Thoughts on Whatever Became of Sin? By Karl Menninger MD (1973) 8E

At this point, we may envision an alternative to the entire nested form of group-think or thinkgroup, sin, and lack of conscience or consciencelacking.

That is thinkgroup(sin(consciencelacking)).

Menninger imagined that the clerics of post-modernism could capture the parallel alternate: thinkdivine(virtue(consciencefree)).

Thoughts on Whatever Became of Sin? By Karl Menninger MD (1973) 8C

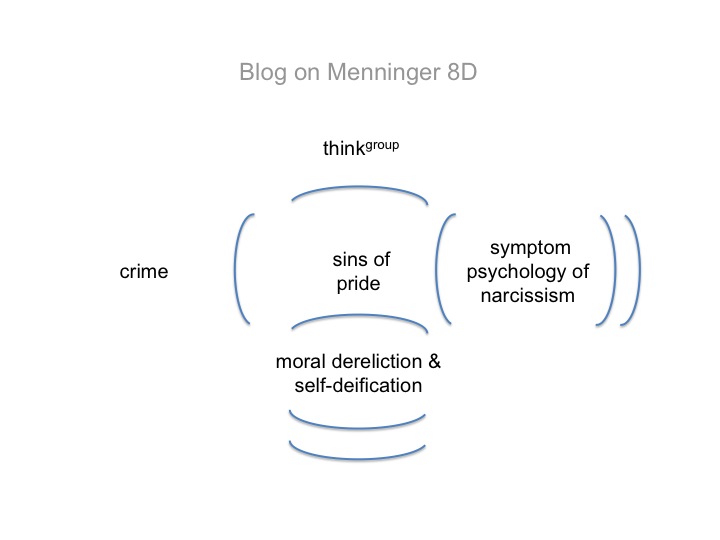

In Chapters 7 and 8, Menninger argued this: A “sin” may also be regarded as a “crime” or a “symptom”, but that does not mean that “sin” is no longer important.

The nested form, crime(sin(symptom)) preserves this substance and adds another layer of sophistication. Every “sin” is contextualized as “crime” and made possible by “symptoms”.

If narcissism is defined as “what makes sins of pride possible”, then the basic nested form of crime(sin(symptom)) becomes crime(sins of pride(narcissism)).

So far so good, now let us go to the other axis.

Menninger mentions both “moral dereliction” and “self-deification” (137) as possible labels for what makes “the sins of pride” possible along this axis. Thus making the nested form “groupthink(sins of pride(self-deification))”.

“Moral dereliction” and “self-deification” belong to “lack of conscience”.

Thoughts on Whatever Became of Sin? By Karl Menninger MD (1973) 8B1

The first section is “sin manifested as pride”.

After listing various manifestations of pride, Menninger raised the issue of narcissism.

Narcissism is a “clinical term”, defined as “a disability that could respond to medical mending”. But this does not preclude the view that narcissism is moral dereliction; that is, a “sin”.

Menninger’s conclusion: Character correction should not belong to the private domain of any single professional discipline (137).

Consider this claim in terms of nestedness. Sin belongs to the realm of actuality. We have seen from previous blogs that “the possibility that underlies sin” is “symptom” (which would correspond to a clinical axis) and (from chapter 7) and “lack of conscience” (which would correspond to the group-think axis) – or perhaps – “free will” (which would correspond to a virtuous axis that seems to be an alternative to the group-think axis).

Now, apply this to the “sins of pride”. “Narcissism” belongs to the “symptom”. The two attitudes of “moral dereliction” (137) and “personal self-deification” (137) belong to the alternatives of “lack of conscience” and perhaps, “free will”.

OK. How about “free conscience”?

Thoughts on Whatever Became of Sin? By Karl Menninger MD (1973) 8B

Chapter 8 is titled “The Old Seven Deadly Sins (and Some New Ones)”.

Here, Menninger explored the individual characteristics that make “acts that lack conscience” possible.

He started by listing the classic seven deadly “sins”, which are not really “sins” but “types of vices”. Then he elaborated on them, offering sets of alternatives, nuances, and synonyms.

The body of the chapter consists of sections devoted to each set of vices.

Thoughts on Whatever Became of Sin? By Karl Menninger MD (1973) 8A

Before going on to Chapter 8, let me revisit the blog 7A through 7F.

At the start of Chapter 7, Menninger turned from the axis of crime(sin(symptom)) to a new axis, tentatively labeled “collective irresponsibility(sin(the seven deadly “vices” (Chapter 8))”.

By the end of Chapter 7, we have a new label for this nested form: group-think(sin(loss of conscience))

Thoughts on Whatever Became of Sin? By Karl Menninger MD (1973) 7E

Now, back to the question lingering from Chapter 7: Why would individuals want to commit wrongs (as part of a group) that they never would have committed as individuals?

Answer: These individuals would have committed the wrongs on their own – if they lacked (what a Christian would call) “conscience”.

Another way to say this is: “lack of conscience” makes sin possible.

We can put that into a new nested form: collective irresponsibility(sin(lacking conscience)).

Collective irresponsibility (or group-think) puts “acts that lack conscience” into context.

Thoughts on Whatever Became of Sin? By Karl Menninger MD (1973) 7D

Who gets the blame for collective irresponsibility (124-127)?

Here is a good option: a scapegoat.

Menninger preferred to blame the group leaders. You know, “the golden calves”.

Not to fault Rene Girard on this, but focusing on the “scapegoat” ignores another feature of group-think: “golden-calfing”.

The golden calf is the person who is invested with all the invincibility associated with the collective. This person cannot be questioned. Everything she – I mean, he – does is correct, no matter how stupid or dysfunctional or short sighted or … without a conscience. No doubt, the golden calf of the Exodus served a similar function. That golden calf could do no wrong until … oh hell, is that Moses?

If you look at the Passion of Jesus the Messiah, you can see that He played the role of the scapegoat. As Girard pointed out, there is significance to that.

At the same time, a host of figures were cast as the golden calves, the Pharisees, the Sadducees, Pontius Pilate, Herod, and best of all, Barabbas. There is significance to that as well.

The scapegoat gets the blame for the collective irresponsibility that is personified by the golden calf.