Looking at Abir Igamberdiev’s Chapter (2024) “Evolutionary Growth of Meanings…” (Part 1 of 4)

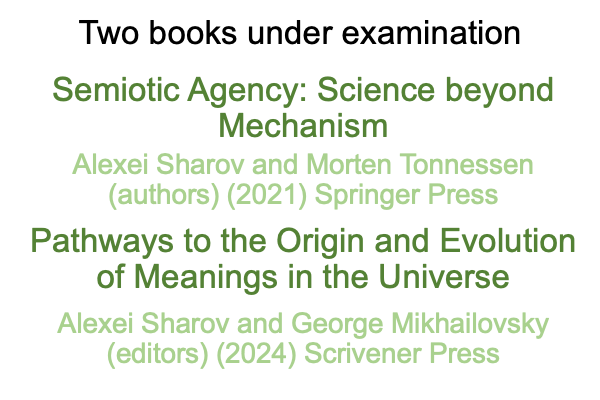

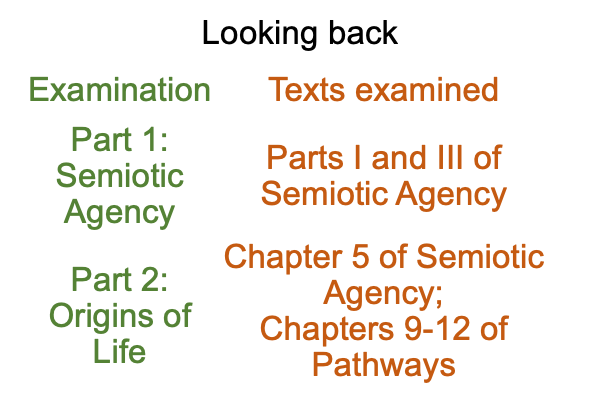

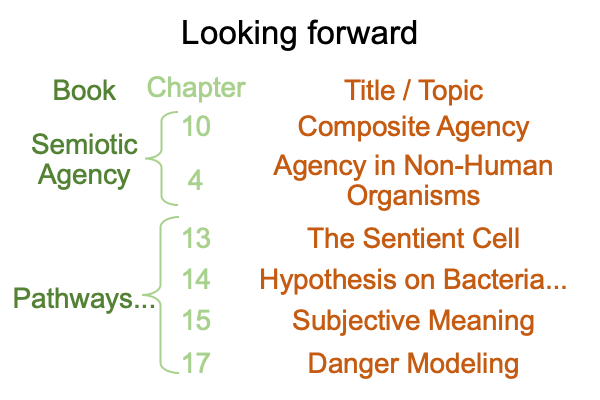

0434 The text before me is chapter twelve in Pathways to the Origin and Evolution of Meanings in the Universe (2024, edited by Alexei Sharov and George E. Mikhailovsky, pages 265-278). The full title is “Evolutionary Growth of Meanings in the Relational Universe of Intercommunicating Agents”. The author is a biologist at the Memorial University of Newfoundland, at St. John’s.

0435 The introduction places the term, “agent”, on stage.

How does one know whether “an agent” is an agent?

Well, the agent should be obvious. An agent is physical. An agent is the repository of – what Aristotle calls – “final causality”. Final causality associates to another metaphysics-laden term, “teleology”.

What is the meaning of this term, “repository”.

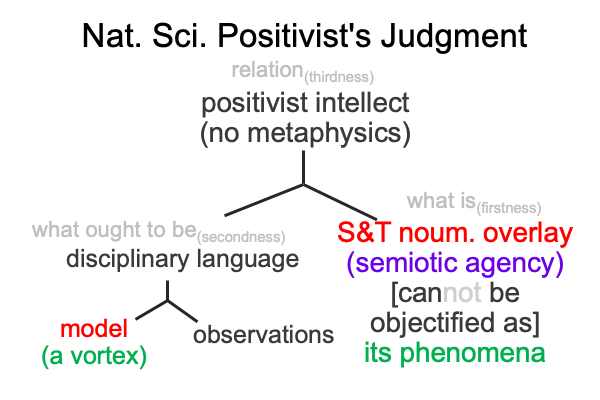

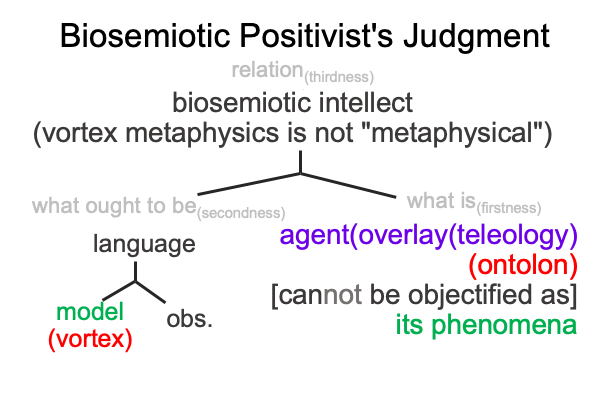

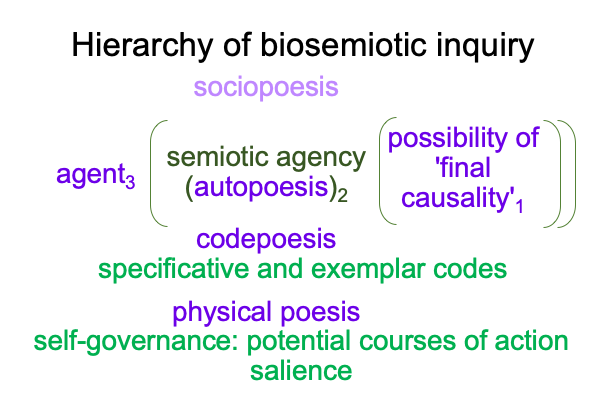

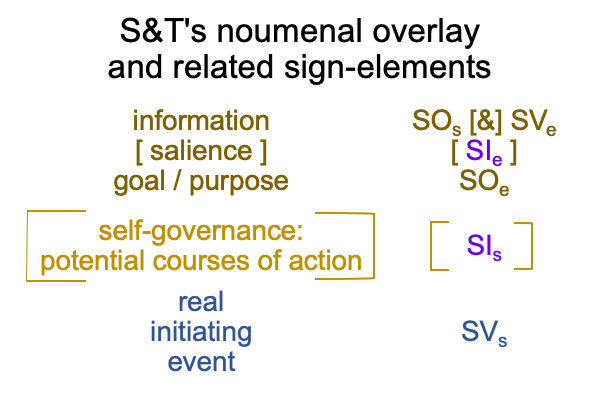

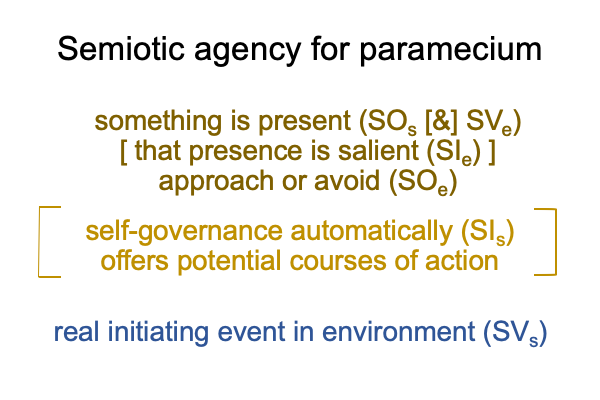

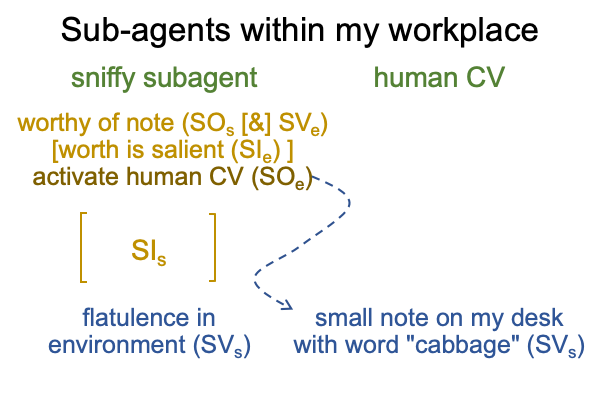

0436 I only ask this because the thing that we encounter in science associates to what is for the Positivist’s judgment. Sharov and Tonnessen’s noumenal overlay pertains to what is, and it describes semiotic agency. Semiotic agency (as the noumenon) gives rise to phenomena that are observed and measured by biologists, then the resulting models are attributed, not to agency2 itself, but to the agent3 and the agent’s intentions1 (that is, final causalities).

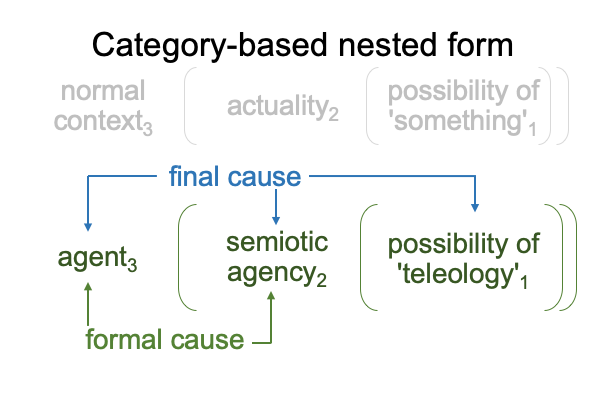

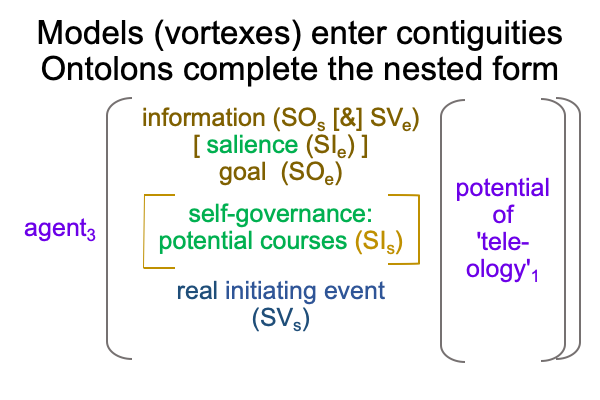

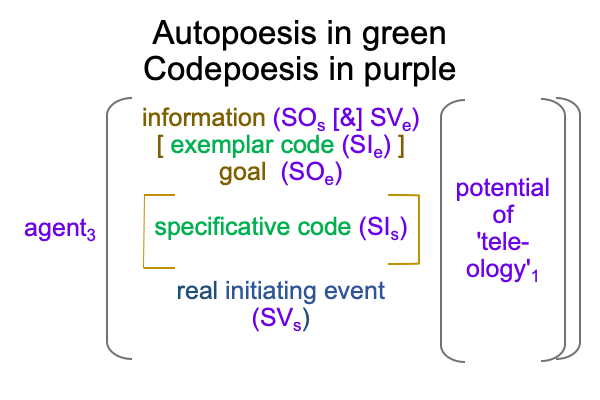

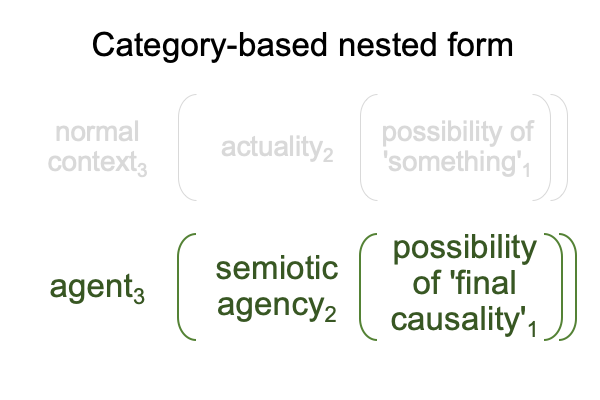

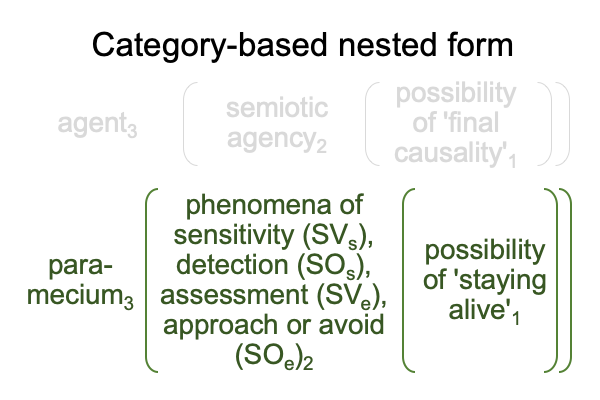

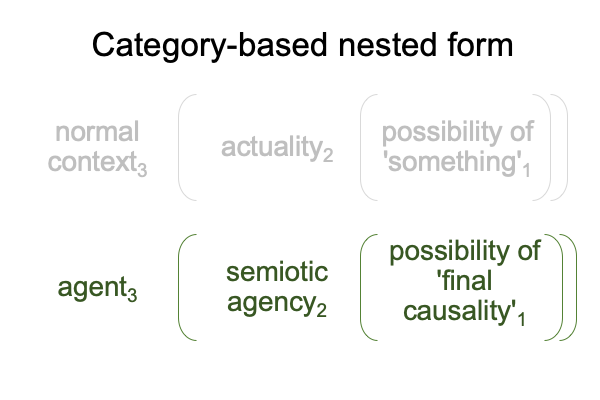

0437 “Repository” plays out as a category-based nested form.

The normal context of an agent3 brings the actuality of semiotic agency2 into relation with the possibilities inherent in ‘final causality’1.

The agent3 puts semiotic agency2 into context. Semiotic agency2 emerges from (and situates) the potential of ‘teleology’1.

These basics are found in A Primer on the Category-Based Nested Form, by Razie Mah, available at smashwords and other e-book venues.

0438 The image of “the agent” as “an obvious repository of final causality” treats the category-based nested form diagrammed above as a thing.

The author presents the image without hesitation, as if that is what human naturally do. Humans not only treat a thing as a thing, but we also treat a corresponding category-based nested form as a thing. Not the same “thing”, but still, a thing.

We observe semiotic agency2. We visualize the agent3 as a physical repository of final causality1.

0439 What does this imply?

Consider the title of the chapter, Evolutionary Growth of Meanings in the Relational Universe of Intercommunicating Agents.

Where do I slip the category-based nested form into this title?

Do category-based nested forms slide into the author’s designation of “relational universe”?

If so, then the substitution brings this examiner face to face with where the author seems to be going, the recovery of Aristotle’s causalities within the milieu of biosemiotics.

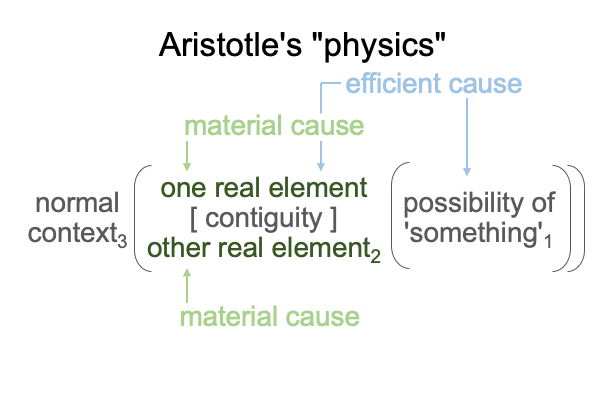

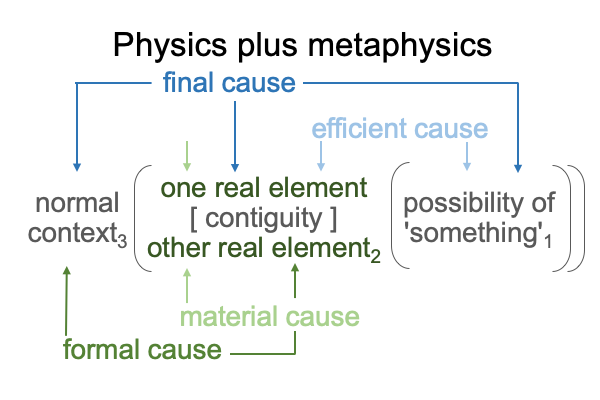

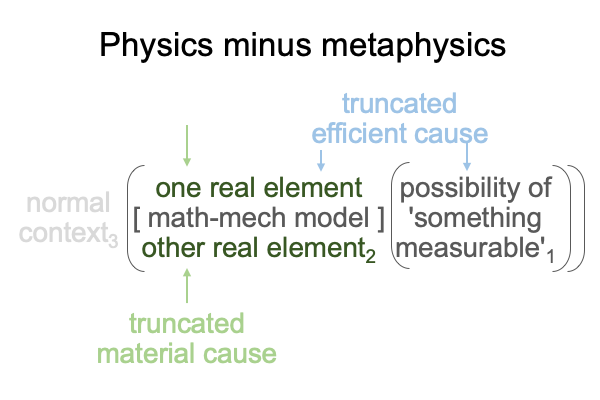

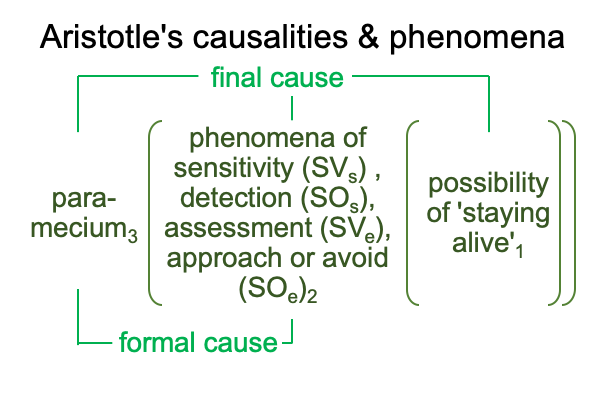

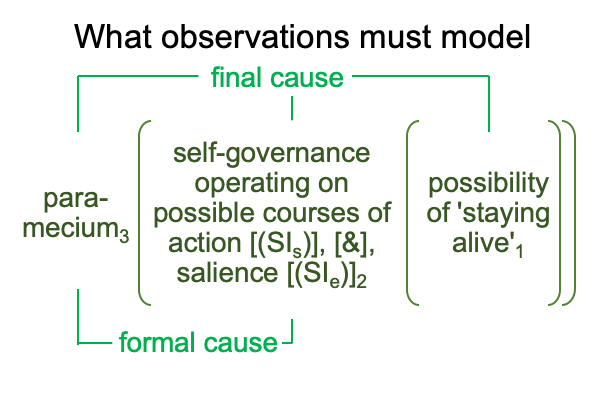

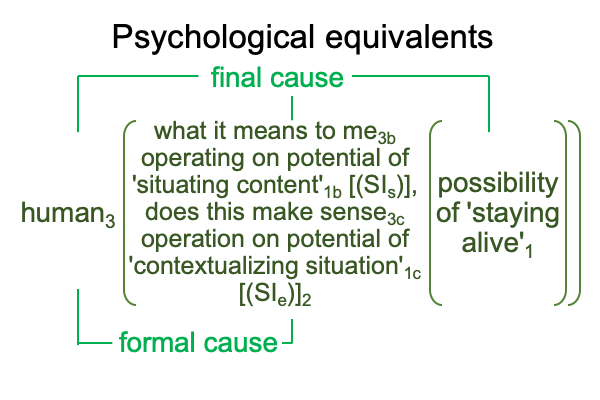

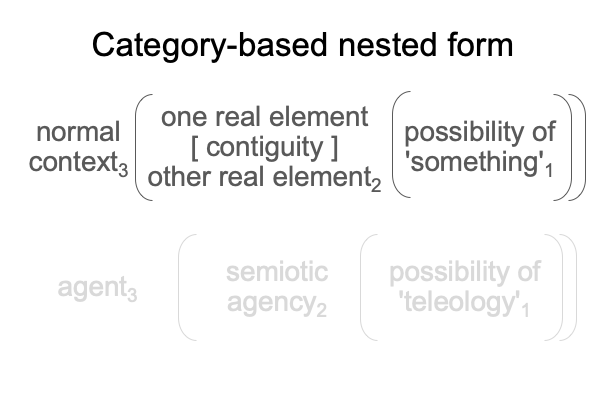

0440 If that is the case, let me present a more hylomorphic version of the category-based nested form.

0441 Notice that actuality2 corresponds to Peirce’s category of secondness. Secondness consists of two contiguous real elements. In the figure, the contiguity is placed in brackets for the purposes of notation.

For example, for Aristotle, when I encounter a thing, the two real elements that come to mind are matter and form. Matter is necessary for presence. Form is necessary for shape. What is the contiguity between matter and form? Here, I snatch a term that has been much abused, because it has been so difficult to grasp. The term is “substance”. I now assign a very specific, technical definition to the term in hand. “Substance” is the contiguity between matter and form.

0442 Aristotle’s hylomorphe is an exemplar of Peirce’s category of secondness.

Thus, the recovery of Aristotle’s terminology in the biosemiotic milieu begins.

0443 Abir Igamberdiev is not the only one to imagine a recovery of Aristotle’s causality in light of the postmodern compromise of the positivist intellect.

Mariusz Tabaczek pursues a recovery in the field of emergence. Emergence endeavors to account for the constellation of higher-order noumena that could not be predicted on the basis of lower-level noumena. Like biosemiotics, the goal is understanding, rather than prediction and control.

See Comments on Mariusz Tabaczek’s Arc of Inquiry (2019-2024) by Razie Mah, available at smashwords and other e-book venues. Much of this commentary may be found in Razie Mah’s blog for March, April and May 2024. Tabaczek’s work is discussed in this examination in points 0276 to 0300.