Looking at Victoria Alexander’s Chapter (2024) “…The Emergence of Subjective Meaning” (Part 2 of 5)

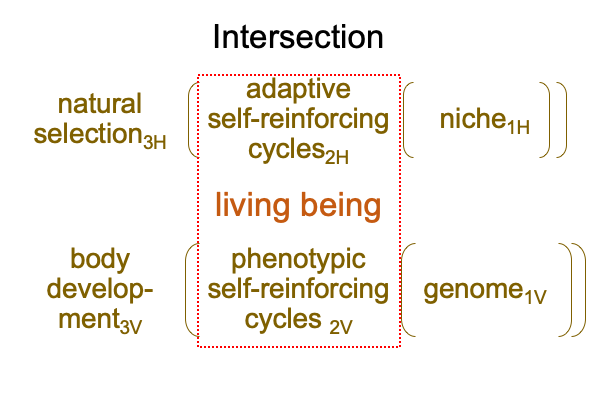

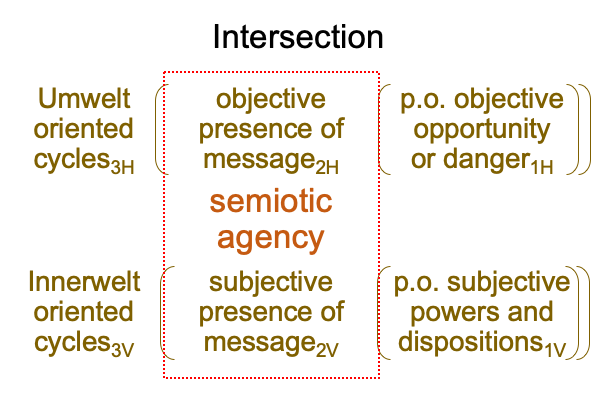

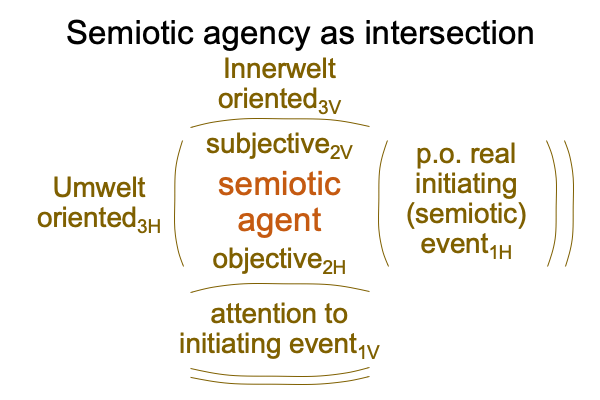

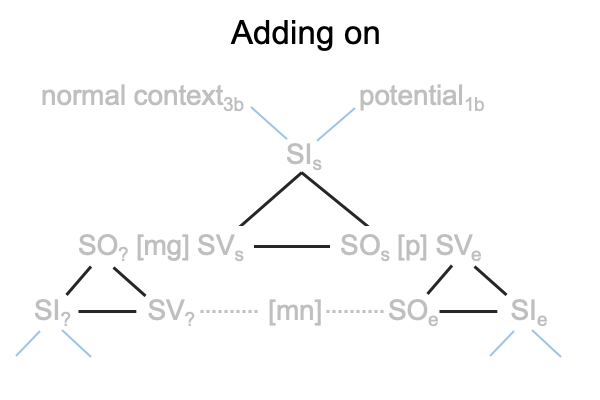

0710 The intersection is a mystery because two actualities constitute one actuality. Two category-based nested forms come together because their actualities apply to the same entity.

That is sort of confusing, especially when the single actuality2 has yet to be framed with a normal context3 and potential1.

0711 Let me consider each actuality2 on it own.

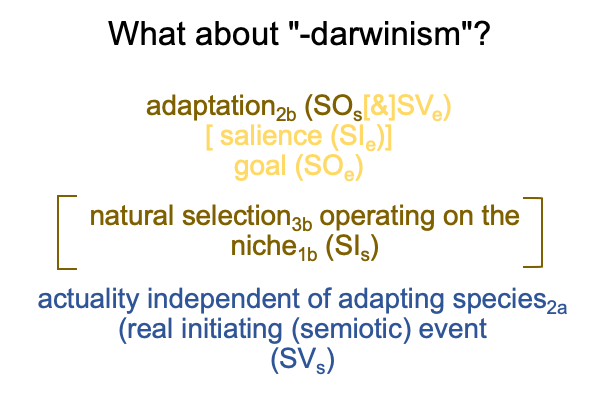

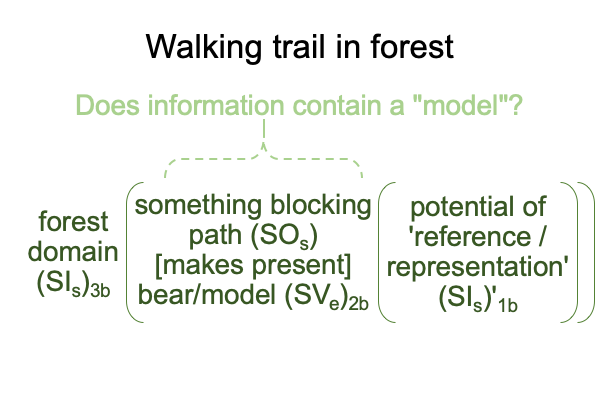

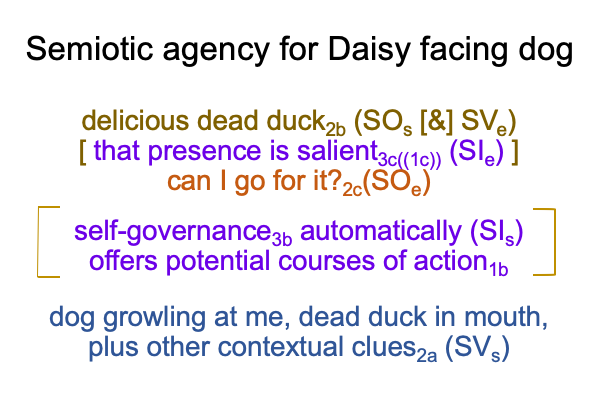

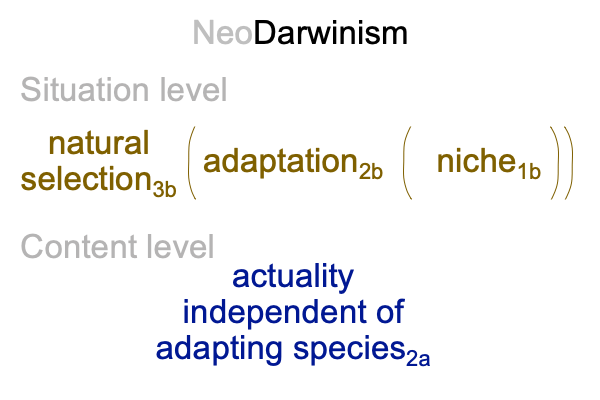

The first actuality is adaptation2. Adaptation2 corresponds to the “darwinism” of “neodarwinism”. The normal context of natural selection3b brings the actuality of an adaptation2b into relation with an organism’s niche1b. The subscript, “b”, denotes the situation level. So, there must be a content-level actuality2a (at a minimum). The niche1b serves as the potential of that content-level actuality2a.

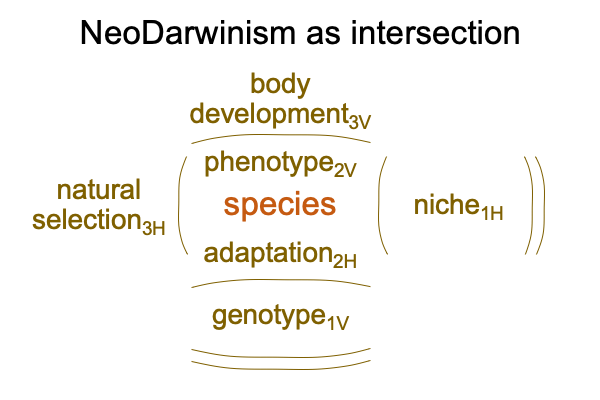

0712 Here is a picture.

0713 Yes, a niche1b is the potential1b of an actuality independent of the adapting species2a.

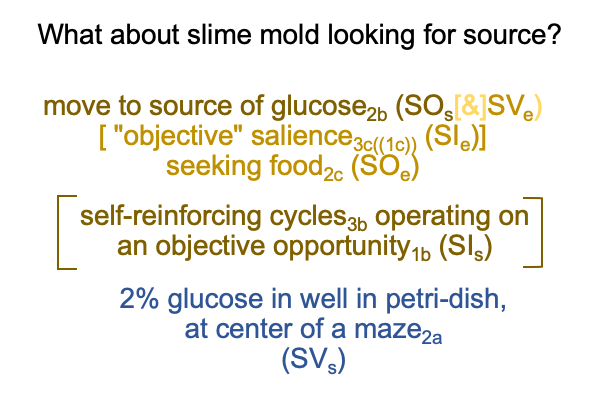

This formula applies to all sorts of “niches” fashioned within the boutiques of academic biology.

For example, “niche construction” fits the formula. Beavers build a dam on a fast moving stream and the stream becomes a glen that provides plenty of food for the beavers. The dam serves as a home. Surely, when one dams a fast moving stream, the result is a glen that beavers can flourish in. So, the term “niche construction” points to the fact that the actuality independent of the adapting species2a may be a process. Plus, “niche construction” does not not stop there. “Niche construction” indicates that the actuality independent of the adapting species2a may be purely relational structures, such as… um… triadic relations.

0714 I shudder to think what type of genus would adapt into a niche containing the potential of triadic relations.

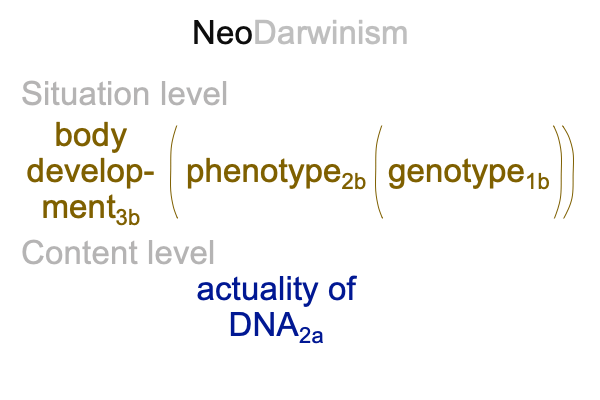

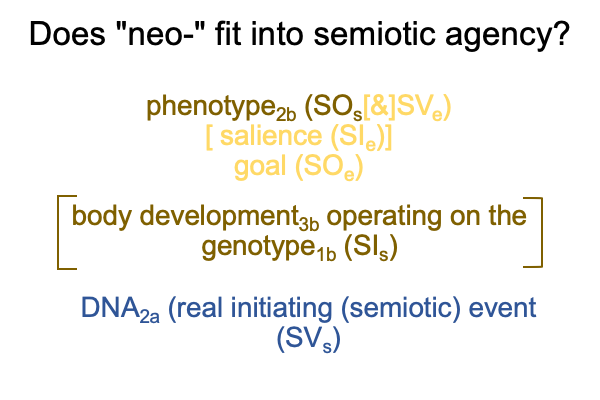

0715 The second actuality is phenotype2. Phenotype2 corresponds to the “neo” of “neodarwinism”. The normal context of body development3b brings the actuality of a phenotype2b into relation with the organism’s genotype1b. Or maybe, I should use the word, “genome1b“. I guess the words are both different and the same. The subscript, “b”, denotes the situation level. DNA2a is the content-level actuality.

0716 Ah, the genotype1b is the potential1b of DNA2a.

0717 What else is curious about the two-level interscope for phenotype2b?

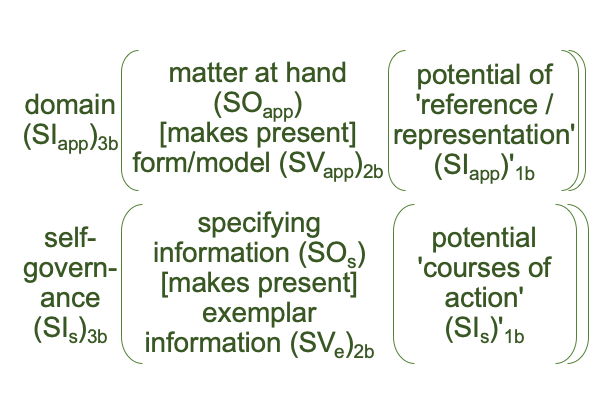

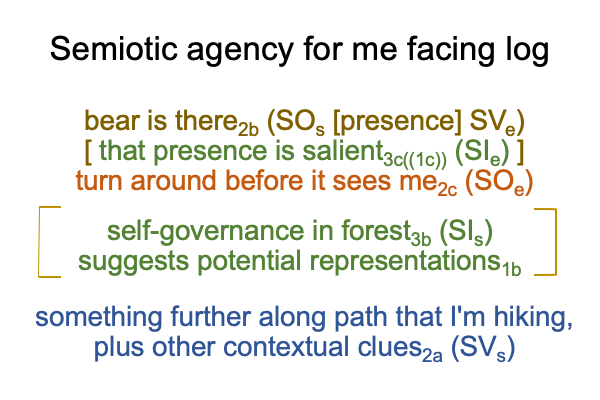

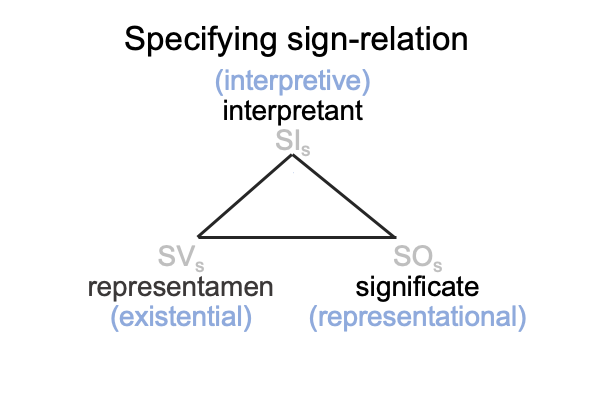

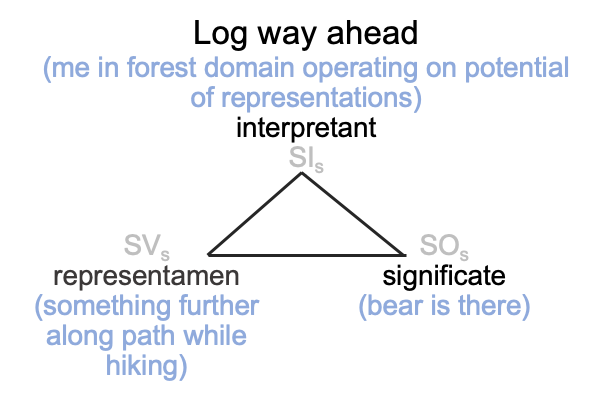

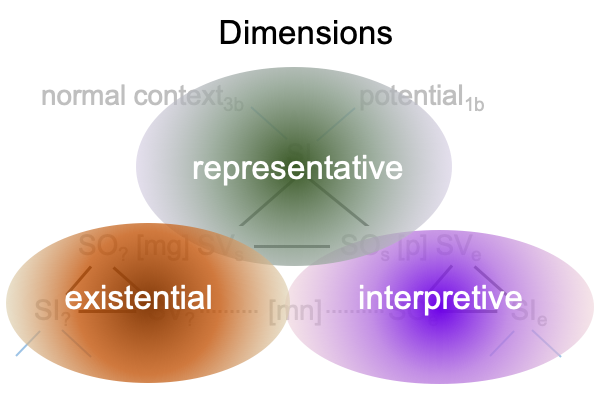

0718 The situation and content levels constellate a specifying sign-relation. DNA2a (SVs) stands for the phenotype2b(SOs) in regards to body development3b operating on the variety of ways that DNA can be translated into proteins (the genotype1b) (SIs).

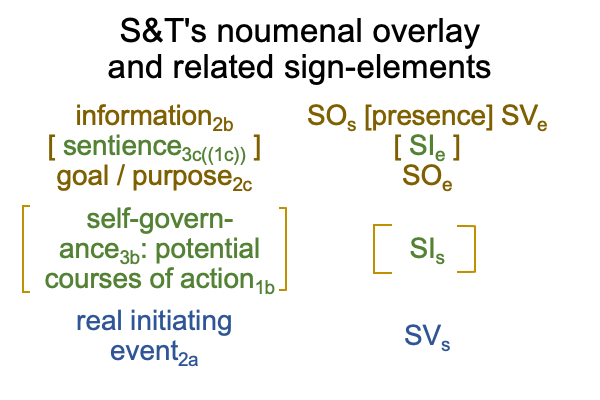

If this is the case, then I wonder, “Does this specifying sign-relation fit into Sharov and Tonnessen’s noumenal overlay?”

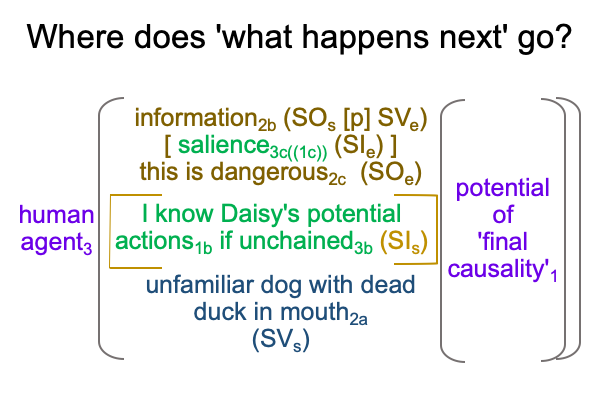

The answer is, “Yes, here is a picture.”

0719 Isn’t that curious?

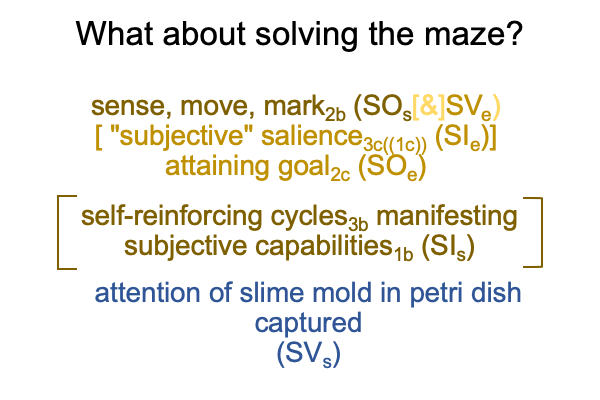

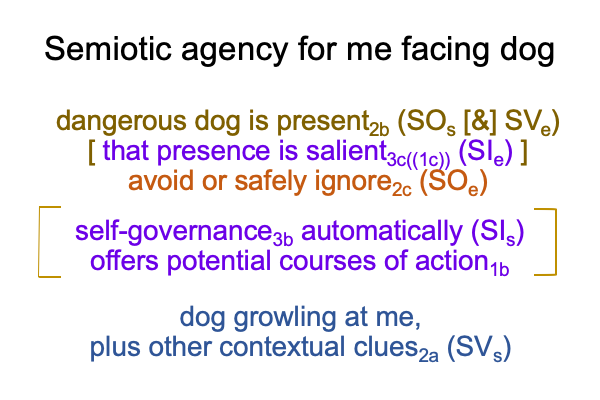

The specifying sign-object (SOs) of phenotype2b does not take the inquirer to the biosemiotic fullness of semiotic agency. The exemplar sign-relation remains occluded. Remember that the exemplar sign-relation associates with emergence (points 0280 through 0292). It also associates with a goal2c that a biosemiotician recognizes as meaning2c.

0720 What does the biosemiotician recognize with respect to the “neo” component of neodarwinism?

The biosemiotician recognizes DNA2a (SVs) as message and phenotype2b (SOs) as presence.

0718 What about the “-darwinism” of “neodarwinism”?

The same principle applies. The situation and content levels constellate a specifying sign relation. The exemplar sign remains occluded. An actuality independent of the adapting species2a (SVs) stands for an adaptation2b (SOs) in regards to natural selection3b operating on an organism’s niche1b (SIs).