Looking at Arthur Reber, Frantisek Baluska and William Miller Jr.’s Chapter (2024) “The Sentient Cell” (Part 2 of 4)

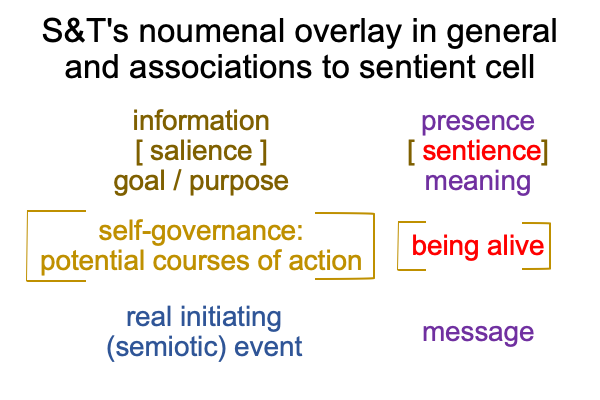

0611 Ah, I see a pattern. The titular terms of “sentience” and “cell” label the same noumenal elements where subagents reside. Plus, these are the elements that need to be modeled. They are not the elements associated to phenomena.

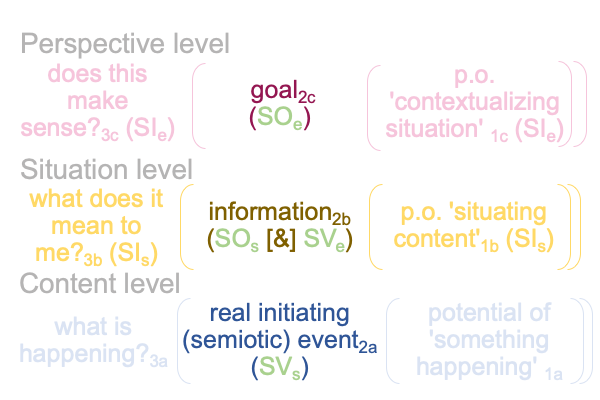

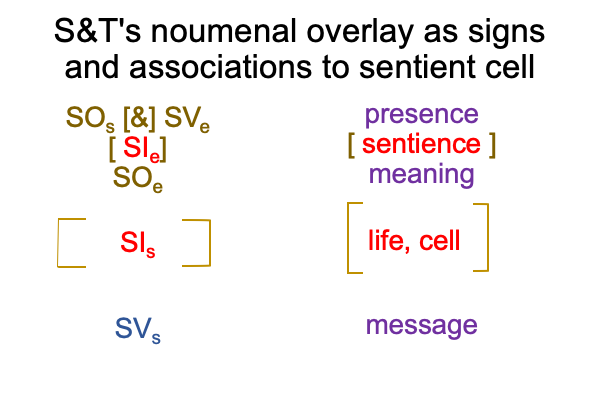

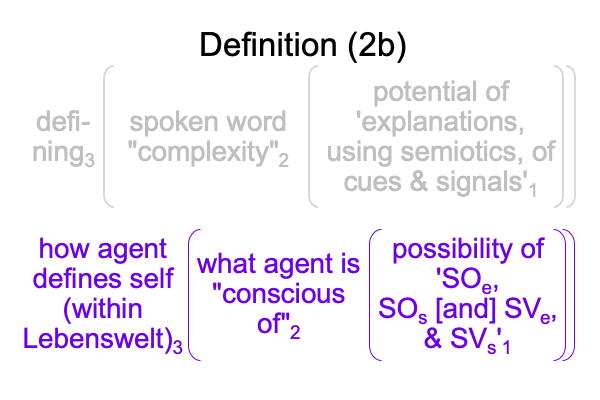

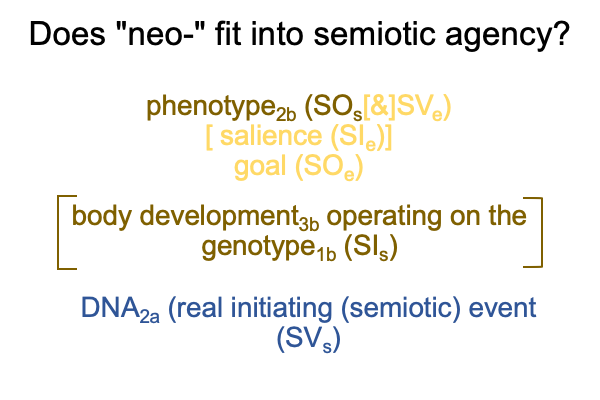

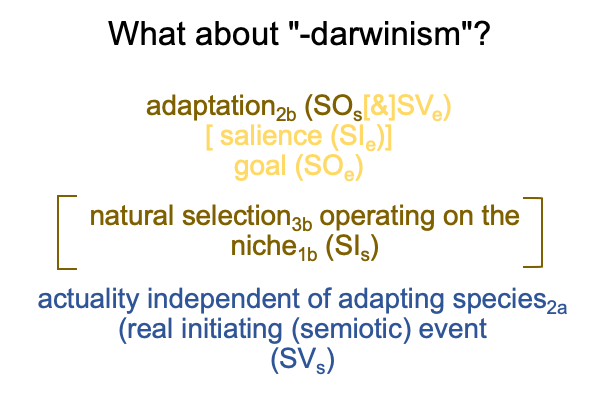

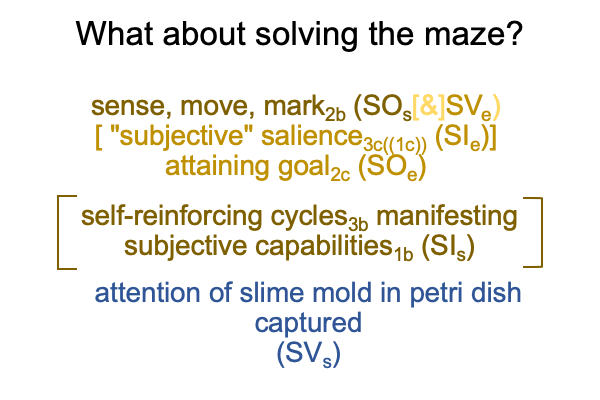

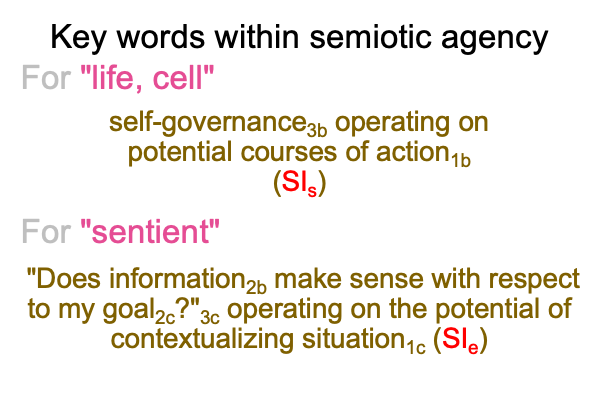

0612 Here are the key words and their respective sign-interpretants.

The specifying sign-interpretant (SIs) derives from Kull’s criteria for semiotic agency (see points 0026 through 0037). Self-governance associates to a situation-level normal context3b and a choice of actions goes with situation-level potentials1b.

The exemplar sign-interpretant (SIe) is may be labeled, “salience3c,1c“, in order to avoid articulating (or explicitly abstracting) the perspective-level normal context3c and potential1c. The descriptions in the preceding figure constitute my rough guesses.

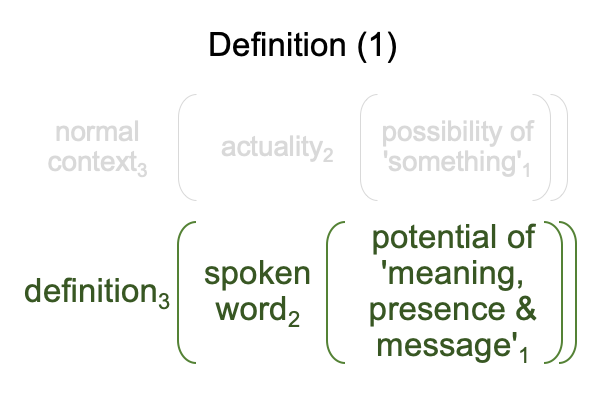

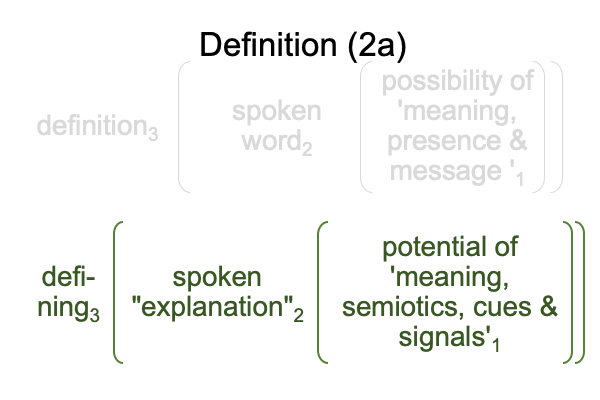

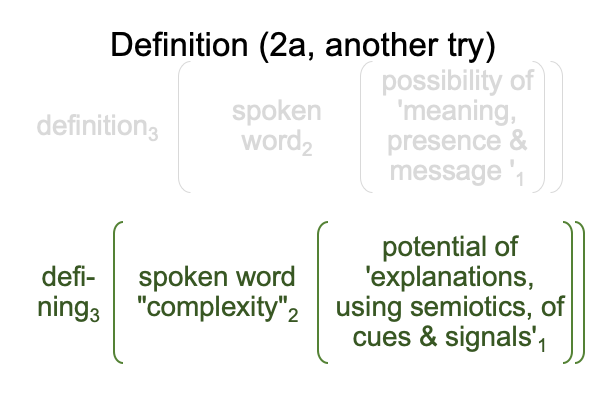

After all, what does the spoken word, “salience”, mean?

Why is it present in this particular instance?

Does this particular word send a message?

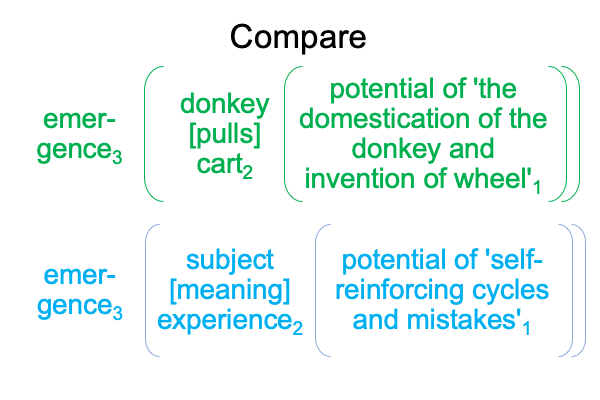

0613 I suppose that I can compare my descriptions of the specifying and the exemplar sign-interpretants to the scholastic interscope for how humans think, appearing in Comments on John Deely’s Book (1994) “New Beginning” (by Razie Mah, available at smashwords and other e-book venues), as well as Looking at John Deely’s Book (2010) “Semiotic Animal” (Razie Mah’s blog for October, 2023).

John Deely (1942-2017) is quite the scholar. His books plumb scholastic literature for insights into postmodern semiotics.

0614 What does he discover in these explorations?

He finds that Charles Peirce (in the 1800s) comes up with the same definition of the sign-relation as Baroque scholastic, John Poinsot (in the 1600s).

Quite a discovery.

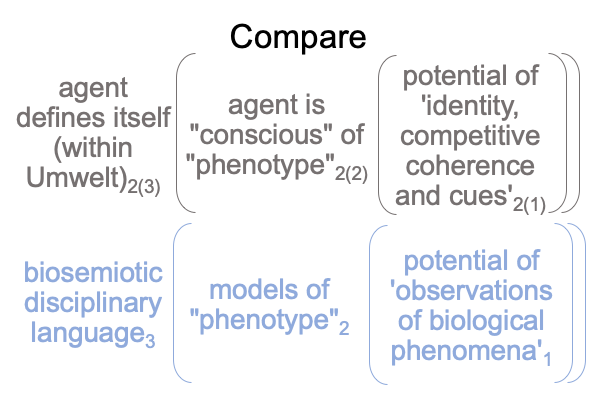

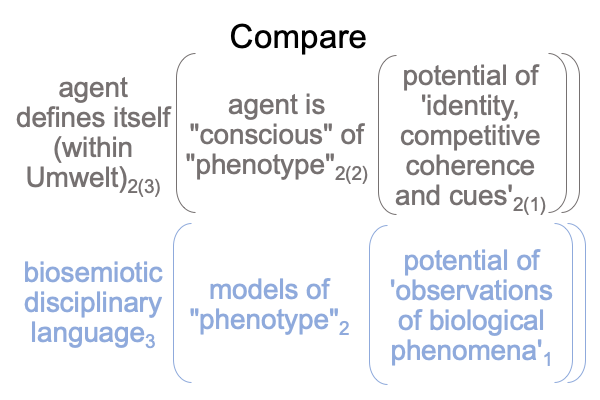

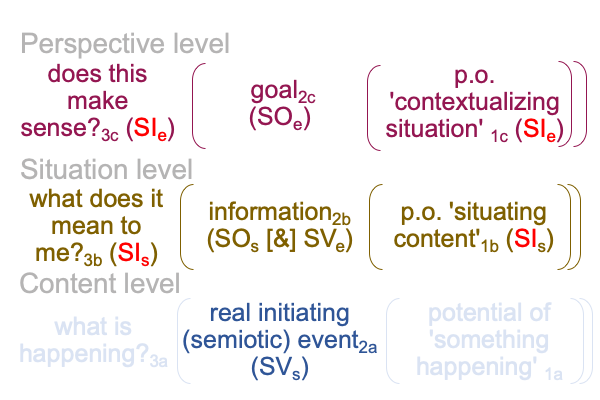

He also sets the stage for Mah’s diagram of the scholastic interscope for how humans think.

0615 The following is a hybridization of terms from the S&T noumenal overlay and features from that scholastic interscope.

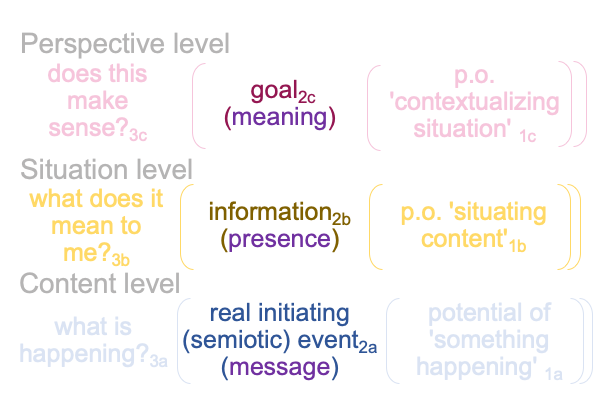

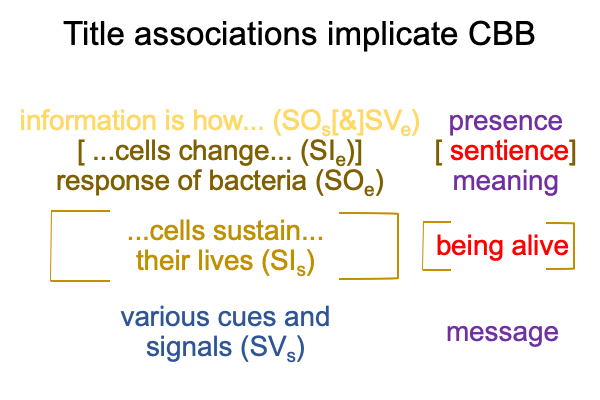

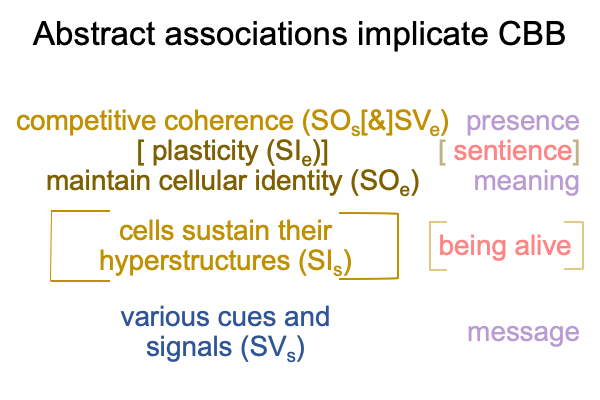

0616 At this point, the authors’ language-manipulations become more obvious.

Their title is “the sentient cell”.

The aim of their chapter is to model the cellular basis for consciousness.

And, right away, this examination associates the key titular terms to the sign-interpretants in Sharov and Tonnessen’s noumenal overlay.

Yes, these sign-interpretants contain subagents.

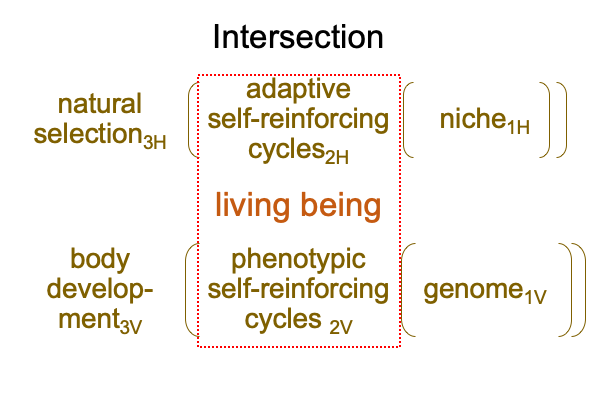

0617 The authors claim that life and sentience are coterminous (section 13.1 and 2).

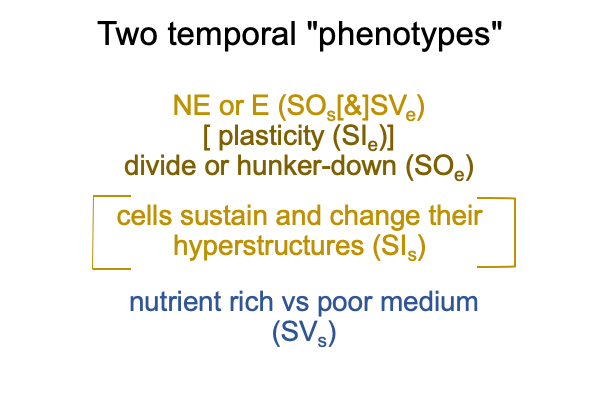

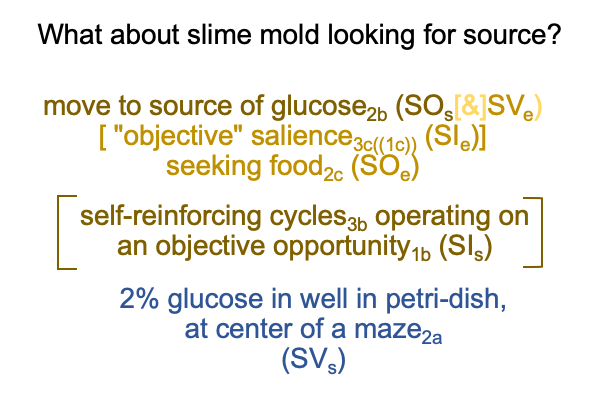

Then (section 13.2.1), they assert that unicellular organisms have sensory and perceptual mechanisms (SIs). They learn and remember (SIs and SIe). They make decisions (SIe).

0618 Then (section 13.2.2), the authors explore how biomarkers play roles among these sign-interpretants. These biomarkers include the actions (SOe(?)) by one subagent that serve as real initiating semiotic events (SVs) for another subagent. One subagent sends a message. The other subagent receives it. A biomarker released from one subagent provides information to another subagent. This information contributes to a goal that, for all practical purposes, both subagents have in common.

0619 At this point (section 13.2.3), the authors explicitly mention the term, “information”.

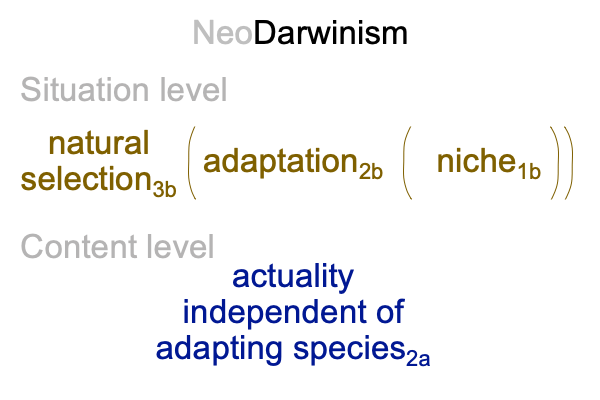

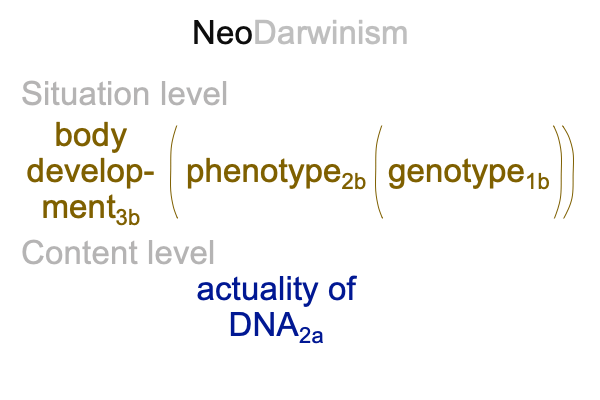

They note that biological information, unlike “information” in the computer sciences, is ambiguous. Why? The computer sciences focus on the transmission of information. The biological sciences are curious how information2b(SVe) stands for a goal2c (SOe) with respect to making sense3c (or, should I say, “sentience”) enough to take action1c(SIe). They also wonder how a real initiating event2b (SVs) stands for information2b (SOs) in regards to the living cell3b facing possible courses of action1b (SIs).

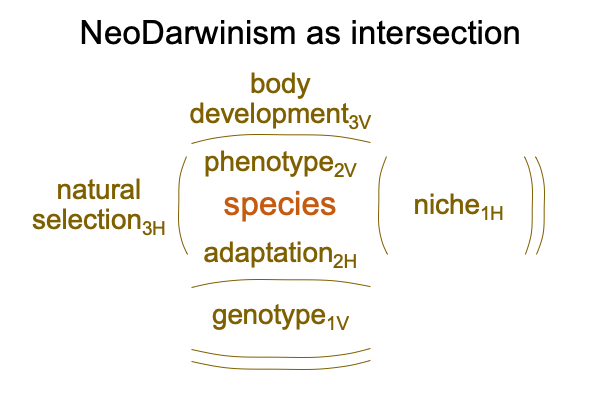

0620 In section 13.2.4, the authors insist that life and sentience cannot be attributed only to phenotypic expression of the cell. Yes, DNA allows reproduction to unfold from a template. But, the genome does not define the nature of biological agency.

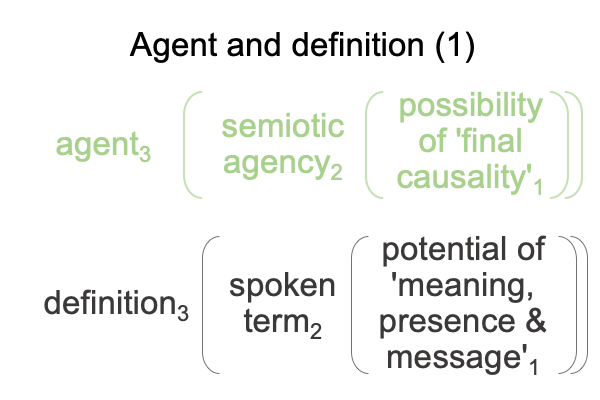

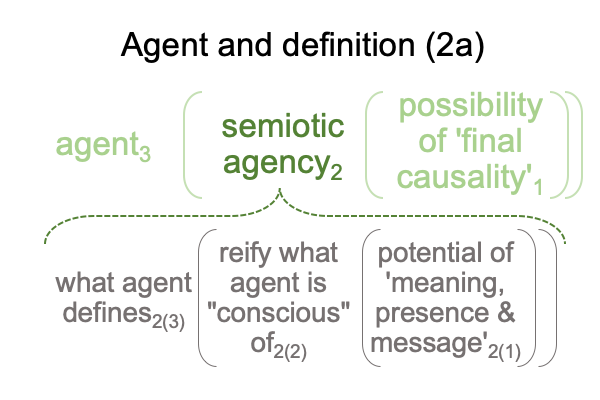

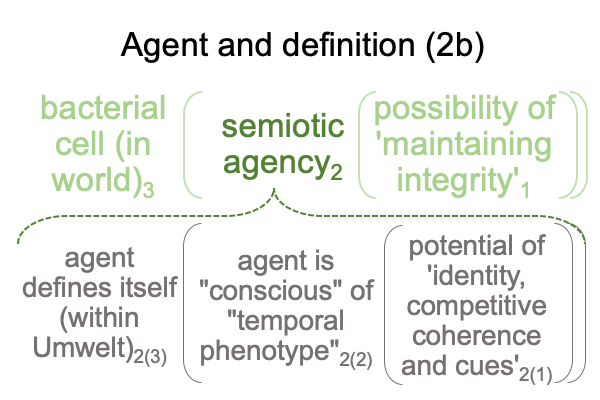

What defines semiotic agency?

0621 May I compare the category-based nested forms for agent3 and definition3?

Perhaps, such a comparison would assist in addressing the question, “If a sentient cell is conscious… or is conscious by analogy to human consciousness… then what is the sentient cell conscious of?”

0622 Surely, the sentient cell is not conscious of its own membrane.

But, it would be if it were conscious.

The cellular membrane is precisely what is needed for both life and sentience. So, the cellular membrane is a prime subagent. It is a foundational subagent. It is… so to speak… ground floor for both life and consciousness. Along with a host of other subagents, the cellular membrane gives rise to sentience, but it is not conscious of itself.

0623 Does that answer the question?

If life and sentience associates to sign-interpretants, then what the cell is conscious of must associate to the respective sign-vehicles and sign-objects.

How obvious is that?