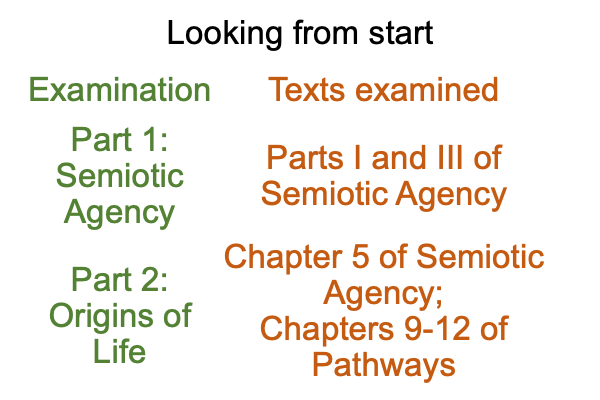

Looking at Alexei Sharov and Morten Tonnessen’s Chapter (2021) “Human Agency” (Part 5 of 5)

1260 Say what?

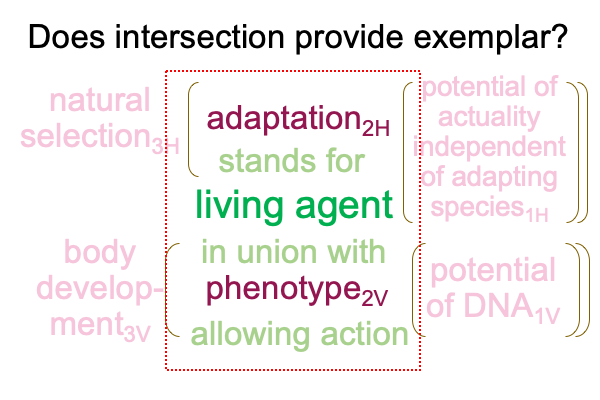

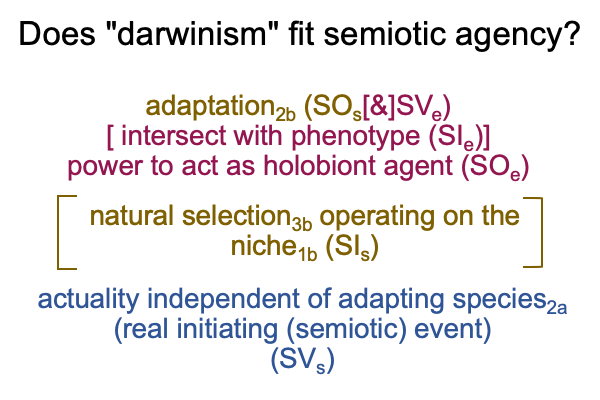

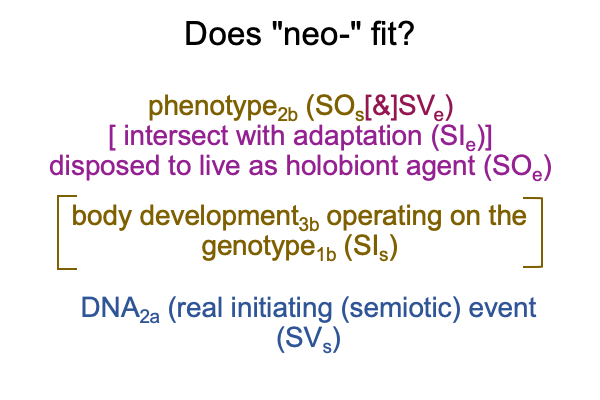

Here is the intersection, once again.

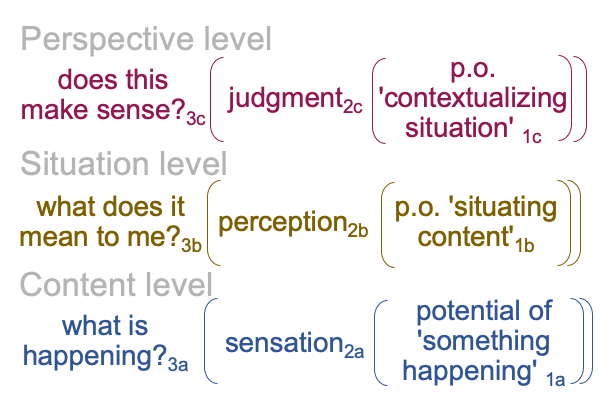

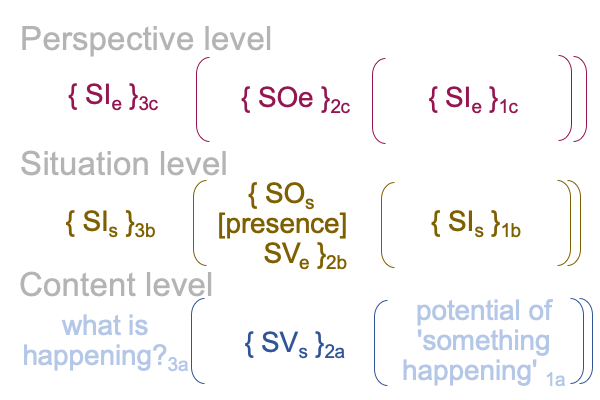

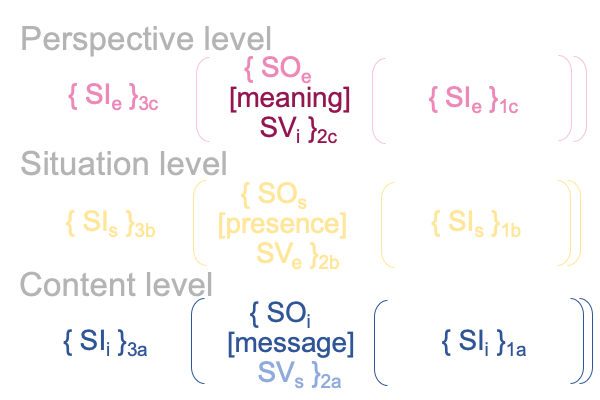

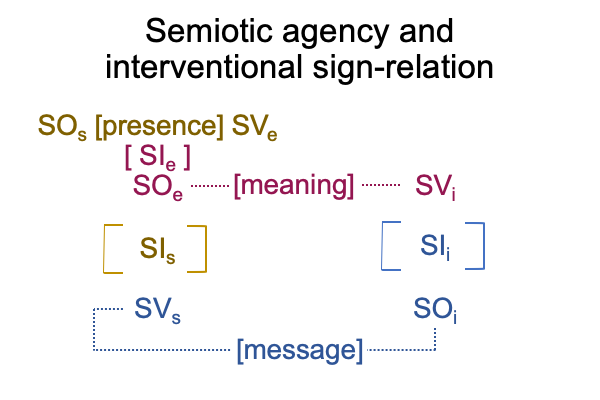

1261 Yes, I can make out a configuration that looks like an exemplar sign-relation.

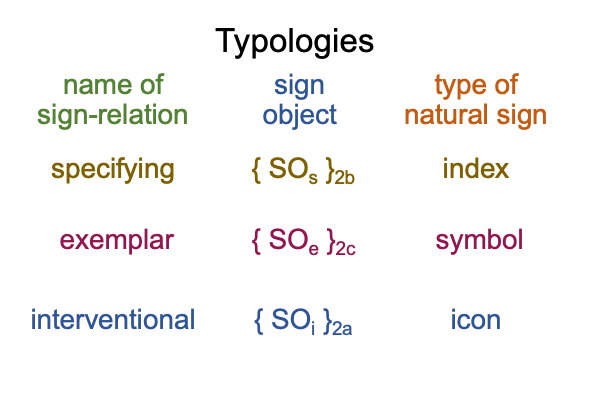

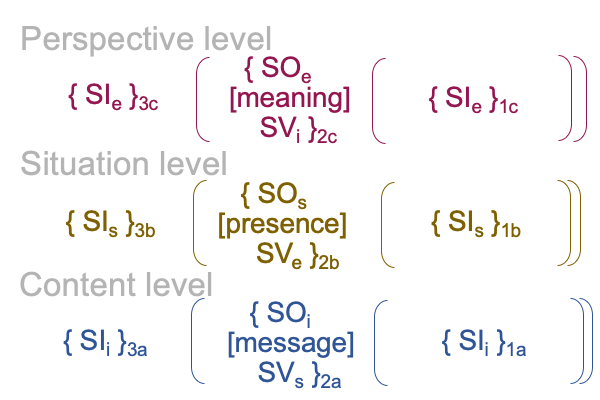

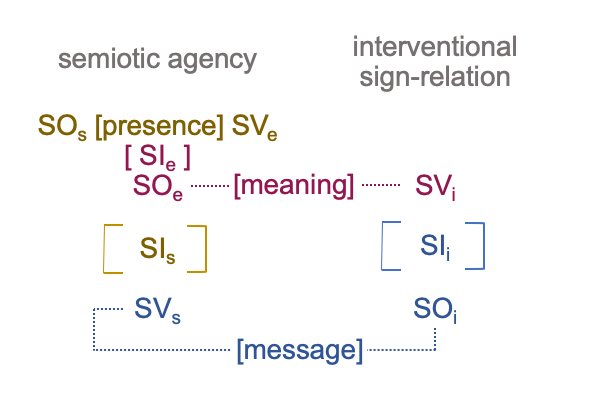

One version of the exemplar relation goes like this. Information2b (SVe) stands for a goal (SOe) in regards to a normal context asking something like, “Does this make sense?”3c operating on the potential of ‘situating information’1c (SIe).

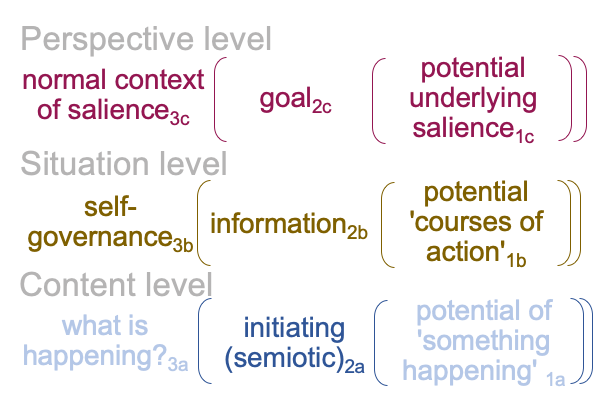

In the above diagram, information2b (SVe) is adaptation2H. The goal2c (SOe) is the power to live as an agent. The [contiguity] (SIe) is an intersection with the phenotype3c operating on the potentials that the phenotype provides1c.

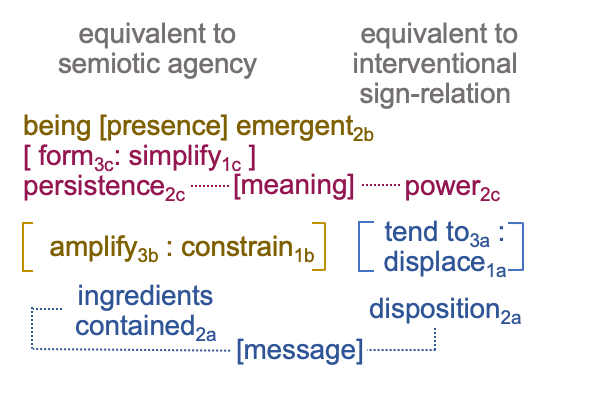

1262 For the -darwinism version of exemplar sign-relation, the two actualities are adaptation2b (SVe) and the power to live as agent2c (SOe). The contiguity is the normal context of an intersection with one’s phenotype3c, operating on the potentials that the phenotypes provide1c (SIe).

1263 For the neo- version of the exemplar sign-relation, the two actualities are phenotype2b (SVe) and the disposition to live as an agent2c (SOe). The contiguity is the normal context of an intersection with one’s adaptations3c, operating on the potentials that adaptations provide1c (SIe).

1264 What do these two exemplar sign-relations tell us?

Adaptations express power?

Adaptations allow survival to the extent that the phenotype allows them?

Phenotypes express dispositions?

Phenotypes are expressed as a suite of adaptations whether the agent needs them or not?

No wonder biologists cannot “define” evolution concisely.

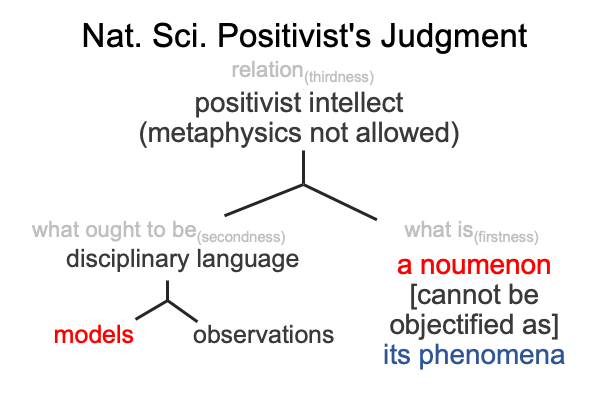

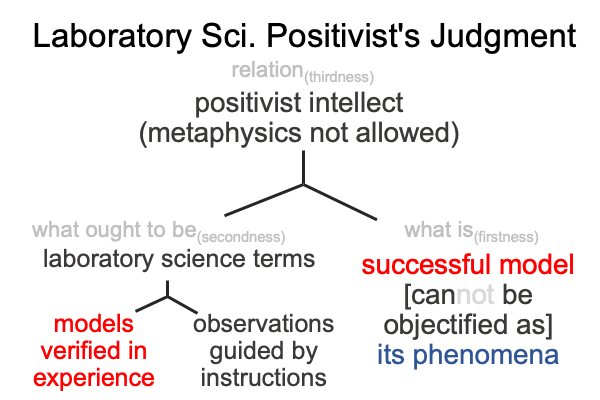

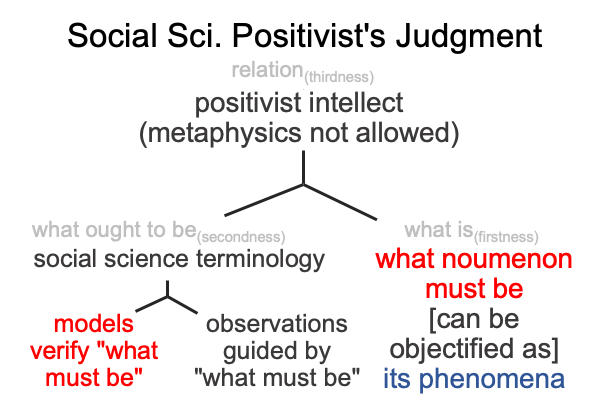

1265 Surely, this argument does not please the positivist intellect of the physicists and the chemists.

Biological evolution is a mystery, the intersection of two independent sciences, natural history and genetics.

But, that is not all. I can delineate an implication for one of the contradictions inherent in biological evolution.

Phenotype is necessary for a -darwinian explanation, where “evolution” operates as an agent. Phenotypic dispositions are inseparable from individual adaptive powers.

1266 Also, adaptation is necessary for a neo- (or genetic) explanation, where “evolution” operates as an agent. Adaptive powers are inseparable from species-specific dispositions.

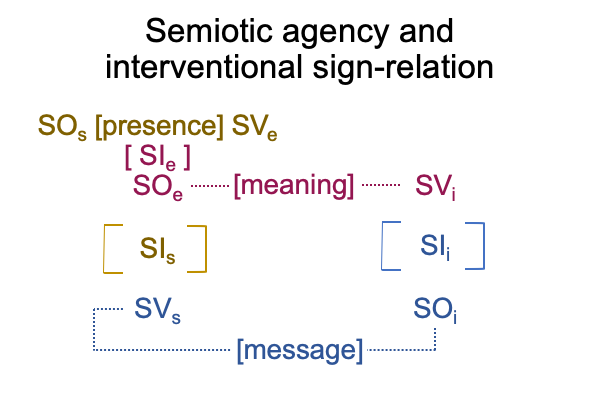

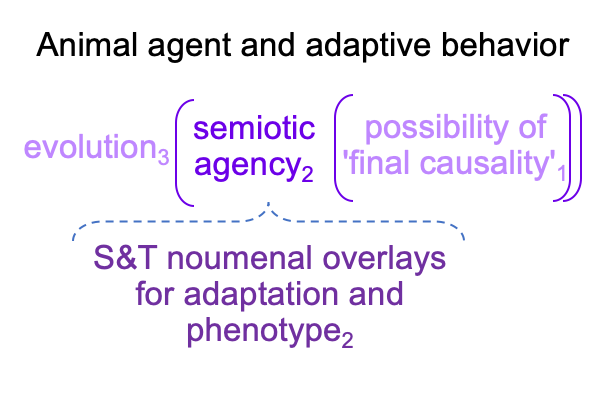

1267 Yes, I am arriving at a contradiction that cannot be resolved into either natural history or genetics. Both of these discipline’s semiotic agency have the same agent, “evolution”. But, what is the ‘final causality’?

1268 Here, the logics of firstness come into play. The logics of firstness are inclusive and allow contradictions. Evolution as an agent3 brings the actualities of adaptation and phenotype as semiotic agencies2 into relation with ‘a creative potential that evolutionary scientists regard as real’1. But, it is unreal, because it represents a ‘final causality’ that stands beyond anything than the human can imagine.

After all, humans are evolved living beings. What are we imaging when we try to picture this ‘final causality’?

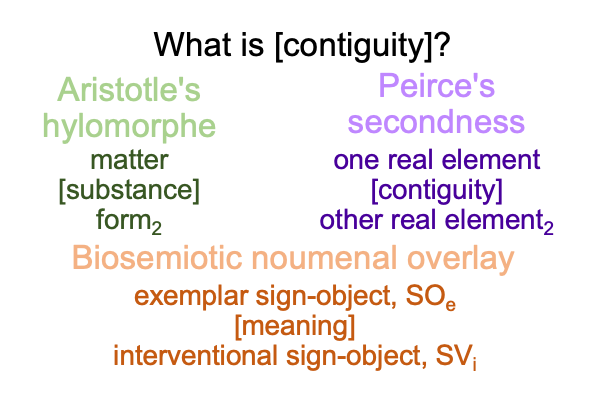

1269 Modern evolutionary biologists may attribute the reality of the creative potential underlying evolution as an agent to matter alone, rather than matter [substance] form.

Postmodern biosemioticians may attribute the reality of the creative potential to triadic relations, such as the triadic relations reified into the matter [substance] form of semiotic agency.

1270 What does this imply?

The attribution of the biosemiotician encompasses the attribution of modern evolutionary biology.

The answer approaches the metaphysical in precisely the way that the Aristotle-tolerating positivist intellect currently uses the term, “metaphysics”, for “religious”.

The positivist intellect declares, “Religious empirio-schematic models are not allowed.”

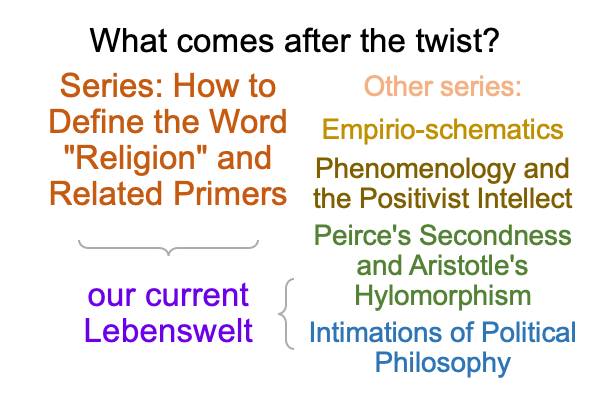

1271 And, this raises a question, “How to define the word “religion?”

This question is the title of one of Razie Mah’s three masterworks.

More on that later.