Looking at Abir Igamberdiev’s Chapter (2024) “Evolutionary Growth of Meanings…” (Part 2 of 4)

0444 Still, the writing of Abir Igamberdiev stands before me.

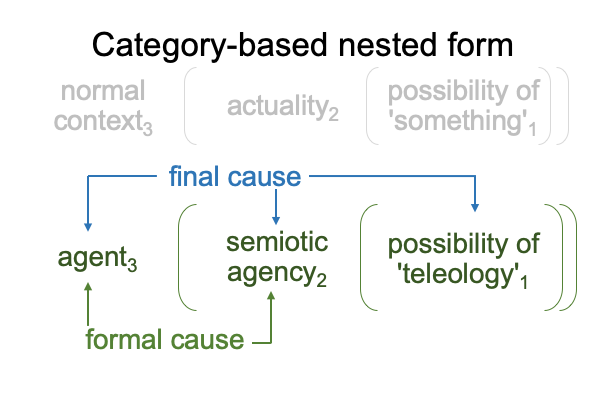

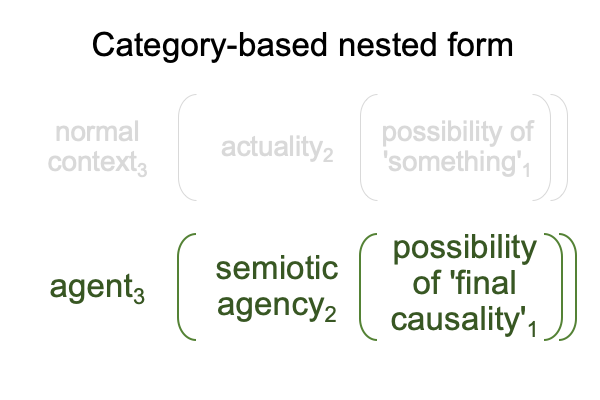

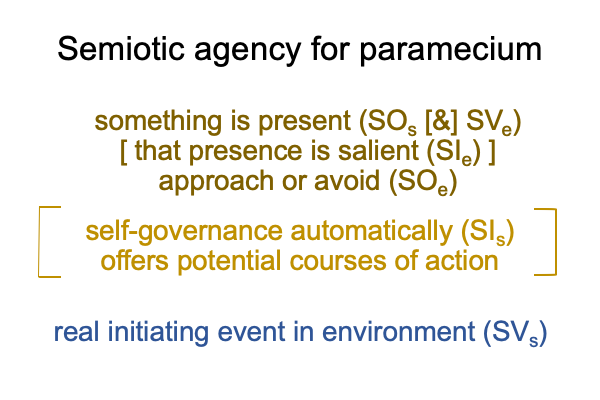

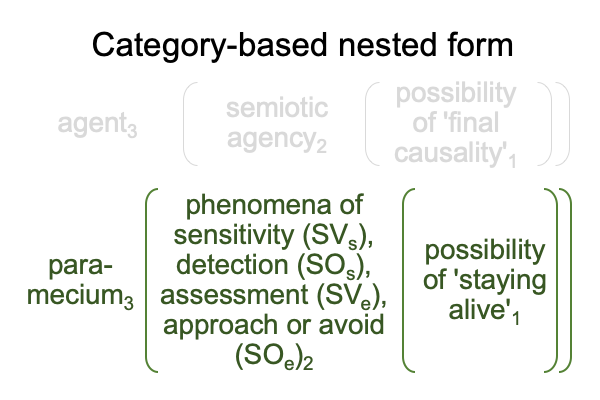

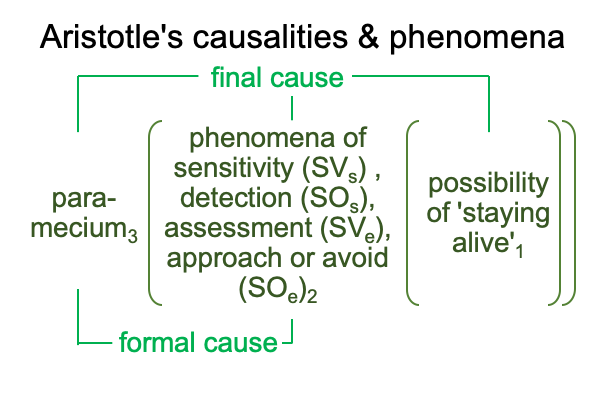

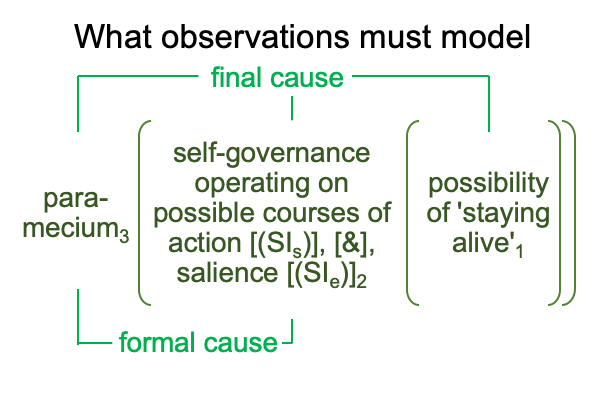

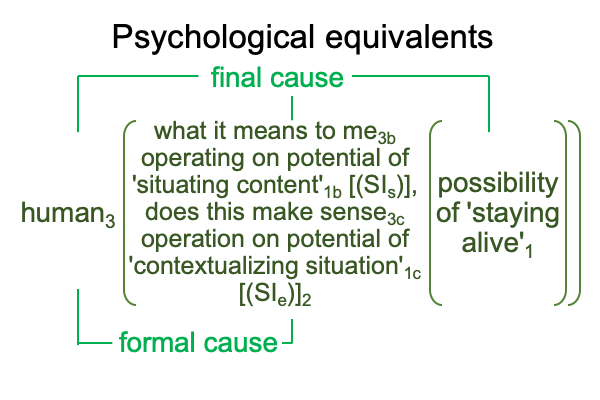

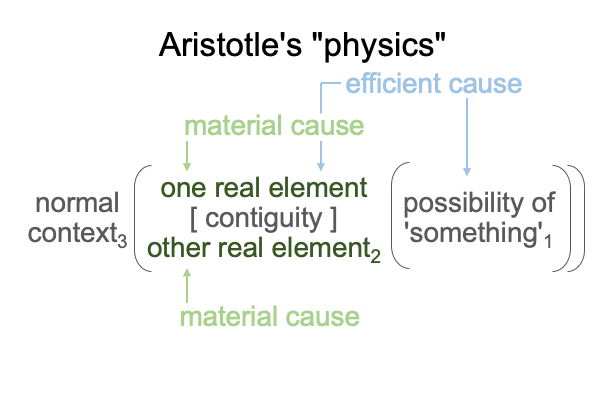

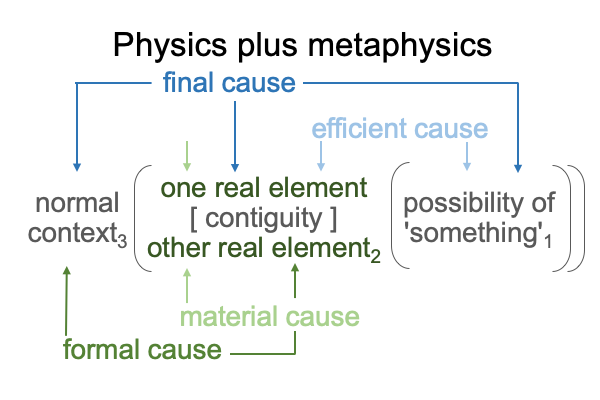

So, let me run through how Aristotle’s four causes play out in the category-based nested form.

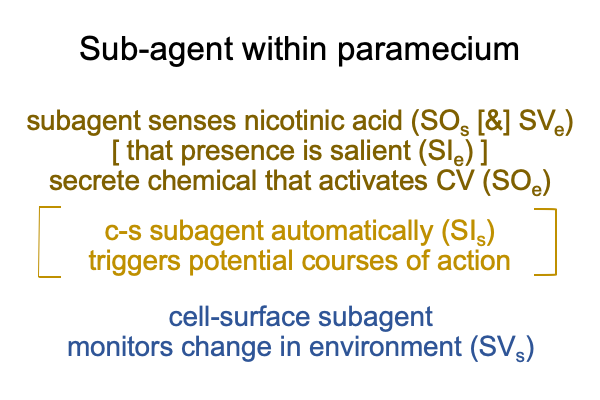

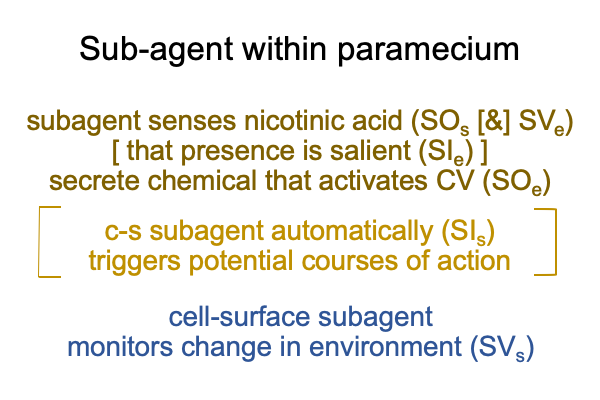

I start with material and efficient causalities.

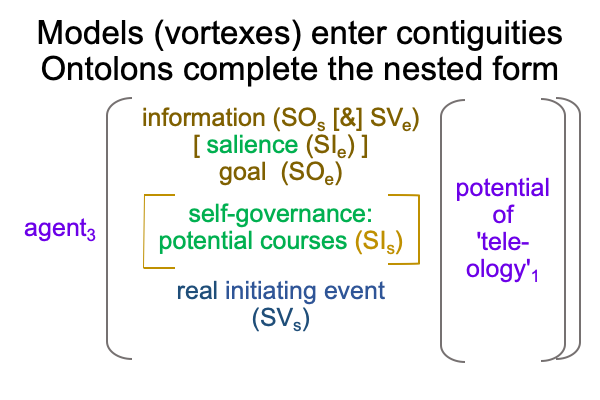

0445 Material causes point to the contiguity between the two real elements. If the elements are matter and form (as in Aristotle’s exemplar), then the material cause introduces some sort of contiguity between the two. For example, molten bronze flows into a plaster hollow (created by covering a wax figure with plaster then melting the wax). For Peirce, the contiguity expresses the character of scientific cause and effect. An observable cause [produces] a measurable effect. For chemistry, reagents [react and turn into] products. Chemical notation is iconic in this regard.

0446 Efficient causes point to actuality2 emerging from (and situating) possibility1.

For example, in chemistry, spontaneous chemical reactions release free energy (heat and entropy). A change in thermodynamic potential supports spontaneous chemical reactions. With a special apparatus, one can measure the heat produced by a chemical reaction by recording the temperature increase of a water bath. Efficient and instrumental causes support observations and measurements that contribute to scientific modeling of the contiguity between reagents and products.

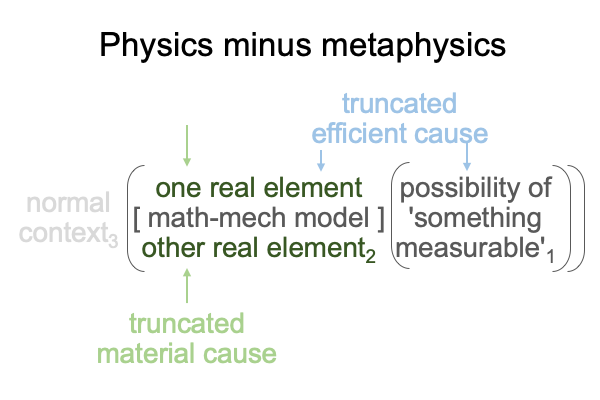

0447 Material and instrumental causes are familiar to scientists. They fall under the label, “physics”.

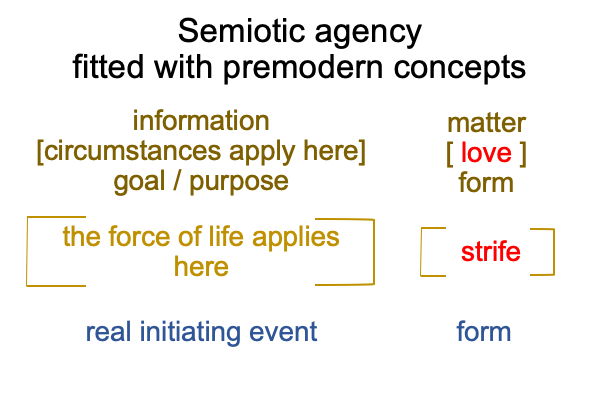

The other two causes are ignored and disparaged by scientists. They fall under the label, “metaphysics”. Metaphysics introduces the normal context and potential as “causes”.

0448 Formal causes concern the ways that a normal context3 contextualizes its actuality2. Typically, formal causes are confounded with material causes. If material causes do not satisfy a formal requirement, then the actuality2 may fail. Indeed, when one thinks about it, the only material causes that are relevant tend to be those that are entangled with formal causes.

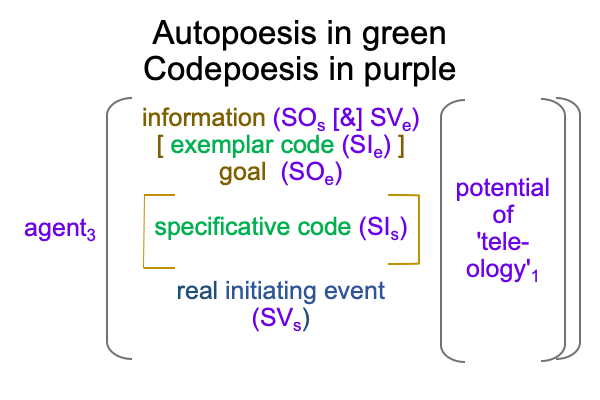

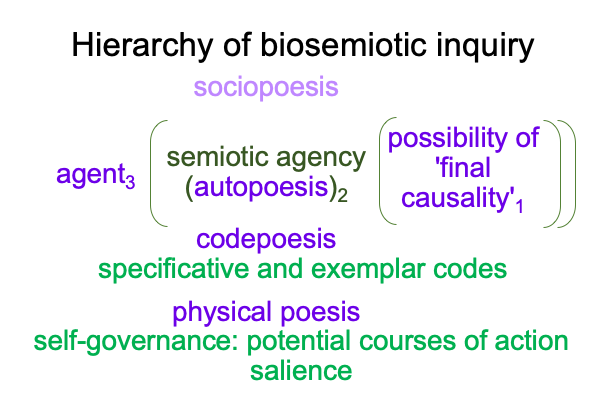

Final causes concern the potential underlying the coherence of the entire category-based nested form. The firstness that supports efficient causes is instrumental. Instrumental of what? Oh, instrumental of efficacy. Okay, there must be another potential, a more substantial potential, that explains why efficient causes are instrumental. Thirdness brings secondness into relation with thirdness. Firstness potentiates the operations of thirdness. Final causes are often framed in terms of “intentionality” and “purpose”.

0449 Surely, all four of Aristotle’s causes are in play when one encounters a thing or event.

Understanding teases out all four causes.

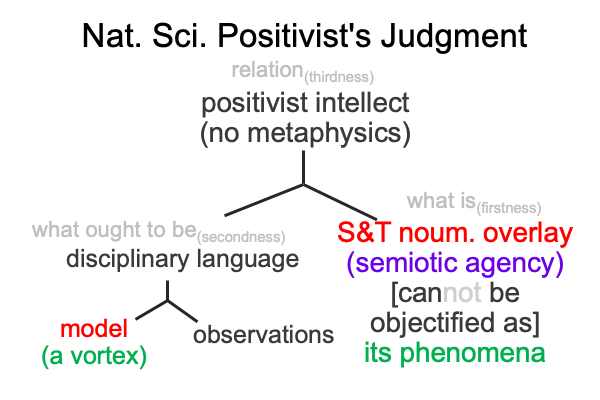

Scientific inquiry does not seek understanding.

Science seeks the truth to be found in models of observations and measurements of phenomena.

Scientific inquiry seeks utility and control.

Of what?

The noumenon or the model?

0450 Scientific inquiry starts with the inorganic world, where the normal context is not apparent. Seventeenth century mechanical philosophers want to reduce inanimate things to mechanistic models. This can only be done by using material causes shorn of formal causes and efficient causes shorn of final causes to build mathematical and mechanical models.

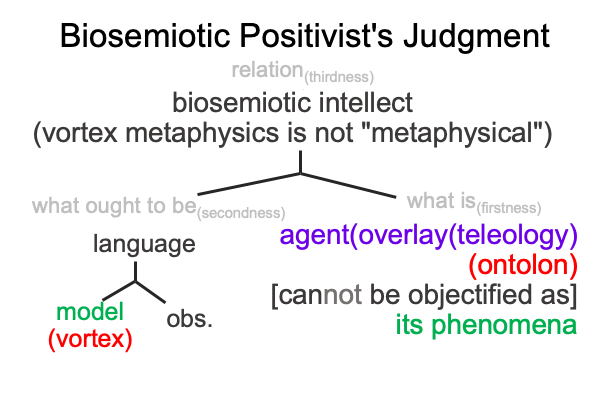

0451 Later, the biologically inclined heirs of the mechanical philosophers strive to reduce animate things to mechanistic models.

Later, the socially inclined heirs of the mechanical philosophers strain to reduce social and psychological things to mechanistic models.

Later, the psychometrically inclined heirs of the mechanical philosophers convert what people are willing to say into data, in order to build opportunities for empirio-normative domination.