Looking at Alexander Kravchenko’s chapter (2024) “A Constructivist Approach…” (Part 3 of 6)

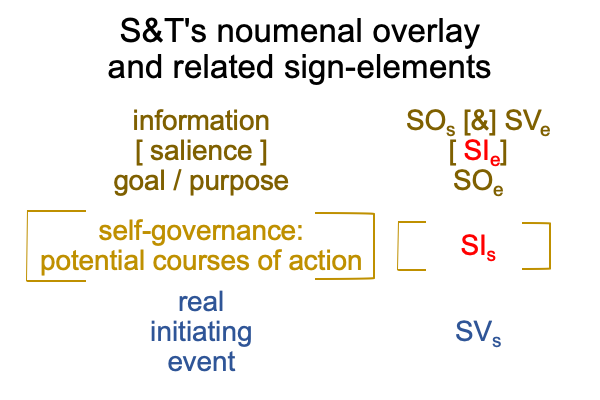

1021 So, in this language game concerning theories of meaning, I end up with the appearance that “end-directive activities” reside “out there” (as the interventional sign-vehicle (SVi) expresses an agent’s goal2c in action) as well as “in here” (as the goal2c itself (SOe)).

1022 Dare I continue?

The author calls the SOe “objective” and the SVi “objective in parentheses”.

In this terminology, the goal2c (SOe) is “objective” and its expression2c (SVi) is “objective in parenthesis” because… well… any intervention can go wrong (so, it is better to put the objective in parenthesis).

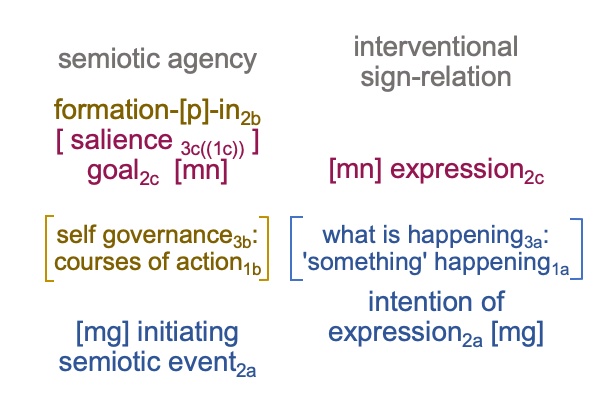

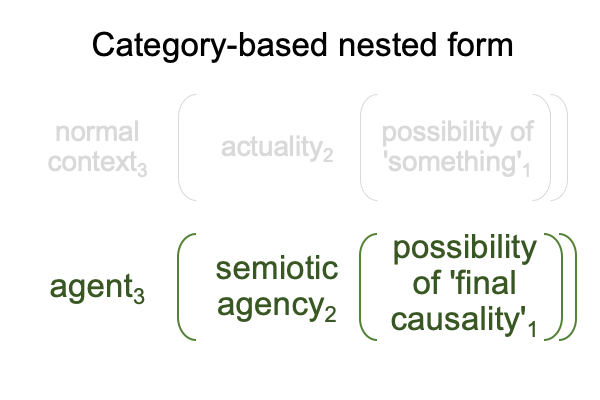

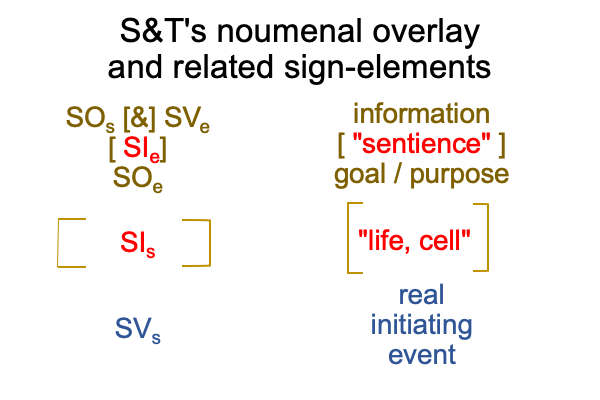

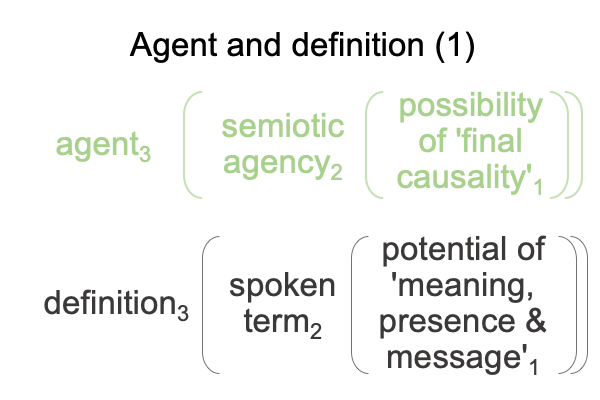

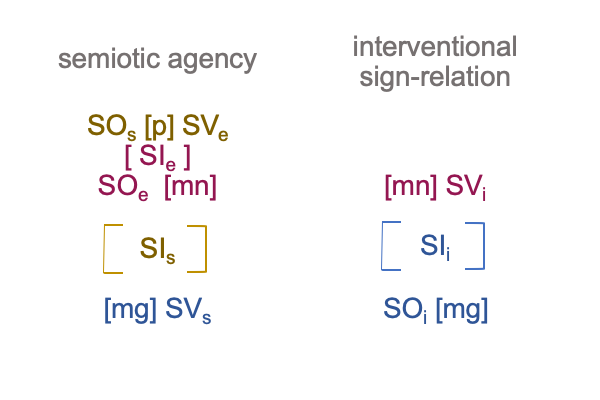

1023 A rewarding feature of this modern nomenclature is that it allows a clean break between semiotic agency (the Innerwelt aspect) and the interventional sign-relation (the Umwelt and Lebenswelt aspect).

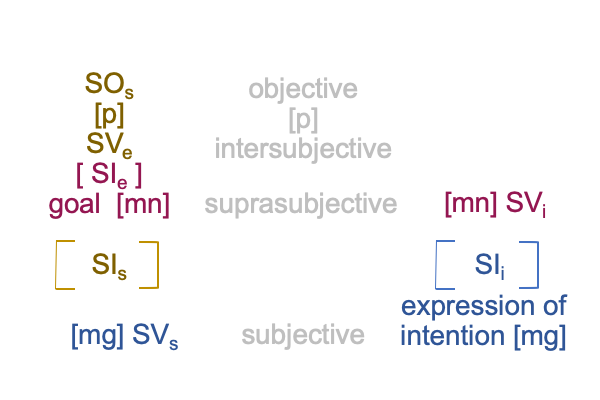

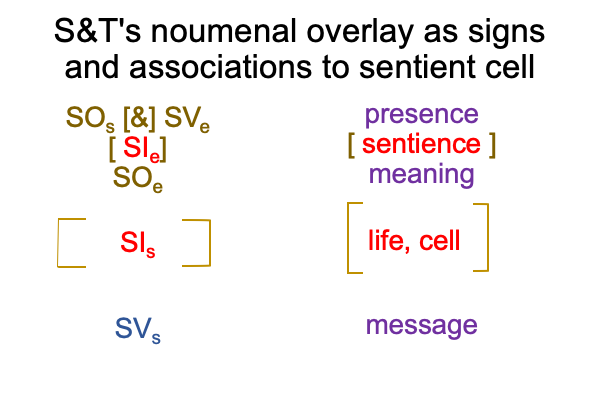

Here is a picture.

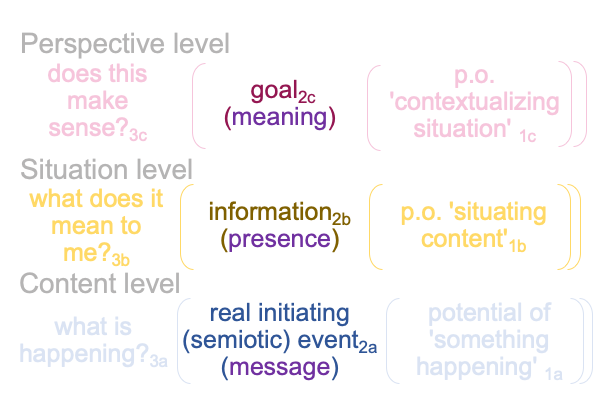

For the contiguities, [p] is [presence], [mn] is [meaning] and [mg] is [message].

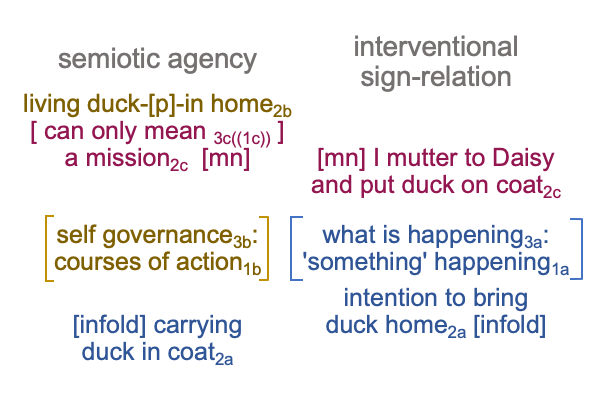

1024 A clean break makes intellectual labors simpler when [message] is [inter] and more complicated when [message] is [infold].

When I speak to myself, I labor as semiotic agency produces a speech-act that serves as an intervention which activates my… um… semiotic agency.

Is the [message] [inter] or [infold]?

Does it have to be one or the other?

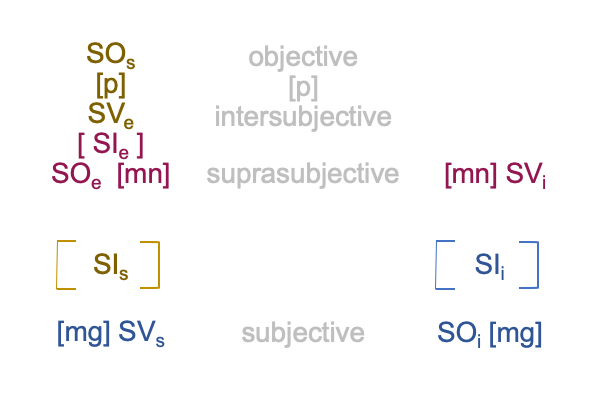

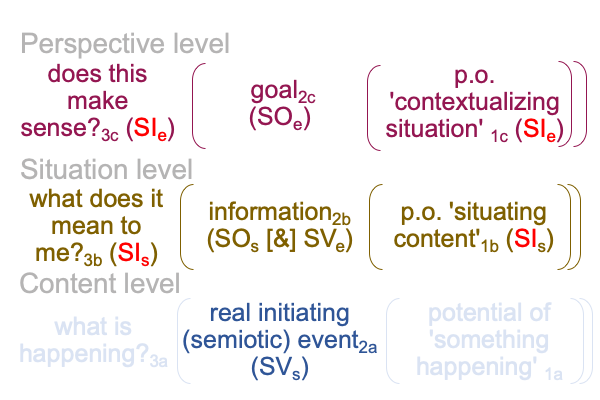

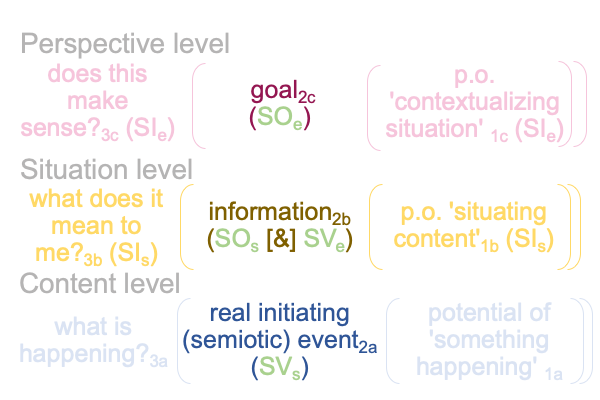

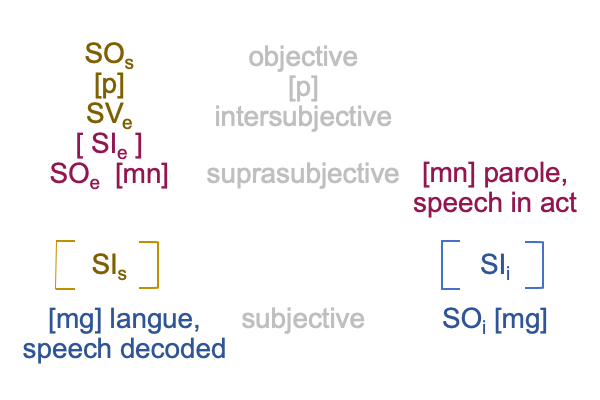

1025 The medieval scholastics come up with terms that are discussed in Looking at John Deely’s Book (2010) “Semiotic Agency” (appearing in Razie Mah’s blog for October, 2023). The terms pertain to the levels of the scholastic interscope for how humans think. The term, “subjective”, labels the content level, where SVs resides. The term, “objective”, labels the situation level, where SOs is located. The term, “intersubjective” labels the situation level, where SVe is located. The term, “suprasubjective”, labels the perspective level, where SOe is located.

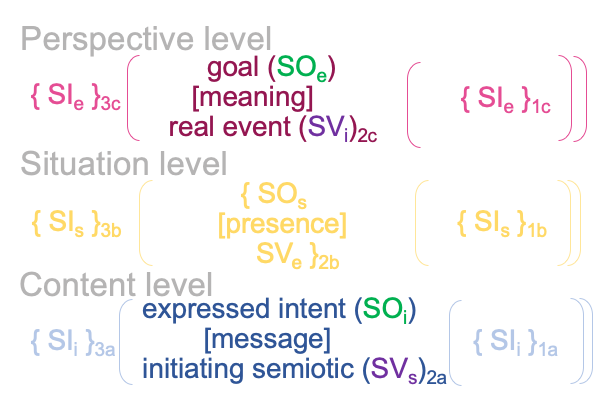

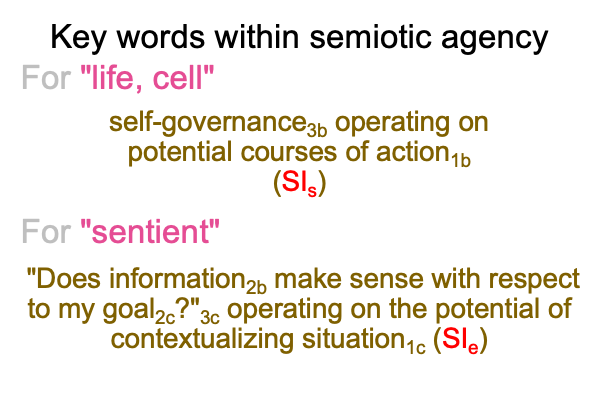

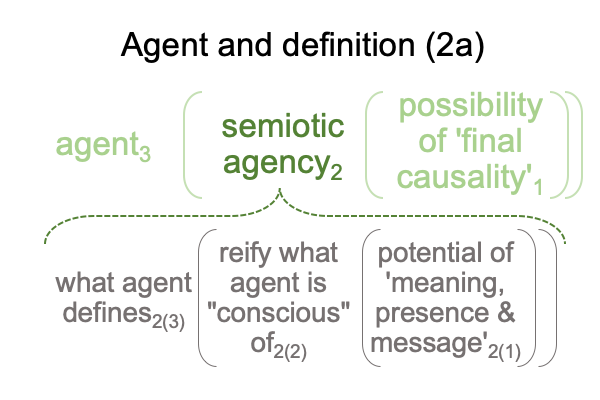

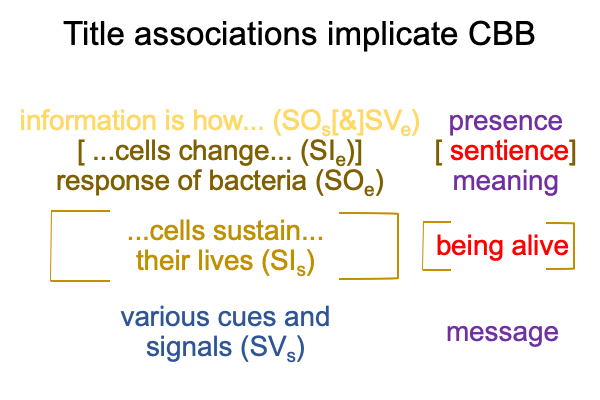

1026 Here is a picture.

1027 This implies that SOe [meaning] SVi is, for scholastics, “suprasubjective’ (that is, “subjective from a divine perspective”) and, for modern academics, the locus of both “objective” and “objective in parenthesis”.

In short, the biosemiotic structure of suprasubjectivity contains both objective goal2c (SOe) and its (objective) expression in the moment (SVi).

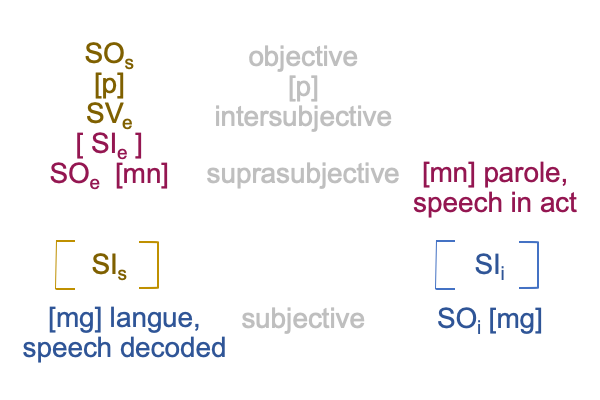

1027 As if to demonstrate the delicacy of this modern distinction, the author offers the example of spoken language as the arbitrary relation between two systems of differences, parole (speech in act) and langue (speech decoded).

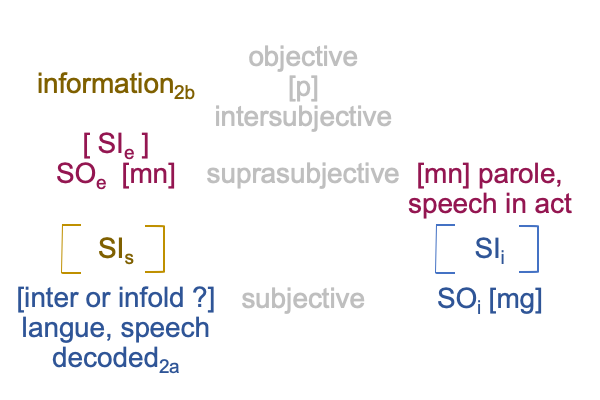

1028 Can the reader guess how these two systems of differences fit into the above diagram?

Here is what I figure.

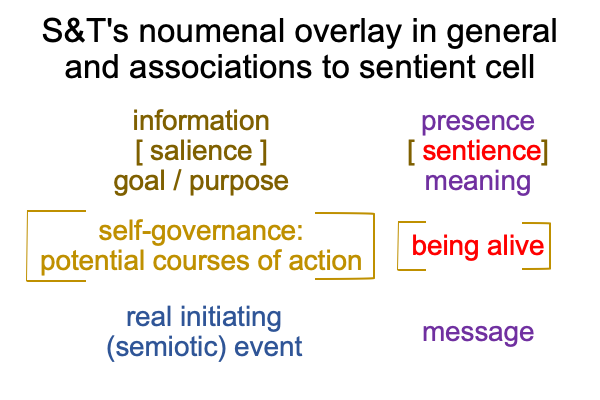

1029 The information2b of semiotic agency is within the agent, even though it2b concerns what2a apparently is located without.

For this reason, I may playfully modify information2b into -formation2b (SOs) [presence] in-2b (SVe)

If the goal2c is to say ‘something’, then SVi is parole, a speech act. The parole (SVi) stands for an intention2a (SOi) in regards to what is happening3a operating on the potential of ‘something’ happening1a (SIi). Of course, this intention2a(SOi) is not the same as the originating goal (SOe) and that becomes evident when spoken words are instantly decoded by a langue operator2a (SVs) as an event akin to sensation2a.

1030 That brings me (the examiner) back to [meaning] as the contiguity between an objective goal2c (SOe) and an (objective) parole (SVi).