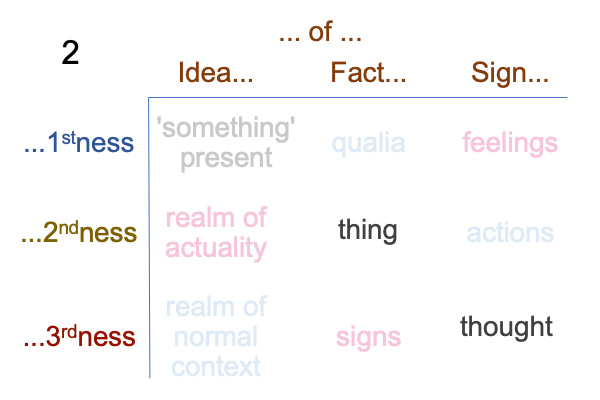

0176 This examination of Deely’s book takes that lesson one step further.

The specifying and exemplar signs step out from Comments on John Deely’s Book (1994) New Beginnings as expressions of premodern scholastic insight.

The interventional sign steps out from Comments on Sasha Newell’s Article (2018) “The Affectiveness of Symbols” and establishes a postmodern life of its own.

0177 Humans are semiotic animals and how we got here shines like a revelation.