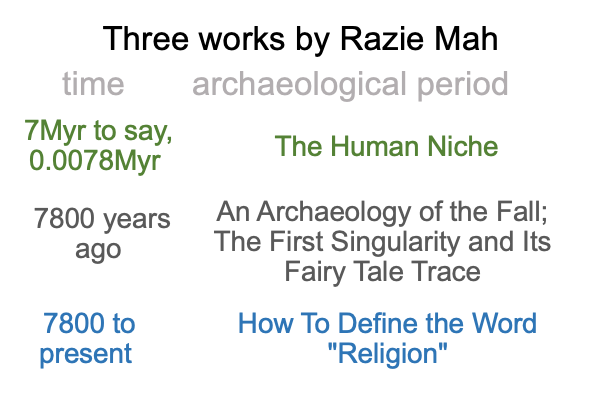

Looking at Michael Tomasello’s Book (2016) “A Natural History of Human Morality” (Part 13 of 22)

0505 Hand talk is very visual.

Today, railroads are very visual.

So, in order to keep on track, railroads will be my metaphor of choice.

Imagine that railroads, everything about them, is owned by a third person, and that person talks to us through… um… the meaning, presence and message of… hmmm… trains and rails and schedules and all that stuff.

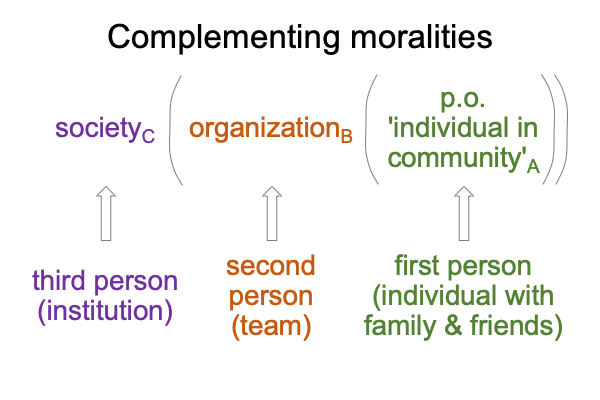

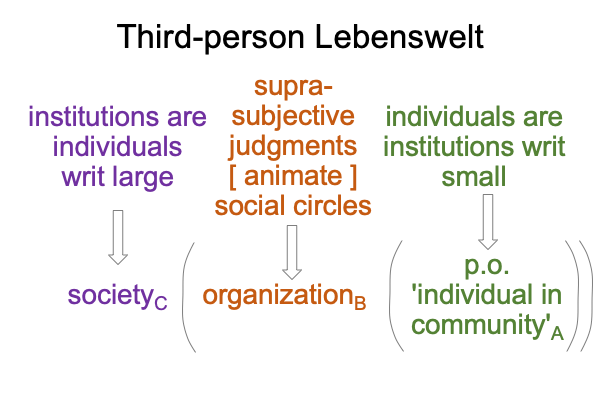

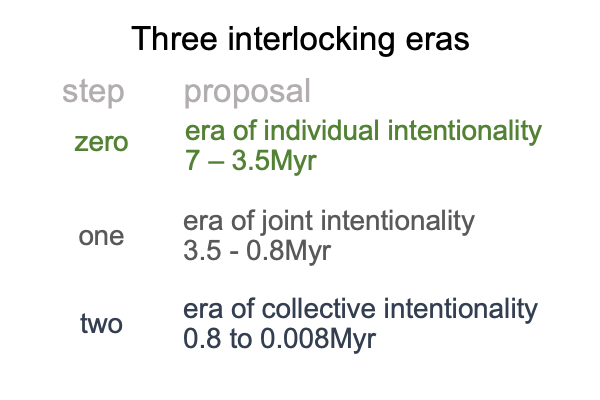

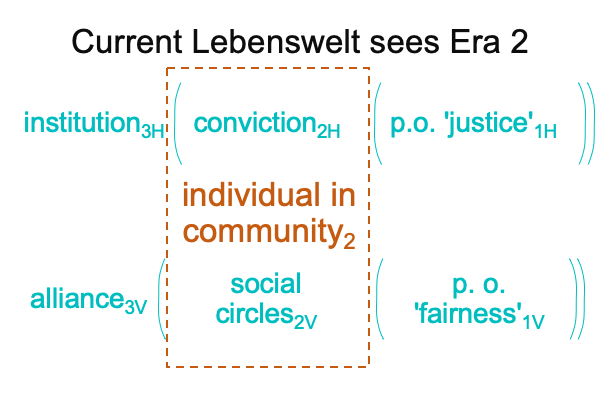

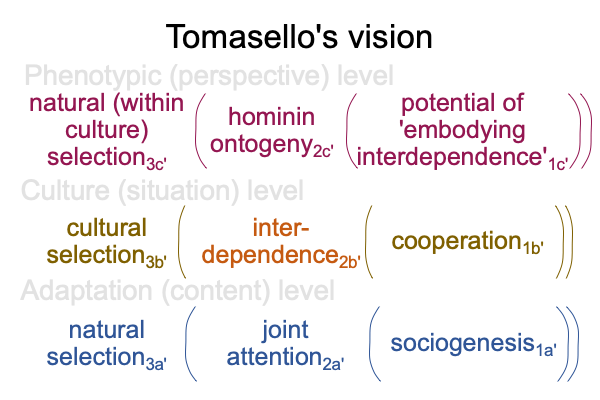

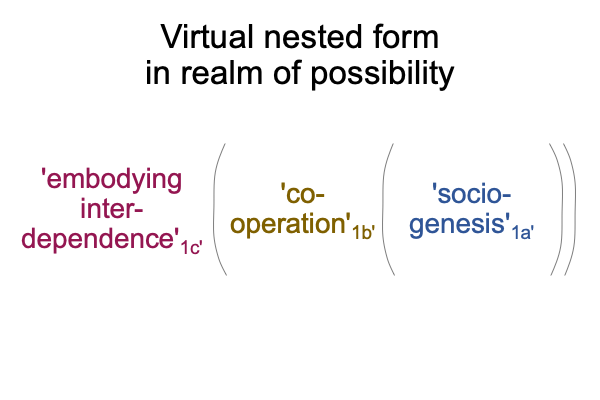

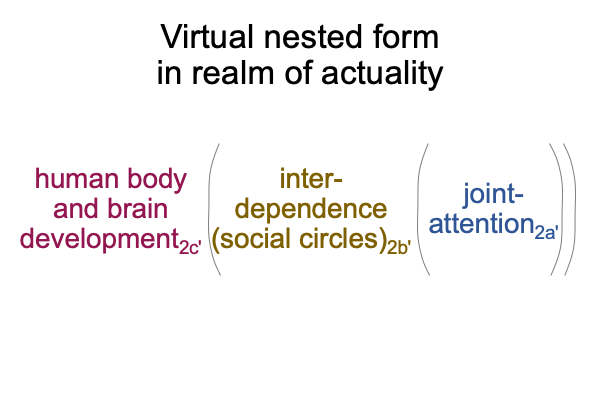

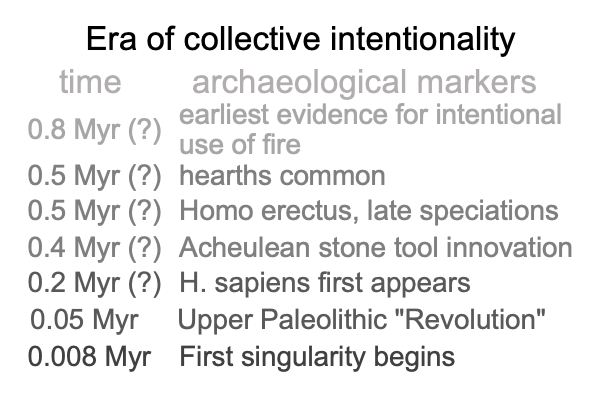

To this third-person track, I attend. The following discussion runs on the third-person track through the same academic territory as chapter four, titled “Objective Morality”. The tracks are as as different as the terms, “objectivity” and “suprasubjectivity”, yet the territory is still the era of collective intentionality.

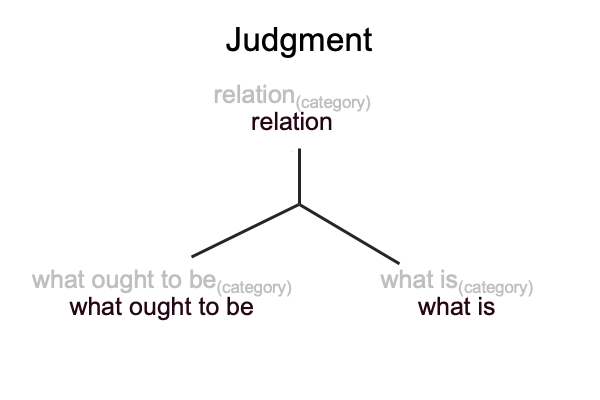

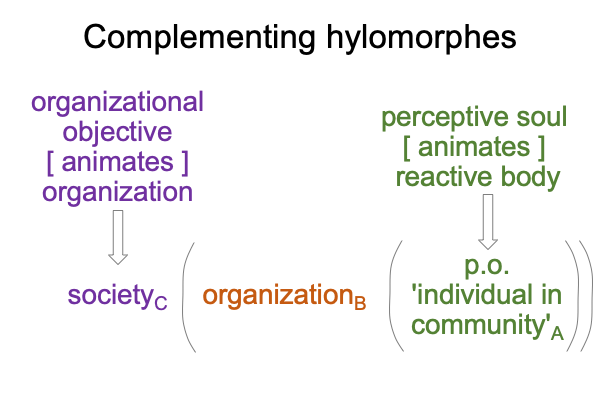

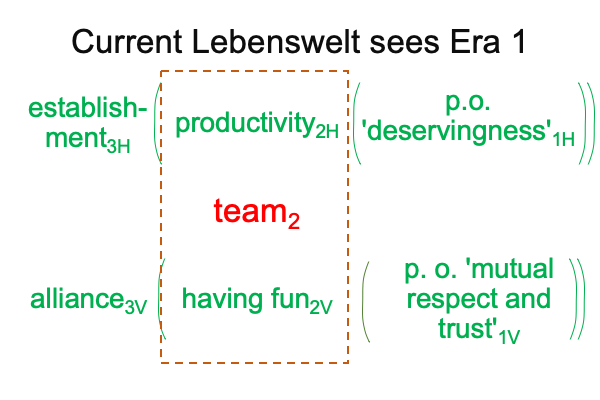

0506 The third-person track begins with an implicit judgment that becomes embodied during the era of joint attention. The team and its organizational objectives are inseparable. They are one thing.

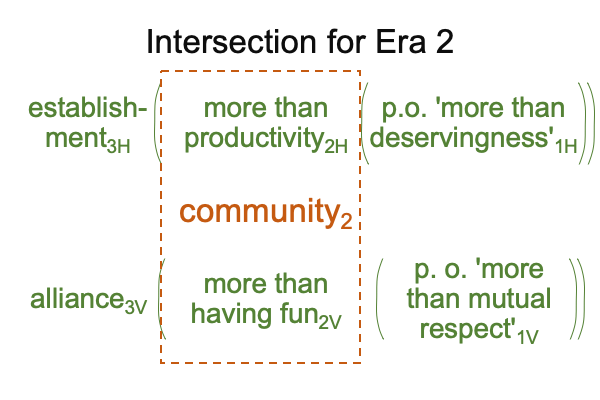

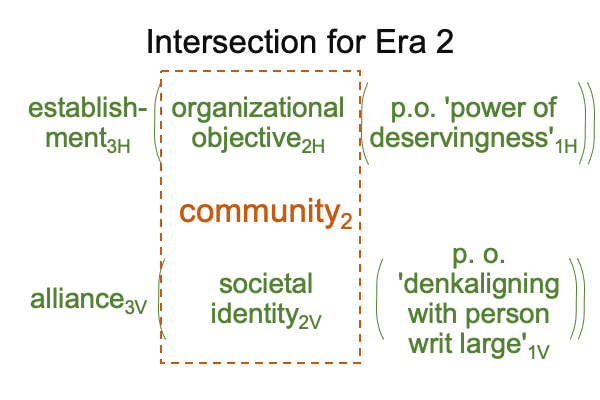

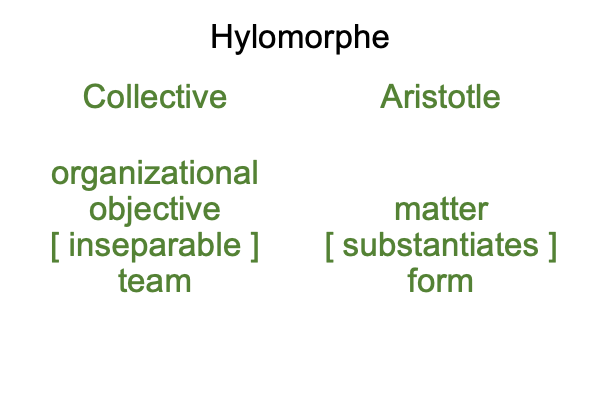

This inseparability coheres to Peirce’s category of secondness. Secondness consists of two contiguous real elements. In this case, the real elements are the team and its organizational objectives. Can I say that the team might associate to having fun2V and the organizational objectives may associate to productivity2H? If so, the contiguity, which stands between the two real elements and therefore gets placed in brackets (for good nomenclature), is the term, [inseparable].

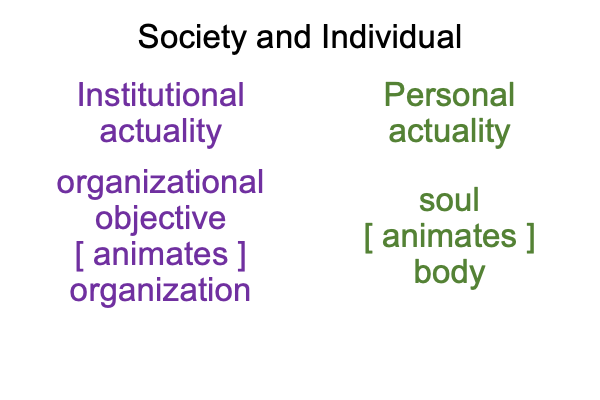

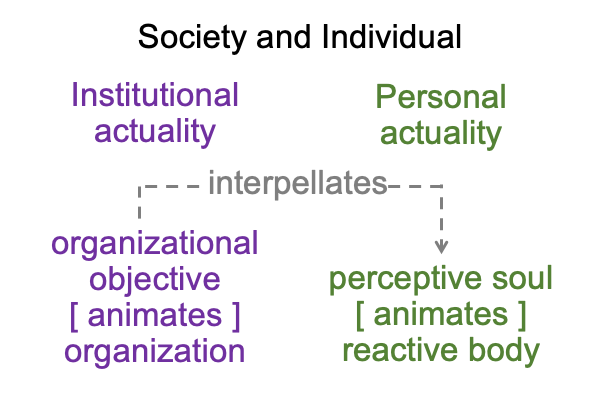

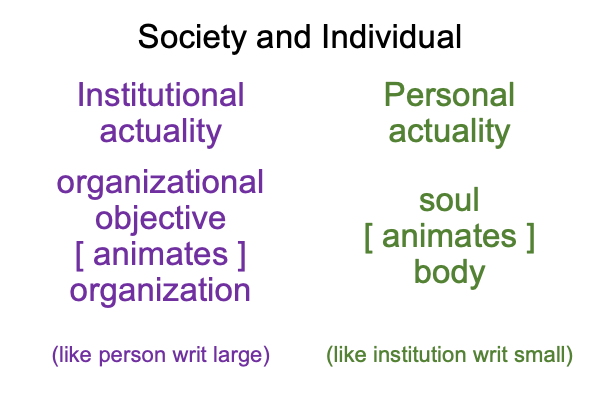

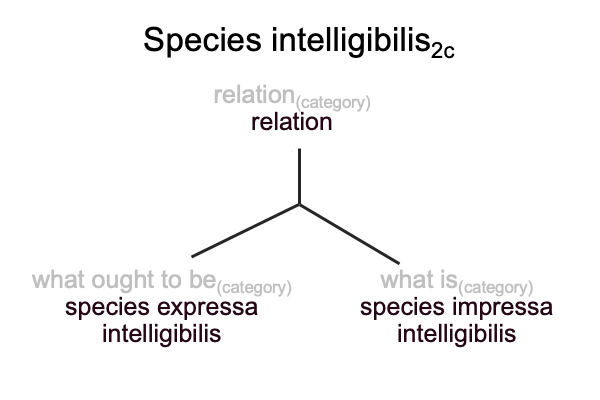

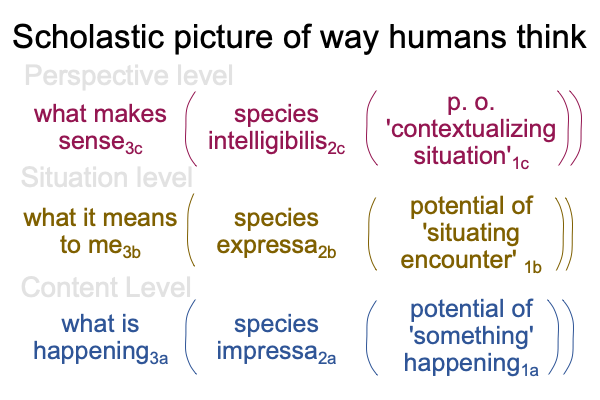

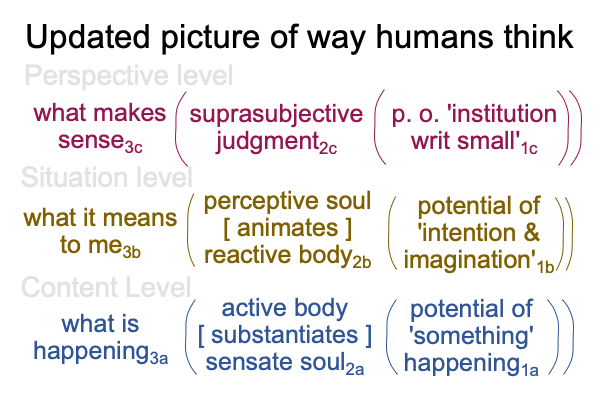

0507 Here is a comparison of the team hylomorphe with Aristotle’s hylomorphe, from which the term, “hylomorphe”, comes. “Hyle” translates from Greek into English as “matter”. “Morphe” translates as “form”.

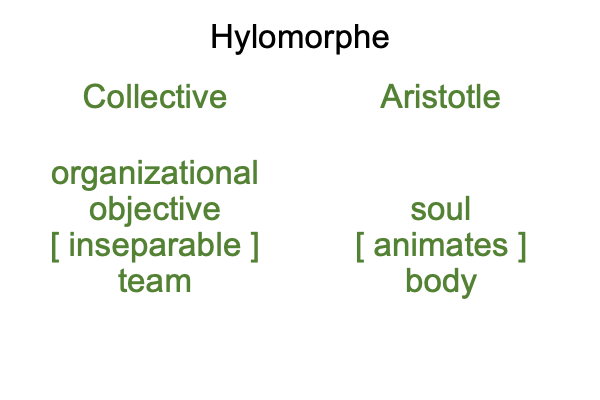

0508 Okay, that will not do. Let me try a different, more medieval sounding, hylomorphe.

0509 Ah, that is better. The contiguity, [inseparable], matches the contiguity, [animates].

Of course, this hylomorphe presents a challenge for modern evolutionary anthropologists who hold the Scottish philosopher, David Hume, in high regard. Only the operations of the team can be observed and measured. The organizational objective must be inferred.

Does this make sense?

A scientist builds models on the basis of observations and measurements of teams. So, I suppose that it is easy for the scientist to imagine that these models correspond to organizational objectives. Such projections are plausible when organizational objectives must be sensible. In other words, the organizational objectives and the team are [inseparable] in ways that make sense. [Animates] relies on sensible construction in the era of joint intentionality.

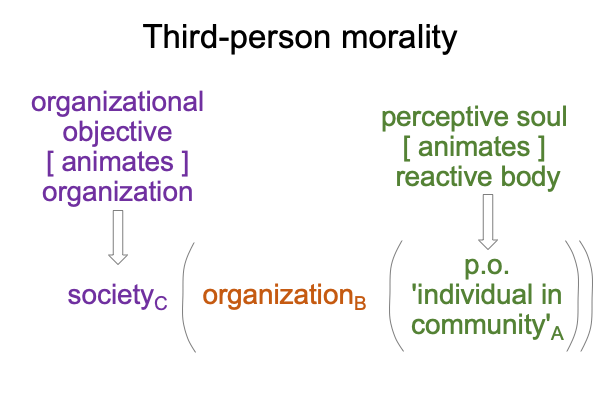

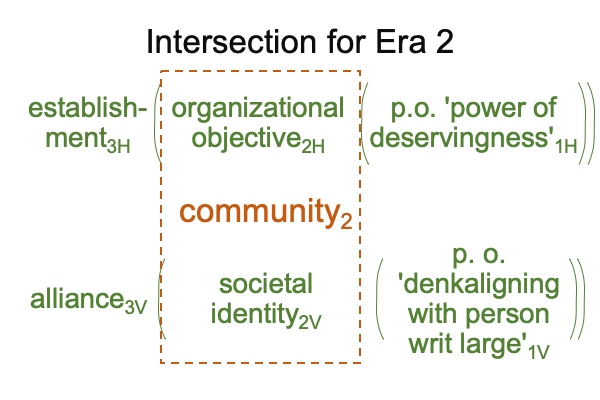

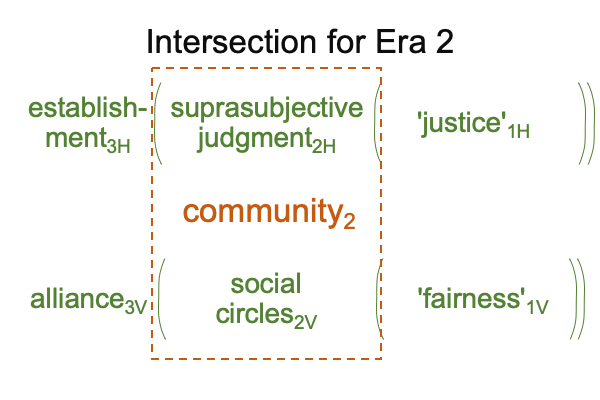

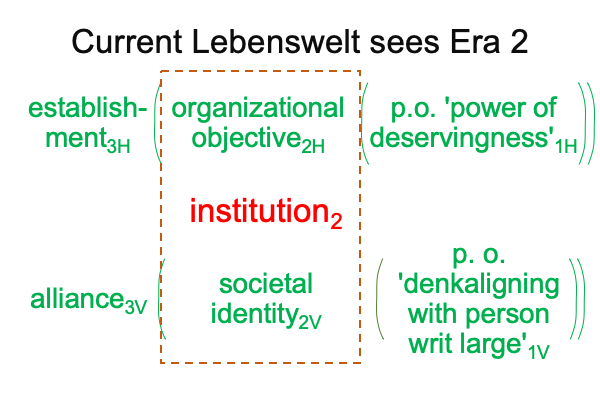

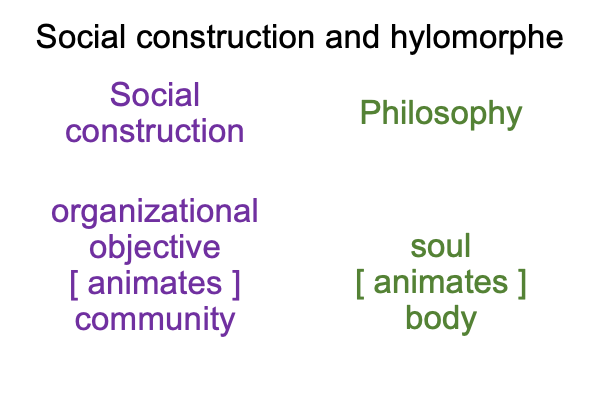

0510 What about the era of collective intentionality?

A community may be regarded as a team of teams. Each team has a single animating organizational objective. Can I label this objective, “subject”? Each team has an animating subject. When I scale up to the community, an organizational objective contains the objectives of each team as animating subjects. Can I label this monstrous organizational objective,“subject”? If I can, then each community has an animating subject that encompasses all the team-subjects and, hopefully, resolves their contradictions.

0511 The slogan, “we work for food”, unfolds into “we work for something more than food”.

The slogan, “we are a web of ‘you-me’ relations” expands into “we are a web of ‘team-team’ relations”.

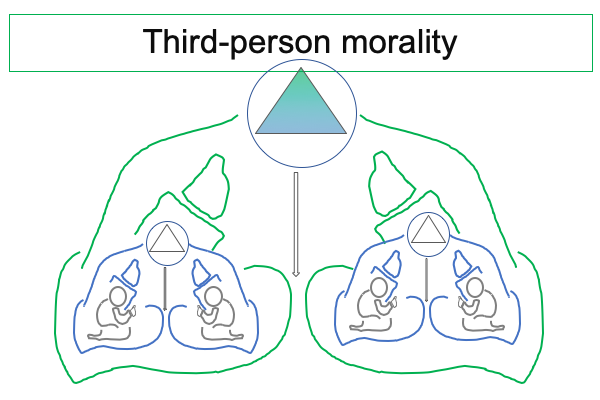

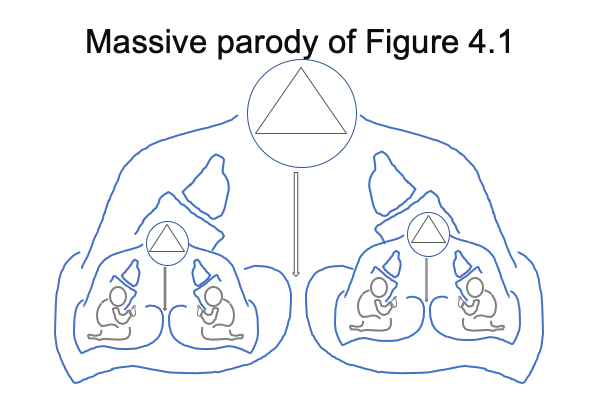

May I now present a massive parody of Figure 4.1?

Each triangle represents a team.

The third person is the team of teams.